The Truth About Black Soldiers in The Great War

Robert Hampton, American Renaissance, June 16, 2022

Americans are constantly reminded of alleged black valor. Historians love to cite the 54th Massachusetts, the Harlem Hellfighters, and the Tuskegee Airmen to prove the value of the black soldier. Popular movies such as Glory and Red Tails promote the myth. Schools then spread it.

In the politically incorrect past, the army did not believe the myth. In a 1925 report, it declared the black man a poor soldier.

“Employment of Negro Man Power in War,” published by the Army War College, described the performance of black troops in the First World War. Its conclusion: “The negro, particularly the officer, failed in the World War.” The report notes also that blacks were only one percent of combat casualties even though blacks were roughly 10 percent of the US population.

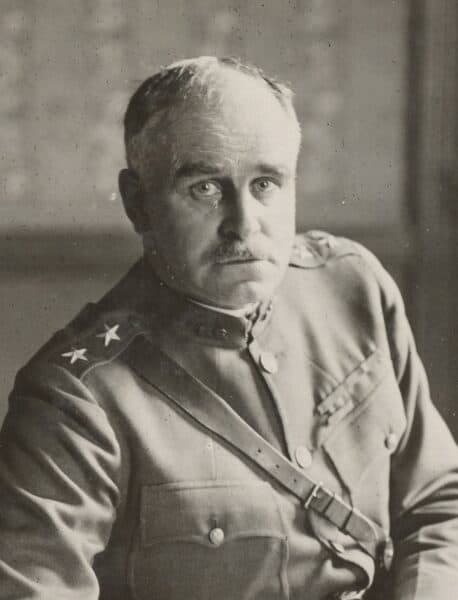

The author was Maj. Gen. Hanson Edward Ely, commandant of the Army War College, and he saw the Great War firsthand. He earned the Silver Star, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army Distinguished Service Medal, the French Legion of Honour and five Croix de Guerres. By the end of the war, he commanded the Fifth Infantry Division. Ely knew how the war was fought and had a first-rate military mind.

Maj. Gen. Hanson E. Ely

Here were his views:

The negro is physically qualified for combat duty.

He is by nature subservient and believes himself inferior to the white man.

He is most susceptible to the influence of crowd psychology.

He cannot control himself in the fear of danger to the extent the white man can.

He has not the initiative nor the resourcefulness of the white man.

He is mentally inferior to the white man.

The report does not recommend that America should exclude blacks from military service. The Army should use them mainly for labor, keep them separate from white units, and require that their few combat units be led by white officers. A central conclusion is that blacks have “not developed leadership qualities.”

Ely’s report offers a thorough analysis of “the physical, mental, moral, and psychological characteristics of the negro.” The report found that a lower percentage of blacks were rejected from service due to physical handicaps than whites, but this was not because of black physical superiority; it was because of lower induction standards for blacks. The high command found many black draftees physically unfit for combat due to overlooked ailments and greater susceptibility to disease. The analysis also found that Southern blacks were particularly lazy.

The mental capacity of blacks was rated very low. This was not based on anecdotes or field reports but on intelligence tests administered by the Army, which ranked soldiers from D- to A. Forty-nine percent of black soldiers fell into the D- category while only 0.1 percent were in the A category. By comparison, just 7 percent of white soldiers were D- while 4.1 percent were A. More than 3 percent of black officers were D- and 14.7 percent were A. Only 0.1 percent of white officers were D- while 49.2 percent were A.

351st Field Artillery troops on the deck of the Louisville en route to the United States after the end of WWI.

“As judged by white standards, the negro is unmoral,” notes the report. “Petty thieving, lying, and promiscuity are much more common among negros than among whites.” The report also claims blacks commit “atrocities” against white women and “that the negro will protect his color in cases of emergency without regard to truth.”

The report says many black patrol reports were unreliable, that black officers would mostly kill time on night patrols and come back with nothing to report. Studies found that the black soldier displayed intense resentment towards whites, but this was “numbed by his easy going nature.” The commanding officer of a regiment in the 92nd Division declared that the black officer “has not the fine points of honor that should characterize the American Army officer.” The report worries that the “negro’s growing sense of importance will make them more and more of a problem, and racial troubles may be expected to increase.” There were several race riots following World War I, which suggest that black military service increased unrest.

The report finds that the ordinary black was very superstitious, which made him afraid of ghosts and omens. This made him a “rank coward in the dark.” The black soldier was said to give way to fear under less pressure and to be more susceptible to crowd psychology than the white soldier: “He simply cannot control himself in fear of some danger in the degree the white man can.” The report also claims that blacks did “not see that certain things are wrong.” It concludes that “the psychology of the negro, based on heredity derived from mediocre African ancestors, cultivated by several generations of slavery, followed by about three generations of evolution from slavery in the anomalous state of legal without actual equality with the white, is one from which we cannot expect to draw leadership material.”

The report surveyed the performance of black units in the war. The 368th Regiment performed especially poorly. It was one of the few black units to go into combat, but it failed to achieve its goal, was badly demoralized after coming under fire, and retreated without orders to do so. The high command blamed the black officers, 35 of whom were removed from service for inefficiency and cowardice. Five were court-martialed and convicted. The commander of the French division under which the regiment fought declared the unit useless for combat.

Officers of the 366th Infantry Regiment, circa 1918.

The report does compliment the combat performance of the 93rd Division, but notes that most of its officers were white, which the War College credits for its superior performance. Still, the 93rd was inferior to white American and French counterparts.

The survey reviews the past military service of black Americans and finds it insignificant. No full unit of blacks was ever raised in the Revolutionary War and the few black units that served in the Civil War and Indian Wars were led, with a few exceptions, by white officers and noncoms.

The War College’s report is largely forgotten — and it’s obvious why. It undermines liberal myths about blacks and American history. It is a story of blacks shirking their duty and fleeing the field. The report is from a time when American officers were race realists, unafraid of inconvenient truths.

Today, the military makes soldiers learn Critical Race Theory and purges alleged “white nationalists.” Which is likely to be the more effective fighting force?