A Re-Evaluation of the Life, Politics, and Philosophy of Enoch Powell

Jon Harrison Sims, American Renaissance, March 7, 2014

Lord Howard of Rising (Editor), Enoch at 100: A Re-Evaluation of the Life, Politics, and Philosophy of Enoch Powell, Biteback Publishing, 2012; 320 pp.

The 20th century was surely the worst century in the history of Europe. Whites killed millions of each other in two dysgenic, intra-racial wars that destroyed the continent’s confidence. One consequence was the loss of empires and colonial backwash: the migration of former subjects to white nations in Europe, North America, and Australia.

The population of England, for example, is today more than ten percent non-European. Fifty years ago, it was less than one percent non-white. England’s leaders introduced unassimilable minorities into their country, many of whom are hostile to Western institutions and culture. How did this happen?

Enoch Powell, who would have been 100 years old in 2012 when this book was published, was a Member of Parliament from 1950 to 1987 — just as these changes were taking place. Unlike most of his colleagues, he publicly opposed immigration and saw very early where it would lead. Ordinary Britons overwhelmingly supported him, but he was punished by his own Conservative Party. Enoch at 100 is a collection of essays on Powell’s career and politics. The contributors are contemporary commentators and political figures, and are generally sympathetic to Mr. Powell. The collection does not fully answer the question raised above, but it does make it clear who was to blame for this national betrayal.

John Enoch Powell (1912–1998) was not an ordinary politician. He was a brilliant classical scholar and linguist, who could read and write Latin and Greek, speak fluent French and German, and read medieval Welsh. In a Greek examination when he was a student at Cambridge, he translated passages from Bede’s 8th-century History of England into not just one but two styles of Greek, those of Plato and Thucydides — in half the time allotted for the test. In his late 20s, he wrote or edited scholarly works on Thucydides and Herodotus that are still read today. When the British declared war on Germany in 1939, Powell left his position as a professor of Greek at the University of Sydney in Australia, and joined his Majesty’s forces, where he served as an intelligence officer and rose through the ranks to become a brigadier general.

After the war, he went into politics — partly, he said, to help preserve the Empire — and was elected Tory MP for Wolver-Hampton South-West in 1950. He would represent the same constituency until 1974, when he left the Conservative Party in protest against Britain’s political and economic integration in Europe. He joined the Ulster Unionists and was elected as a Unionist MP that same year.

Non-white immigration into Britain began after the Second World War, mainly from colonies and former colonies in the Caribbean and South Asia. As Britain granted its colonies independence in the 1950s and 1960s, immigration paradoxically increased. Caribbean blacks, Pakistanis, and East Indians agitated for national independence, but after they won it, many decided they would rather live as a racial and cultural minority in a historically white country than in their own land governed by their own people. Powell opposed immigration as early as 1946.

The people of England shared Powell’s opposition to colonization by former subjects. In 1955, West Bromwich bus drivers went on strike to protest a Sikh driver who wore a beard and turban in violation of local regulations. Bowing to popular pressure, the city council sacked the driver, and Powell publicly praised the drivers for acting in defense of their country. However, the council faced withering media criticism and soon re-instituted the Sikh. Powell was outraged. A tiny minority of Sikhs, together with allies in the media, had gotten their way in the face of overwhelming community opposition. He believed this boded ill for the future, and it increased his opposition to non-white immigration.

Jun. 6, 1963 – Enoch Powell (Credit Image: © Keystone Press Agency / ZUMA Wire)

Mr. Powell understood the real reason for the bus drivers’ strike. They did not want Indian Sikhs settling in their country. The drivers, he said, “apprehended the dangers for the country of any appreciable coloured population being domiciled here.” By refusing to adapt to English norms, the Sikhs were making themselves even more conspicuous than they already were. Powell warned that “any readily visible differences between human beings inevitably result in political frictions.” Every attempt at multi-racialism continues to prove him right.

In the mid-1960s, nearly 75,000 non-white immigrants were entering Britain legally every year, and opposition to the influx was a winning political issue. In the constituency next door to Powell’s, a Conservative challenged the sitting Labour MP, Patrick Gordon Walker, in 1964, and ran on opposition to immigration. The Labour Party was pro-immigration, but it preferred to keep the issue out of politics and off the front page because they knew it was unpopular. Walker, who would have been appointed Foreign Secretary, lost to his challenger, and Labour cried “racism.” Powell, who had campaigned for the Tory candidate, told journalists that non-European immigration was going to become Britain’s biggest political issue.

The next year, 1965, Powell was appointed shadow Defense Secretary. Now in the leadership, he began urging the Tories to make immigration a national issue by calling for drastic reductions, and even a total ban. Powell argued that immigrants were straining hospitals and schools in his constituency, and were preventing cultural integration by those who had come earlier. The Conservative Party leader, Alec Douglas-Home, was sympathetic, and asked Mr. Powell to write a speech for him advocating reduced numbers and government-funded repatriation of recent immigrants.

Mr. Powell also accused the Labour government of deceiving the public on the number of immigrants. Ministers would tell journalists that only 7,000 entry permits were issued each year, but failed to mention that this meant more than 50,000 dependents were let in along with the permit holders. Powell publicized this deception in a February 1967 editorial in the London Telegraph. In 1968, as entry permits rose to 8,500, Powell gave a speech in the town of Walsall in which he said that allowing immigrants to bring in family relations was “crazy; enough to make one weep and drive one to despair.” The speech was widely reported and not all papers were hostile. Mr. Powell was becoming a national figure.

By this time, the Conservative Party had a new leader, Edward Heath, who disliked Powell’s outspokenness on immigration, and asked him not to repeat the arguments of his Walsall speech. Why? Perhaps he feared Powell as a rival. He knew that Powell’s support for a ban on immigration was popular. If Heath adopted the same policy, he would be seen as following Powell’s lead, and Conservatives might think Powell should lead the party. It is also possible that Heath was a coward on race, but political correctness was not as powerful, nor was the press so monolithic as today.

A new issue, however, was making the immigration debate even more urgent. Newly independent black governments in East Africa were preparing to expel up to 250,000 South Asians. Some claimed that the Asians of Kenya and Uganda had been promised British passports in 1962 by the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan. Powell argued that there had been no such promise, and that Britain had no moral obligation to a quarter of a million people who were not in any real sense British. The Labour government and senior Conservative leaders argued otherwise, and all the expelled Asians who wanted to move to Britain were let in.

And so, in April 1968, just two months after his Walsall speech, Powell again spoke about immigration before a Conservative political meeting in Birmingham. It would prove to be the most famous speech (full text here) by a British leader since Winston Churchill’s “iron curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri, in 1946.

He began by stating a political maxim he had learned from his classical studies: “The supreme function of statesmanship is to provide against preventable evils.”

As he pointed out, politicians in a parliamentary democracy are most concerned with being re-elected and retaining their majority. This means they focus on the short-term and avoid controversial or difficult issues, because they excite opposition. Politicians therefore postpone difficult decisions and ignore preventable evils precisely when they are most preventable. Powell was determined to make his colleagues face the reality of what their government was doing, and frighten them into taking action, even though it would be “just that kind of action which is hardest for politicians to take, action where the difficulties lie in the present but the evils to be prevented or minimized lie several parliaments ahead.”

The evil that Powell wanted to prevent was the introduction of an “alien element” into the British population that would continue to increase, unless stopped, until it would reach 10 percent of the population by 2000. Powell predicted 3.5 million immigrants and their descendants by the mid-1980s and five to seven million by 2000. He did not explain what made these immigrants alien: race, religion, culture, and history.

May 5, 1968 (Credit Image: © Keystone Press Agency/ZUMA Wire)

Officials and journalists denounced Powell’s estimates as hysterical exaggerations. David Ennels of the Home Office minister called them “sheer fantasy.” Two demographers assured Britain that what Powell was predicting “won’t happen.” Richard Crossman, a Labour minister, called his predictions “untrue, alarmist, and totally irresponsible.” Yet Crossman confided to his diary that he pressured government statisticians to doctor the numbers so as to undercut Powell’s projections. Even Powell’s fellow Tories preferred to pretend that what would surely happen unless the Parliament acted would not happen.

Needless to say, Powell’s estimates were accurate. Britain’s African and Asian populations alone were 4.5 million in 2000. Including Arabs, Iranians, Turks, and others whom the British government called white put the real number well within Powell’s estimate of five to seven million. By 2010, Britain’s non-white population had increased to 9.1 million.

Powell knew that in 1968 most of Britain was largely untouched by immigration. He represented one of the few constituencies with a large and increasing foreign presence. He therefore recounted the unsettling experiences of his English constituents who found themselves “strangers in their own country.” This was what would happen to all of England if MPs did not act.

Powell also predicted that immigrants would agitate for special privileges. He mentioned the Race Relations Bill, which was being debated in Parliament, and would forbid “discrimination” in housing, employment, and public services. Powell foresaw that such a law would amount to protected status for non-whites. He predicted — correctly — that it would encourage non-whites “to agitate and campaign against their fellow citizens, and to overawe and dominate the rest with the legal weapons which the ignorant and the ill-informed have provided.”

The most famous parts of Powell’s speech were his two classical allusions. The first was:

Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependents, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.

He also quoted from the Aeneid, in which the prophetess Sybil tells Aeneas that he must expect to fight for his new home in central Italy: “I see wars, horrible wars, and the Tiber foaming with much blood.”

Here is how Powell used the quotation:

As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood.’ That tragic and intractable phenomenon [racial conflict, sometimes violent] which we watch with horror on the other side of the Atlantic but which there is interwoven with the history and existence of the States itself, is coming upon us here by our own volition and our own neglect. Indeed, it has all but come. In numerical terms, it will be of American proportions long before the end of the century. Only resolute and urgent action will avert it even now.

He added that not to take action in 1968 would constitute “betrayal” and would call down “the curses of those who come after.”

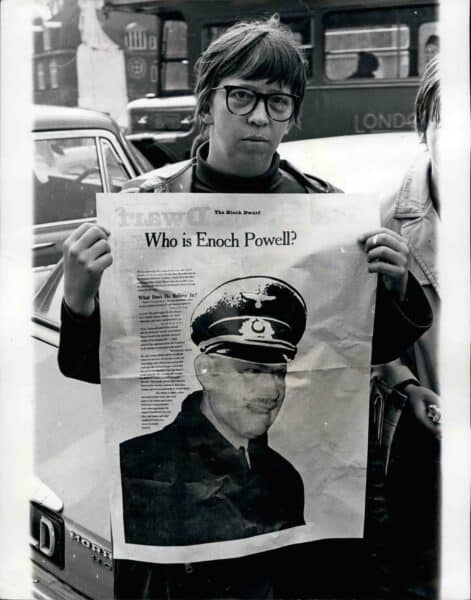

The reaction to Powell’s speech was divided between popular favor and elite disdain. The London Times, a supposedly conservative paper, called it “an evil speech,” “disgraceful,” “shameful,” “a deliberate appeal to racial hatred.” Even Edward Heath, the Conservative leader, called it “racialist in tone and liable to exacerbate racial tensions.” (Of course, importing large numbers of non-whites was the best way to exacerbate racial tensions.) Heath sacked Powell as shadow Defense Minister, explaining that his speech was “unacceptable from one of the leaders of the Conservative Party.”

Powell himself received 100,000 letters of support, and only 800 in protest. The Tory rank and file were furious at Heath for removing Powell. Thirty-nine immigration officers at Heathrow airport wrote to him, saying, “We are fed up with the corruption and deceit that goes on to get immigrants into this country.”

Even the working class, who overwhelmingly voted Labour, demonstrated in solidarity. Some 4,000 London dockworkers went on strike to support him, and a group of 800 marched on Westminster singing “I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas” — though it was not Christmas time, and “Bye Bye Blackbird.” On the way, they were joined by the Smithfield meat porters and others. Labour MPs who denounced Powell were shocked when they were booed by their own working-class voters.

Support for Powell was so strong that Heath had to scramble to appease it. He did not re-instate him as shadow Defense Minister, but did concede that immigration should be “severely curtailed” and repatriation encouraged. Even the openly pro-immigration Labour government announced that entry permits would be cut from 7,500 to 5,000 a year.

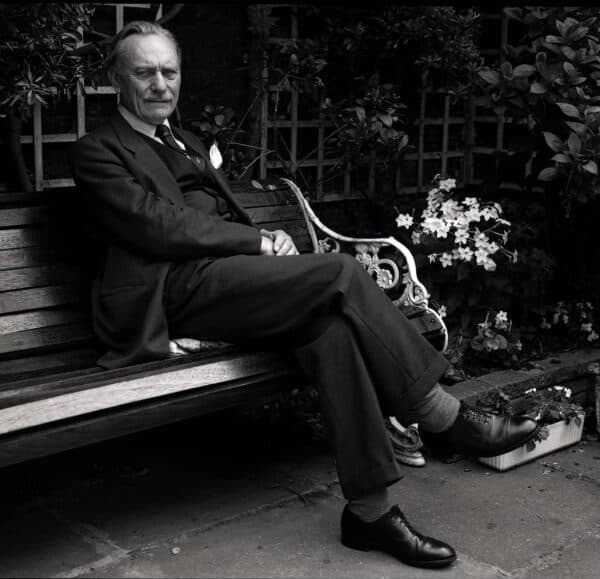

Enoch Powell (Credit Image: Allan Warren via Wikimedia)

In the next general election in 1970, Powell was re-elected by the largest margin of his career, and the Conservative Party won a majority in the House of Commons. Subsequent analysis suggests that Powell’s speech increased the Conservative vote by 1.5 percent, which was enough to turn a Labour majority of 25 into a Conservative majority of 30.

Conservative leaders denied that immigration had helped them win, and took their turn at lying about it. The party’s election manifesto had promised “no further large-scale permanent immigration,” but by September 1971, 180,000 new immigrants had arrived in Britain. In the first year of Edward Heath’s term as Prime Minister, annual immigration increased by 17 percent.

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s Powell continued to speak out against immigration but the media mostly ignored him and the Tories avoided the issue. But why didn’t the Conservative Party cut immigration? This would have won over the base of the Labour Party, and the Tories could have governed uncontested for at least a generation. Why did they run away from the issue?

Powell touched on this in 1987, his last year in Parliament, when he spoke of “the almost unlimited capacity of my fellow countrymen for self-delusion:”

Anyone would have been dismissed as raving mad who in 1950 told the people of Britain that by the end of the century approaching one-third of the population of inner London and of certain other areas of England would be negro or Asiatic. [Today, the percentage for inner London is nearly double that of 1987.] It was by drawing attention to that prospect more than a decade and a half later that I was to alter the course of my own political life and arguably the course of British politics. Yet, for all that, if a voice from heaven had told me in 1950 that Britain would do such a thing to itself, I would have found the prophecy horrific but not incomprehensible.

Why “not incomprehensible”? Powell suggested that the British people were traumatized by the rapid loss of their overseas empire and the status as a great power that went with it. But that does not really answer the question. And there was no doubting the power of the anti-racial ideology that paralyzed Edward Heath but did not daunt Powell.

A painting of Enoch Powell, by Ruskin Spear, entitled ”Study Against a Black Background” (Credit Image: © Keystone Press Agency / ZUMA Wire)

Britain was lucky to have a man who could defend her so lyrically. In a 1961 speech on nationality, he spoke about “the unity of England, effortless and unconstrained” and went on to praise what he called:

. . . the homogeneity of England, so profound and embracing that the counties and the regions make it a hobby to discover their differences and assert their peculiarities. The continuity of England, which has brought this unity and homogeneity about by the slow alchemy of ages. . . . From this continuous life of an united people in its island home spring, as from the soil of England, all that is peculiar in the gifts and the achievements of the English nation, its laws, its literature, its freedom, its self-discipline.”

Certainly, no one today would say such things about England. It is a tragedy that the nation that produced such a loyal and loving son has disappeared forever.

Readers of Enoch at 100 will find contributions by Nicholas True on Powell and the European Union; Frank Field on Powell’s parliamentary career; Michael Forsyth on Powell and the British Constitution; Simon Heffer on Powell on the government and the economy; Roger Scruton on Powell and the English language; Andrew Roberts on Powell’s English nationalism; Tom Bower on Powell and immigration; Andrew Alexander on Powell’s foreign policy views; Margaret Mountford on Powell’s classicism; and Alistair Cooke on Powell and Northern Ireland.

These essays are interesting, but it is Powell’s own words that are most rewarding. There are eight of his speeches — including, of course, his most famous — as well as a few of his poems and a delightful interview with his widow. Needless to say, Powell spoke and wrote on many more subjects besides immigration, and his arguments are always precise and well stated. He was so deeply versed in parliamentary traditions that his speeches are an education in how the British government works.

Powell’s views were scorned, and his deepest hopes for his country dashed, but this book proves that he survives in a way that other politicians do not. Certainly no one reads Edward Heath’s speeches anymore.