How the White Ethnics Assimilated

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, April 2006

David Roediger, Working Towards Whiteness: How Americas Immigrants Became White, Basic Books, 2005, 339 pp.

It is now required of liberal academics that they at least claim to believe race is not a biological category but a sociological delusion. To the extent they really believe this, it makes it hard for them to write about racial consciousness or racial attitudes. Virtually all of American history becomes a puzzle to them because, from the very beginning, it has been driven by a mass delusion that afflicted everyone from the founders down to the average white man of today.

Working Towards Whiteness is full of interesting information about how turn-of-the-century immigrants fit into American racial etiquette, but it suffers badly from the obligatory inability to understand race. Thus, David Roediger, chairman of the history department at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, writes irritatingly about “the making of race,” of the “racialization of immigrants,” or about the “racialized neighborhoods” in which blacks live — as if the ghettos would have been tidy, middle-class suburbs if whites had not “racialized” them. Somehow, generation after generation, Americans “invented” race and forced each other into meaningless categories.

As the title of his book indicates, the equally meaningless problem Prof. Roediger tries to solve is how the 13 million “new immigrants” who came from Eastern and Southern Europe between 1886 and 1935 ended up being “racialized” as white. Later we shall see what prevents Prof. Roediger from seeing the obvious: they were treated as white because they were white.

Race and Ethnicity

During the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, Americans used the word “race” more loosely than we do today. Not only did people talk about the African and Asian races but also the English and French races. As Prof. Roediger notes, they often used odd, half-biological, half-cultural phrases like “the English-speaking races.” The expression “white ethnics,” he writes, did not become widespread until after the Second World War, and the most common designation for turn-of-the-century non-Nordics was “new immigrants,” which distinguished them from the Britons, Germans, and even the Irish who came earlier.

There is no doubt that the newcomers were different from the old stock. H.G. Wells worried in The Future of America (1906) that by welcoming the “darker-haired, darker-eyed, uneducated proletariat from central and eastern Europe” the country would develop “another dreadful separation of class and kind.” Prof. Roediger quotes a character from Sinclair Lewiss Babbit:“These Dagoes and Hunkies” would have “to learn that this is a white man’s country, and they ain’t wanted here.” This kind of loose usage is pretext enough for anyone who really wants to believe that the old stock did not realize Italians and Slavs were white.

And, indeed, there seems to have been a strong sense that Sicilians and southern Italians in particular were very alien, and if the pioneer stock ever did question whether some “new immigrants” were non-white, it was the dark-skinned ones who set them wondering. Prof. Roediger notes that one of the standard pejoratives for Italians — “Guinea” — comes from a term that was originally used for Africans, either to indicate which part of the continent they were from or to distinguish African-born from American-born slaves. Later, “Guineas” were mostly Italians but could be dark-skinned Greeks, Jews, Portuguese, or Spaniards. The old stock clearly did not care for them.

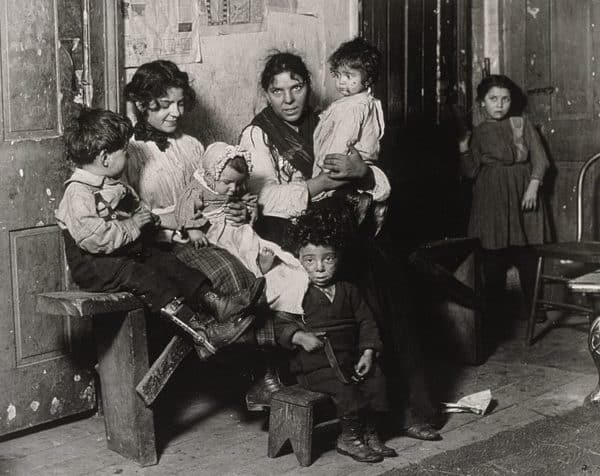

Italian-Americans in the early 1900s. (Credit Image: Lewis Wickes Hine via Wikimedia)

In 1915, Irish dock workers left their jobs rather than work with “Guineas,” and as late as the 1960s, Italians were trying to get the word Guinea removed from place names. Jack London once wrote that “Dagoes and Japs” were the real enemies of Anglo-Saxon America. Socialist leader Eugene Debs said in 1891 that the Italian “fattens on garbage” and lives “far more like a wild beast than the Chinese.” One early 20th century novel referred to grand opera as “a bunch of greasers [singing] a lot of Dago stuff.”

“Italian” was, in some cases, a polite term for any dark-skinned person. The one black family that went down on the Titanic was lost to history for many years because it was described as “Italian” on the passenger manifest — as were several Japanese.

In some parts of the South, Sicilians were considered a very low breed. An Italian government worker investigating sharecroppers in Louisiana reportedly had a hard time persuading plantation owners that Sicilians were white. Southerners thought of them as a kind of light-skinned Negro who worked harder than the dark-skinned ones. Prof. Roediger reports that on a few occasions, Southern schools assigned swarthy Italian children to the black school rather than the white school. One 1922 Alabama anti-miscegenation prosecution led to a curious acquittal: The white offender, an Italian, was determined not to be “conclusively white,” so no offense could have taken place. Even in the North, some employers considered Italians to be the least desirable workers. Prof. Roediger cites an 1896 advertisement for “common labor” that offered the following daily pay: “white $1.30 to $1.50 . . . colored $1.25 to $1.40 [and] Italian $1.15 to $1.25.”

Needless to say, Italians themselves distinguished between light and dark. Northern Italians have long held that Africa begins at Naples, and parents used to tell their children to stop being Africani when they misbehaved. Even now, the Italian Lega Nord (Northern League) campaigns for political separation from the south.

Umberto Bossi, founder of the Lega Nord, at the party’s first rally in Pontida, 1990. (Credit Image: Maxperot via Wikimedia)

There is no evidence that Slavs and what the Nordicists called the “Alpines” were ever treated quite like Sicilians. They ended up in the catch-all “Hunky” (from Hungarian) or “Bohunk” (from both Hungarian and Bohemian) category, and had a reputation as strong, dedicated, but rather stupid laborers. One steel worker explained to an industry investigator that “only Hunkies” worked at blast furnace jobs, because they were “too damn dirty and too damn hot for a white man.” In 1908, when a plant manager in Steelton, Pennsylvania, offered to move skilled “white” men to “Hunky” work, the men walked off the job.

Edward Alsworth Ross (1866-1951), perhaps the foremost American sociologist of his time, wrote that the new immigrants were “the product of serfdom” and the opposite of the “typical American citizen whose forefathers have erected our democracy.” He added that Slavs were “immune to certain kinds of dirt” and “can stand what would kill a white man.”

In some mining operations in the West, new immigrants were kept out of the white mens camps, as were Mexicans and Asians. At some sites, Italians had to share quarters with Mexicans.

Does all this mean, as Prof. Roediger suggests, that the old stock did not think the new immigrants were white? The language, religion, appearance, and bathing habits of the newcomers combined to make them alien and even repulsive, but sending a few Sicilians to black schools hardly meant people in the South thought they were actually Negroes. Protestants of British stock did not want to mix with short, dark Catholics, and it was convenient to park them in black schools, and the abortive 1922 anti-miscegenation prosecution is at best a historical curiosity.

As even Prof. Roediger himself recognizes, naturalization laws throughout this period specified that citizenship was open to “free white persons,” and no one ever argued that “Guineas” and “Bohunks” were unqualified. Other races were. In 1922, the Supreme Court ruled that Japanese could not naturalize because they were not white. The next year, a subcontinental Indian came before the court, claiming he was “Caucasian,” and therefore eligible. In earlier cases, the court had sought expert testimony from anthropologists as to who was white, but in the Thind case, the justices ruled that it was simple common sense not to consider Indians white. New immigrants from Europe were unfailingly admitted to citizenship.

The census bureau during this period counted new immigrants the same way. It classified the first generation and their children as “foreign-born white,” but counted the third generation simply as white. This reflected both scholarly and popular assumptions. As a 1932 study by Donald Young called American Minority People noted of the new immigrant, it was “dimly realized that in a few generations he will be absorbed into the total white population.” Young went on to say that the “white immigrant [is] patently handicapped by foreign language and tradition” but the “Negro now is looked on as more of a biological problem.”

The prominent sociologist Henry Pratt Fairchild (1880–1956), whom the author calls “racist” for his views of non-whites, took a haughty but different view of the southern or central European: “If he proves himself a man and . . . acquires wealth and cleans himself up — very well, we might receive him in a generation or two. But at present he is far beneath us and the burden of proof rests with him.” Unlettered aliens would have to prove they could become American, and as Prof. Roediger notes, even the Italians found that if they renounced their foreign habits they were accepted. By 1920, scholars were generally predicting that European ethnics would assimilate. They were making no such predictions about blacks.

Henry Pratt Fairchild

Labor Unions

Prof. Roediger goes into considerable detail about how labor unions treated the new immigrants. The American Federation of Labor did not like them, and some of its leaders wondered “how much more immigration can this country absorb and retain its homogeneity?” In 1902, AFL leader Samuel Gompers approved of literacy tests for immigrants because they would “shut out a considerable number of Slavs and other[s] equally or more undesirable and injurious.” One steel plant union man asked, “How would you like to shake hands with niggers and foreigners, and call them brothers?”

Nevertheless, unions that were firmly closed to blacks were almost always open to white ethnics. In 1905, an Irish labor leader conceded, “However it may go against the grain, we must admit that common interest and brotherhood must include the Polack and the Sheeny.” Some unions drew the line at accepting non-citizens. Prof. Roediger reports that in the 1930s, one third of all members belonged to unions that excluded foreigners. Virtually all kept out blacks, as Samuel Gompers put it, as a matter of “self-preservation.” The CIO, on the other hand, had an anti-racist element that tried to organize around the slogan “negro and white, unite and fight,” but with little success. The Jewish-led International Ladies Garment Workers Union tried interracial organizing but newly-arrived Jewish immigrants in New York sharply resisted making common cause with people they called schwartzes.

The color line was always far more impermeable than the nationality line. In 1944, 1,500 UAW members went on strike because a new work arrangement required black and white women to use the same toilet. Prof. Roediger notes there could be union trouble if the coat racks were arranged so that blacks coats touched those of whites.

Housing patterns were another area in which new immigrants were clearly treated as whites and not like blacks or Mexicans. Before the Second World War, the “ghetto” was where new immigrants lived after arrival, but from an early period, ethnic concentration was voluntary. Unlike blacks, the Italians and Poles could move freely into old-stock neighborhoods and many did. New immigrants took pride in their communities, however, often showing higher rates of home-ownership than other whites. Social workers noted that they would buy a house “even if they have to starve their families to get the money,” and wondered if this were an extension of the peasant hunger for land. Blacks were different; the Negro quarter was often a wreck.

Catholic ethnics frequently showed their love of community by building splendid churches, and Prof. Roediger writes that the clergy often joined in efforts to keep out Negroes. When blacks arrived in the 1960s, the bitterest part of white flight for many ethnics was turning their backs on the magnificent churches they had helped build.

Prof. Roediger gives an interesting history of restrictive covenants that likewise shows how smoothly new immigrants were “racialized” as white. In 1890, courts struck down covenants designed to keep out Asians, and they were banned again in 1917, on the grounds that they limited the rights of whites to sell property to whomever they wanted. However, they spread very rapidly after a 1926 Supreme Court decision found them constitutional.

It was not always a simple matter to institute covenants. Usually at least 70 percent of owners had to agree to them — no one wanted to be the only one to limit his resale rights — and it took organizing effort to get people in line. Covenants often expired after a number of years and had to be voted back onto deeds. This also took organizing, usually by groups known as neighborhood improvement associations. Many associations did nothing other than push covenants; keeping out non-whites was the single best step toward “neighborhood improvement.”

Prof. Roediger concedes that white ethnics were almost never kept out by covenant, and notes that even the early regulations of the Federal Housing Authority encouraged homogeneous neighborhoods. The realtors code of ethics likewise forbade sales to buyers who would hurt property values. “Guineas” and “Hunkies” did not hurt property values, and glided easily into covenanted housing. Prof. Roediger idiotically calls this “coerced incorporation as whites,” complaining that “new immigrant populations were poorly situated to enter multiracial initiatives” — as if they had to be forcibly dragged out of cozy neighborhoods full of charming blacks.

White On Arrival

This is the sort of nonsense people write when they pretend to believe race is an accidental designation that could easily go either way. For trendy loonies, therefore, it has become an academic problem to speculate about the manner and timing of how new immigrants were anointed as whites rather than something else. The thinking seems to be that in the home country they would have had no idea of race, and became “racialized” only in America. As Prof. Roediger explains: “U.S. realities were brutal, effective teachers of racial division and immigrants were ready learners.” In The American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal complained that race prejudice was “one of the lessons in Americanization.” Theoretically, if they hadnt been trained to “racism” by the old stock, new immigrants would have met blacks and American Indians and Japanese and not even noticed. In “racialized” America they were forced to notice, and found themselves designated “white on arrival,” a concept Prof. Roediger finds so useful and significant he abbreviates it WOA.

The following paragraph from Working Toward Whiteness is worth studying:

A possible reading of the WOA characterization would be that new immigrants were white before coming (WBC) and therefore carried racism in the cultural baggage that they brought across the Atlantic. Recent scholarship rightly taken up with the drama of immigrants learning the ‘lie of whiteness’ in the United States, has been slow to consider this possibility.

If race is a delusion, there has to be some explanation for why so many people are deluded. The fashionable view is that Americans are actively recruited into the “lie of whiteness.” Prof. Roediger is offering the shocking possibility that new immigrants might actually have been white (and therefore “racist”) before they got to America — “white before coming!” He quickly backs away from this heresy, however, and insists that new immigrants must have learned “racism” after they got here: “Much more difficult to interpret,” he writes, “are immigrant sources reporting on early encounters with African Americans,” who found blacks to be “utterly beyond imagination in European frames of reference.”

One Pole wrote home saying, “If such a man were brought to your village then all people would run away from fear.” A Slovak woman going through Ellis Island screamed when a black porter took her bag. She thought he was a monkey. In Clevelands Little Italy, a woman who saw a black in the street for the first time ran home in a fright, shouting “Madonna Mia mi scanza” (“My Lady protect me”). There was a standard immigration story among Italians of meeting their first black and thinking the color could surely be washed off.

Why does Prof. Roediger find these accounts “difficult to interpret”? Because he insists on at least pretending to believe race is an illusion to which people succumb only after they have been “racialized.” Only a deluded academic could fail to understand the astonishment of a white person, before the era of television and press photography, meeting his first African. The brute fact of physical differences was a profound shock — and runs both ways. Even today, in remote African villages seldom visited by whites, children run away screaming when they see one. Poles and Slovaks may never have thought about race before they came to America, but once they clapped eyes on an African they understood it immediately. They didn’t have to wait for malevolent old-stock Americans to “racialize” them.

In fact, many Europeans did not live in a homogeneous, raceless world. Prof. Roediger concedes that nearly every European country had an underclass, whether it be gypsies, Jews, Slavs or Sicilians. W.E.B. Du Bois, the light-skinned American black, was often scorned as a gypsy or Jew when he traveled in Europe. Germans in America did not invent schwartze as a pejorative for blacks; the word came from Germany, where Ashkenazi Jews sometimes used it for Sephardic Jews as well as blacks. To his credit, Prof. Roediger concedes that the issue of “racialization” is a “messy” one, and that some people don’t seem to require much instruction in telling races apart (though he doesn’t mention it, infants can do it).

Confusion

The main problem for trendy academics is the belief that race is not biological but there is at least one other problem. They are confused by the fact that old-stock Americans disliked the new immigrants. Anti-racists like Prof. Roediger do not seem to realize that there is an infinity of reasons for looking down on people even of one’s own race. The old stock disliked the people coming down the gangways because they were illiterate, badly-dressed, spoke no English, stank of garlic, and professed strange religions — not because anyone thought they were not white. An Englishman who behaved like a Dago was not welcome in boardrooms or even living rooms either. Anti-racists are so obsessed with “racism” they can think of no other reason to make Italians bunk with Mexicans in mining camps.

In the end, it was entirely as Henry Fairchild had suggested: once the Sheenies and Bohunks made a little money, dressed properly, learned English and acquired good manners, they could go anywhere. It might take a generation or two, but the outcome was essentially preordained. New immigrants were not “working towards whiteness.” They were leaving behind their European peasant origins and becoming middle-class Americans. Only Ph.Ds stuffed with fashionable nonsense could be blind to the obvious.