Revealed: One in Four Europeans Vote Populist

Paul Lewis, Seán Clarke, Caelainn Barr, Josh Holder and Niko Kommenda, The Guardian, November 20, 2018

Populist parties have more than tripled their support in Europe in the last 20 years, securing enough votes to put their leaders into government posts in 11 countries and challenging the established political order across the continent.

The steady growth in support for European populist parties, particularly on the right, is revealed in a groundbreaking analysis of their performance in national elections in 31 European countries over two decades, conducted by the Guardian in conjunction with more than 30 leading political scientists.

Overall populist vote share in Europe, 1998 to 2018

Combined vote share by year for 31 countries, as at last parliamentary election

The data shows that populism has been consistently on the rise since at least 1998. Two decades ago, populist parties were largely a marginal force, accounting for just 7% of votes across the continent; in the most recent national elections, one in four votes cast was for a populist party.

“Not so long ago populism was a phenomenon of the political fringes,” said Matthijs Rooduijn, a political sociologist at the University of Amsterdam, who led the research project.

“Today it has become increasingly mainstream: some of the most significant recent political developments like the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump cannot be understood without taking into account the rise of populism.

“The breeding ground for populism has become increasingly fertile, and populist parties are ever more capable of reaping the rewards.”

Supporters of populism say it champions the ordinary person against vested interests and hence is a vital force in any democracy. But critics say that populists in power often subvert democratic norms, whether by undermining the media and judiciary or by trampling minority rights.

The findings of the study come six months before European parliamentary elections that some are predicting could return more rightwing populists than ever to the 751-seat chamber.

It reveals the different fortunes of rightwing populists such Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Italy’s Matteo Salvini, who have had the most success in recent years, and leftwing populist parties, which rapidly expanded in the aftermath of the financial crisis but failed to secure a seat in government anywhere other than Greece.

In order to track the success of populist parties in Europe, Rooduijn and the Guardian worked with political scholars to examine hundreds of political parties and decide whether or not they were populist at different stages over the past 20 years.

National election results since 1998 were then mapped on to the party definitions to show trends over time.

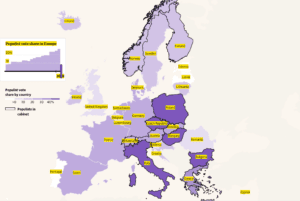

The map shows how populism flickered across the continent in the late 1990s before really catching on in eastern Europe throughout the 2000s. It spread north in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis before making substantial inroads in western Europe’s major powerhouses in the past three years.

Europe is not alone in experiencing this rise: populists have been elected to executive office in five of the world’s seven biggest democracies: India, the US, Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines.

Populism in Europe goes back several decades: the far-right Freedom party of Austria was founded in 1956 by a former Nazi and first won more than 20% of the vote in 1994. It is now part of the country’s ruling coalition.

Populist parties enjoyed success in Norway, Switzerland and Italy in the 1990s. But it was not until the turn of the century that populist ideas, legislators and challengers started to proliferate, from the Netherlands to France, Hungary to Poland.

Since then, anti-establishment populism has snowballed, particularly after the 2008 financial crash and the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe. The anti-austerity Syriza took 27% of the vote then 36% in successive Greek elections; Ukip propelled Britain to its Brexit vote and Marine Le Pen became the second member of her family to reach a presidential run-off in France, winning 33% of the vote.

The anti-immigration Alternative für Deutschland has become the first far-right party since the second world war to enter every German state parliament and holds more than 90 seats in the Bundestag; in Italy, the far-right League and anti-establishment Five Star Movement won nearly 50% of the popular vote; Fidesz has been returned in Hungary with 49% of the vote; and the far-right Sweden Democrats have advanced to 17.5%.

The research shows that leftwing populists, which in Europe are far less successful than their conservative counterparts, have begun increasing their share of the vote in national elections, giving rise to challenger parties such as Podemos in Spain and La France Insoumise.

“There are three main reasons for the sharp rise of populism in Europe,” said Cas Mudde, a professor in international affairs at the University of Georgia. “The great recession, which created a few strong left populist parties in the south, the so-called refugee crisis, which was a catalyst for right populists, and finally the transformation of non-populist parties into populist parties – notably Fidesz and Law and Justice [in Poland].”

Claudia Alvares, an associate professor at Lusofona University in Lisbon, who was not involved in the Guardian research project, said: “The success of such politicians has very much to do with their capacity to convince their audiences that they do not belong to the traditional political system. As such, they are on a par with the people to the extent that neither they nor the people belong to the ‘corrupt’ elites.”

She said social media had a role to play in the rise of populism, its algorithmic model rewarding and promoting adversarial messages. “The anger that populist politicians manage to channel is fuelled by social media posts, because social media are very permeable to the easy spread of emotion. The end result is a rise in the polarisation of political and journalistic discourse.”

While the overall trend in Europe shows a dramatic rise in populist vote share, the picture remains nuanced. In Belgium, for example, the populist Flemish nationalist party Vlaams Belang has been in decline for a decade. And populist parties that enter government – and are, of necessity, forced to compromise on their promises – can find life hard.

The Finns party, which joined Finland’s ruling coalition in 2015 after winning 17.5% of the vote, has imploded and split in two; its two successor parties are polling at 10% and 1.5%. In Greece, Syriza has slid to 25% from the 36% that swept it to power in 2015.

Support for the Danish People’s party, which lends support to a minority centre-right government, has fallen from 21% in 2015 to 17%. And Ukip’s popular backing has also fallen away spectacularly since Britain voted to leave the EU.

Continent-wide, however, the picture is unambiguous: 12.5 million Europeans lived in a country with at least one populist cabinet member in 1998; in 2018, that has risen more than tenfold, to 170.2 million.

As for the future, elections in the first half of 2019 will provide further scope to chart the rise and rise of populism, from Ukraine to Denmark, Finland to Belgium.

“In the short term, populist parties will probably stay roughly this strong, although they will be even more clearly radical right and there will remain significant regional and national differences,” said Mudde. “The main question is how non-populist parties are responding.”

[Editor’s Note: There are charts and other supporting materials with the original article.]