Derek Turner’s Sea Changes

Jon Harrison Sims, American Renaissance, November 28, 2012

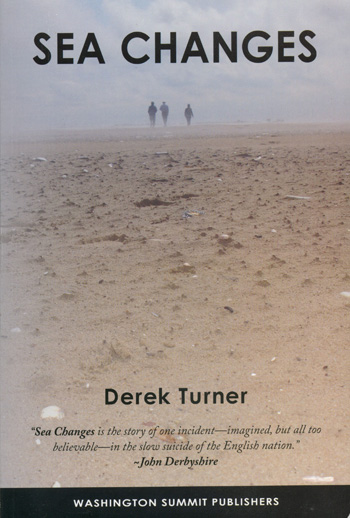

Derek Turner, Sea Changes, Washington Summit Publishers, 2012, 436 pp.

This is a political novel about immigration and the forces of political betrayal that make it a threat to the West.

There have been some very good political novels over the past 200 years, and they fall into four broad categories: Novels about revolution and the wars that often follow them (Joseph Conrad, Boris Pasternak, Graham Greene, Stendahl). Novels about terrorism (Fyodor Dostoevsky, Conrad again, G.K. Chesterton). Novels of a dystopian future (Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Ray Bradbury, Anthony Burgess, Jean Raspail). And fourth, novels about the political present, usually seen as demented or deranged in some way (Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry James, Wyndham Lewis). To this last category belongs Derek Turner’s excellent book about the multicultural degeneracy of the West.

I draw these distinctions only because many readers will compare Sea Changes to Jean Raspail’s Camp of the Saints (1973) because of the similarity of the theme: desperate Third-World refugees coming ashore in a Europe that lacks the will to throw them back. The difference is that Mr. Raspail’s tale of ships overloaded with South Asians arriving off the southern coast of France is set in the future, while Mr. Turner’s tale about migrants washing up dead on an East Anglian beach is set in the present. In other words, the events in Sea Changes did not happen, but similar things happen all the time. Mr. Raspail’s future dystopia has become our reality.

One reviewer, John Derbyshire, said the novel is about “one incident — imagined, but all too believable — in the slow suicide of the English nation.” It is suicide rather than murder because it is the English rulers and their media allies who are offering themselves up — or rather their people up — as a sacrifice to the gods of multiculturalism. The traitors themselves are sacrificing nothing, at least in the short term. They continue to enjoy power, celebrity, privileges, high salaries, a luxurious lifestyle, and of course the plaudits of the Left.

Mr. Turner tells his story on two separate tracks that slowly converge and meet. It opens on a summer morning when a local farmer, Dan Gowt, discovers dead bodies, all of them non-white, washed up on a beach near his home. Many have been shot as well as drowned. This instantly becomes a major media event and an occasion for leftwing posturing. When Gowt makes an “insensitive” comment to a television reporter about the migrants being “aliens,” “trying to sneak into the country illegally,” and that the English are in no way to blame for it, he becomes a target of leftwing abuse and a sort of celebrity ogre. His ordeal forms one story within the larger narrative.

A second English story unfolds as two columnists spar over the meaning of the incident and Gowt’s traditionalist views. One columnist defends him and the other attacks him, and Gowt’s only friend in the press also becomes a target of leftwing persecution.

The other track begins outside the city of Basra in southern Iraq, where a young Iraqi man, Ibraham Nassouf, has decided to go to England where he imagines his life will be better. Saddam is still in power, the sanctions are pressing, and British jets are patrolling the southern no-fly zone. A bored Nassouf looks up at the “foreign jets hurtling over, like falcons flashing from fantastic realms.” He is not angry at the white pilots flying over and bombing his land. He is awed by them, and wants to live in their country. He also longs for a pretty, fair-skinned, English wife. Ibraham, in short, has no national or racial pride, nor is he very religious. He may be Muslim, but his dreams are altogether carnal.

Mr. Turner has here brilliantly captured the psychology of many, perhaps most,Third World immigrants. It is not freedom that drives them but envy and greed. They want what the white people of the West have.

What’s worse, they think they are entitled to it. Why? For decades, they have seen or heard of educated people from their nation moving to the West, and enjoying the good life. They have also heard of poor people, perhaps members of their family, making it to the West, where they are housed and get medical treatment paid for by charities or the government. Some have been deported, but many more have stayed. Nassouf is told over and over that if he manages to get to the West his chances of being deported are slim.

The second story thus begins: the westward journey of Mr. Nassouf. Mr. Turner has clearly researched how Third-World migrants sneak into Europe. It is remarkably easy — if sometimes dangerous. All the migrant needs are dollars or Euros. He will find people all along the way willing — for a bribe or a fee — to help him get to the promised land. There is a virtual underground railroad by sea and by land for smuggling Africans, Arabs, and South Asians into Europe.

Nassouf, for example, begins by walking west across the desert into Jordan, where he jumps a northbound train for Turkey. Reaching a Turkish port, he pays a ship captain who, for $1,500, will land him on the shore of a Greek island. Greece, because it is close to Turkey and has thousands of miles of shoreline and hundreds of islands, is a major entry point for illegals.

The Greek government is obligated under international law to house and feed Nassouf, and to process his application for asylum. He has no grounds to request asylum, and he knows it. He had a job in Iraq, and was never persecuted. However, he is prepared to lie about his past, and he throws away his identity papers so as to make his lies harder to detect. This is standard procedure for illegal immigrants.

Nassouf is flown to an asylum centre on the Greek mainland, close to Athens, where hundreds of migrants from Africa and Asia wait for their asylum applications to be processed. After a few weeks of unrelieved boredom, the detainees riot. Nassouf takes advantage of the chaos to escape to the nearby town of Lavrion and its foreign ghetto, where he finds an Iraqi shop keeper who puts him in touch with Albanian human traffickers. They handle two types of cargo: white sex slaves and Third-World immigrants.

For $1,700, the Albanians will drive Nassouf and 11 others north in a truck to Rotterdam and put them on a boat to England. Nassouf and 41 others are to be put ashore on a quiet part of the English coast. The plan is foiled by a British fishery patrol vessel which spots them well offshore. The Albanians order the migrants into the sea. When they hesitate, the Albanians shoot them and throw the bodies overboard. Nassouf is the only survivor.

In England, the incident becomes a progressive cause célèbre. The multicultural Left says this tragedy would never have happened if England had open borders. The drownings prove “the evils of exclusion.” Lefties even accuse locals of shooting “the immigrants” on the beach, and they target Gowt as a symbol of “rural racism.”

A London reporter and columnist, John Leyden, visits Gowt and pretends to be understanding. He coaxes out more “anti-immigrant” comments, such as Gowt’s belief that foreign migrants should be repatriated. He then writes a column showcasing Gowt as an example of the kind of regressive and exclusionary ethnic attitudes typical of rural England. Gowt begins receiving threatening phone calls, and the harassment culminates in a terrifying incident in which a group of leftwing thugs smash his front windows in the middle of the night and paint “RACIST SCUM LIVES HERE” on his front door.

As Mr. Turner knows, the multi-ethnic Left in England is far more intolerant and far more violent than the nativists and “fascists” they claim to be fighting. Mr. Turner also knows that if a Muslim family in rural England had been the target of nativist vandalism, the press would have made it a national story, and the government would have sent in Scotland Yard.

But Gowt is on his own. The police respond to his wife’s call for help, but tell him that the chances of catching the perpetrators are next to nil, and seem generally unconcerned. When Gowt presses them for action, they warn him that he’s lucky that his “provocative comments have not been made the subject of a formal investigation.” As he tries to smother his rage, he wonders what has happened to his country.

Gowt has only two public supporters. One is James Fulford, chairman of the National Union, the political vehicle of English patriotism, but Gowt foolishly declines his offer of help, claiming that “he has no interest in politics.” Mr. Turner here has made a brilliant point, which is the reluctance of most whites to understand that they need to organize to defend themselves. They do not understand that a growing, anti-white coalition is dedicated to the dispossession of their people.

Gowt’s other defender is the venerable and iconoclastic columnist for the Sentinel newspaper, Albert Norman, whose regular Broadside column is one of the most popular features of the paper. Norman is one of Mr. Turner’s most brilliant characters, and reminds this reviewer of the late Joe Sobran. Norman is well-read in the classics and despises all forms of cant. He also seems to be the only journalist in the country with the courage and clout to challenge the dominant leftwing view of the “tragedy.” He writes a column blaming the drowings on the government for encouraging illegal entry by its lax immigration policies and reluctance to deport. He writes a second column defending Gowt’s traditional views, as well as his right to privacy. He notes that Gowt is just a farmer. He did not thrust himself into public view; he was pulled in by journalists.

The “anti-racism” crusade immediately sets about trying to get Albert Norman fired, and that becomes Mr. Turner’s third story line. The leftist columnist Leyden begins an editorial duel with Norman. Although Norman is a favorite among longtime readers, the Sentinel’s young editor — whom we know as only “Dougie” — begins pressuring him to tone down his columns. When Norman refuses, his column is buried in the back of the paper, and he is reassigned to a small office near the noisy advertising department.

To demonstrate its sensitivity, the Sentinel starts publishing a Nigerian-born ethnic activist, and prints a bright multi-racial advertisement featuring an attractive young blonde woman staring rapturously into the eyes of a grinning black man as they stand in a sunny field of flowers. The caption reads, “Isn’t it time you got together with someone spesh?”

An organization called No Borders Now! is planning a noisy demonstration with whistles and drums outside the offices of the Sentinel in downtown London. They advertise it as a mass protest “against media racism.” This is an insightful point by Mr. Turner about the organized Left’s image of itself as an embattled minority fighting a racist establishment. Norman does not represent the establishment at all. He is the only journalist in the country willing to defend Gowt and call for Mr. Nassouf’s deportation. Yet, for leftists, even one dissenter is too many; they are determined to silence him. The Left, as Paul Gottfried has observed, whether socialistic or multicultural, is always totalitarian. That is its nature. It is liberal only when it is out of power.

The Sentinel is owned by a politically correct conglomerate that fears controversy and will certainly replace the editor if he doesn’t take the heat off the paper. So when Dougie hears that a violent, militant group called “Freedom from Fascism” may join the demonstration, he begins to fear for his job. He panics completely when he learns that the National Union is planning a counter-demonstration to support Albert Norman and freedom of the press. It would be intolerable for the paper to appear to be on the same side as the right-wing National Union, so he delivers an ultimatum to Norman: write a placating column or be fired.

Norman reluctantly agrees, but it makes no difference. The demonstration takes place anyway, and Freedom from Fascism lives up to its thuggish reputation. It outwits the police and breaks into the offices of the Sentinel, while others attack and critically injure a hapless journalist whom they mistake for Norman. Albert Norman resigns the next day. The Left has won.

The Left’s other goal is to “keep Ibraham in England.” By law, Nassouf should be deported, as even the leftist Prime Minister thinks privately, but the government does not have the courage to do it, even after a television team investigates his story of persecution in Iraq discovers that it’s all a lie. The Left wins again. The Left’s third victory comes when the English Parliament votes to ban the anti-immigration National Union from holding political office at any level.

Our last glimpse of Nassouf is of a dejected and lonely man. He has no job, no English girlfriend, and is living in an overcrowded refugee apartment building in London’s grey slums. He begins to resent the English for not having met his desires. This reviewer suspects Nassouf might rediscover his Islamic faith as a vehicle for expressing his frustration, and become a terrorist.

Is Sea Changes a success or a failure? This reviewer was depressed by its emphasis on the masochism and meekness of Western peoples today. It leaves the reader with no hope that whites can ever recover their pride and courage.

That is not to say that it is a not a good novel or that it serves no purpose. It is a painfully acute diagnosis of Western cowardice and treason. One reviewer compares it to Stendhal’s best satire. Another praises its realism: “At last. A novel that reflects the world we actually live in!” Of course, the many favorable reviews are by people who agree with Mr. Turner. Everyone else is predictably ignoring it.

Those who read Sea Changes will no doubt be filled with a deep revulsion for the Left and a realization that no dialogue or compromise is possible. The ultimate impression left by Sea Changes is that England needs a new Arthur to drive the invaders and their collaborators into the sea.