Fighting Back Against Your Liberal College

Kristina Saxon, American Renaissance, January 1996

Temple Law School has seen better days. Today the campus is entirely surrounded by North Philadelphia slums. Armed robberies, assaults, and car thefts are common. Last spring, several locals murdered a white undergraduate who was withdrawing money from an automated teller machine in broad daylight.

The university administration downplays the danger. It thinks it is being reassuring when it reminds students that the campus police force ranks fourth in size in the entire state of Pennsylvania — just behind the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh police departments.

There have been violent students as well. Temple Law School has admitted a convicted murderer who served time in prison. It also admitted a “homeless person,” and actually let him live in the law library. One morning the homeless man woke up and choked a law student who had walked into his sleeping room to use a computer. The two were wrestling on the floor when police arrived. The school refused to expel the attacker, saying that he probably suffered from “Vietnam Syndrome.”

Several years ago, a black janitor at the law school stabbed someone with a screwdriver and then went back to work. A witness said he was dumping trash when the police arrived. It has been reported that the dean of the law school, Robert Reinstein, served as a character witness for the janitor, asking the city prosecutor for leniency.

What happens, though, when a white, notoriously conservative student defends himself against a black attacker? The same dean of the law school, Robert Reinstein, throws him off campus, calling him “a clear and present danger.” The story and its aftermath are a dismal reminder of the political and racial climate on American campuses, but there is always hope — for those who are willing to fight back.

Clear and Present (Political) Danger

In 1993, Lincoln Herbert, a third-year student at Temple Law School, founded a student organization called the Western Heritage Society (WHS), which sponsored a program of lunch-hour lectures. Among the speakers were syndicated columnist Samuel Francis, American Renaissance editor Jared Taylor, and author Lawrence Auster. Prof. Linda Gottfredson, who has done pioneering work on race and IQ, was a speaker, as was Raymond Wolters, author of The Burden of Brown.

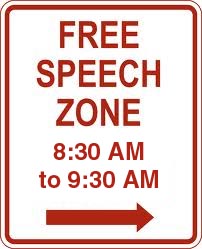

Mr. Herbert advertised the lectures on bright red, 11” × 17” posters on which he reproduced political cartoons and wrote provocative essays about the subjects of the lectures. He also wrote a spirited column called Notes From the First World for the law school newsletter. He inveighed against “sodomites,” “MTV jungle music,” “white guilt,” “speech codes,” and the “cult of multiculturalism,” claiming that most law students, especially the liberals, were as brainwashed as the “American sheeple.”

On one poster, advertising a lecture about affirmative action, he wrote, “Are there not striking parallels between the techniques of thought control in Huxley’s [brave new] world and those of the propagandists of Affirmative Action . . . ? How better to wheedle majority America into acquiescence to their own economic, cultural, and political dispossession than by making Inherited Guilt the new religion?”

Almost single-handedly, Mr. Herbert battled the political orthodoxy that otherwise silences dissent at Temple University. His mix of provocation and populism kept the administration, faculty, and liberal students in an almost constant uproar. At one point, alarmed liberals proposed an emergency Student Bar Association resolution, which would have disqualified the Western Heritage Society from receiving its share of university funding that is available to all other organizations, regardless of political view. It failed by just one vote, 19 to 18.

Things came to a head in April, 1994, when Mr. Herbert won the “David Horowitz Student Activism Award” at Harvard University from the National Association of Scholars. He exultantly publicized the award with his trade-mark red posters. Two days later, Dean Reinstein wrote a personal “Letter to the Law School community,” sharply attacking Mr. Herbert and the WHS for their “message of hatred and vitriol.” The letter was posted all over the Law School (even over men’s room urinals) and then published in the student newsletter. Mr. Herbert was denied the opportunity to publish a reply.

About two weeks later, a black campus trespasser accosted Mr. Herbert, demanded money, pursued him into the law school, and shouted threats at him. The man claimed to have a knife and threatened to use it. Mr. Herbert had been a victim of street crime on three previous occasions since enrolling at Temple Law School, and had started carrying pepper gas. When the man rushed toward him inside the law school, Mr. Herbert sprayed him. Campus police arrived, restrained the spluttering man, and took him away in handcuffs. Mr. Herbert gave the officers a full statement, went home, and thought no more of the incident.

Two days later, Dean Reinstein called Mr. Herbert into his office and handed him a letter suspending him from the law school for two and a half years. The letter did not even accuse Mr. Herbert of violating school regulations. Dean Reinstein wrote that he thought Mr. Herbert’s account of the black man’s threatening behavior was “fabricated,” and pronounced him “a clear and present danger to the safety of the law school community.” Mr. Herbert asked if he might shut the door to the office and talk privately. “No, leave it open,” replied the dean; “you’re dangerous.” The dean had the astonished student escorted off campus by an armed guard. Dean Reinstein warned him that if he returned to campus he would be prosecuted for “criminal trespass.”

Ordinarily, such an act of political intimidation might have gone unchallenged, but Mr. Herbert filed a $6,000,000 law suit in federal court contesting the suspension. In October of this year, 17 months after the suspension — and five months after Mr. Herbert would have graduated had he not been suspended — a three-judge panel concluded that Dean Reinstein had not followed procedural due process in suspending Mr. Herbert. The dean, a former civil rights lawyer, had violated the student’s civil rights. In November, the U.S. Court of Appeals rejected the dean’s motion that the October decision be overturned.

This, however, is only a very partial victory. The dean should not have suspended Mr. Herbert when he did, but the court left the school’s later conduct untouched. The law school’s disciplinary committee eventually suspended Mr. Herbert officially and ordered him to undergo a psychiatric evaluation. These decisions, taken after Mr. Herbert filed suit, must be the subject of yet more litigation — which will be expensive.

In its ruling, the appeals court intimated that the pepper gas incident was a pretext for punishing someone the law school had other reasons to dislike. Mr. Herbert, if not an actual political prisoner, is certainly a victim of political persecution.