The Truth About Police Violence Against Black Men

Mark Tapson, Frontpage Mag, September 22, 2017

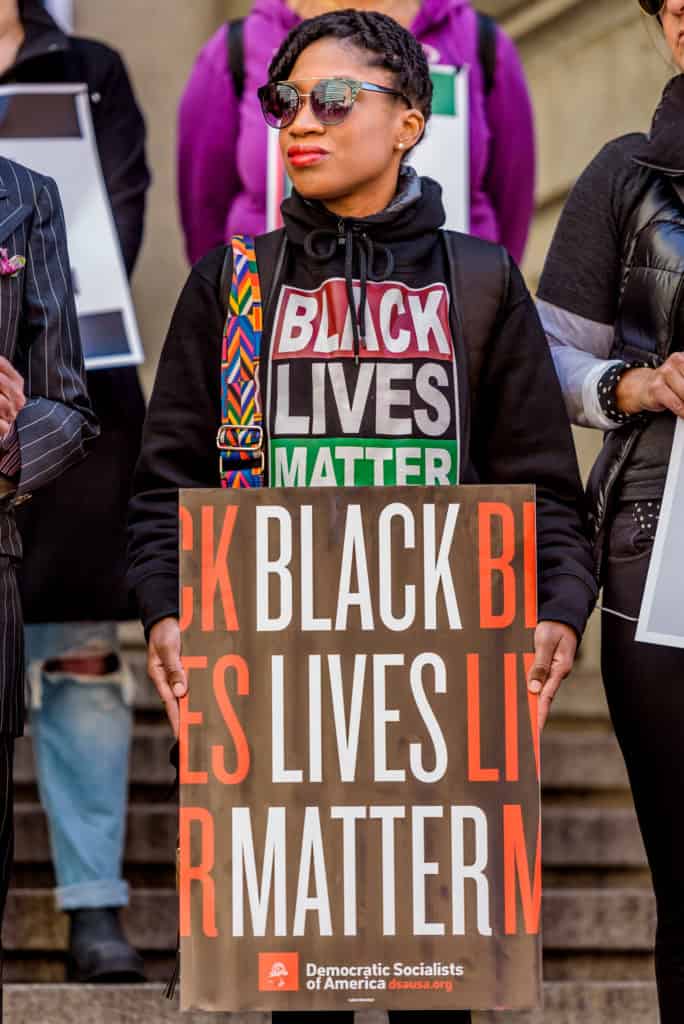

Credit Image: © Erik Mcgregor/Pacific Press via ZUMA Wire

In the wake of violent protests in St. Louis following the acquittal of white former police officer Jason Stockley for the murder of black suspect Anthony Lamar Smith, a Cornell University doctoral candidate in philosophy has put forth an argument you’re unlikely to hear in the mainstream media. Writing at National Review Online, Philippe Lemoine marshals actual facts and logic to demonstrate that, contrary to received wisdom, black males in the United States do not suffer a disproportionate degree of police brutality.

The largely undisputed narrative about cops and black men goes like this: black males are victimized daily all over America by police harassment and brutality, even when innocent, and there is an epidemic of police shootings of unarmed black men. This narrative is false, says Lemoine, and “distracts from far more serious problems that black Americans face.” Furthermore, the news media acceptance of it “poisons the relations between law enforcement and black communities throughout the country and results in violent protests that destroy property and sometimes even claim lives.”

The reality, Lemoine declares, is that a random black male is “overwhelmingly unlikely” to be the victim of police violence, and any disparity that does exist between the violence blacks and whites experience in their encounter with cops “is consistent with the racial gap in violent crime, suggesting that the role of racial bias is small.”

According to the Washington Post, just 16 unarmed black men out of a population of more than 20 million were killed by the police in 2016 – down from 36 the year before. These figures are numerically comparable to the number of black men that could be struck by lightning in any given year, Lemoine calculates, and they include cases in which the shooting was justified, even if the person killed was unarmed.

“Police killings of black unarmed males are incredibly rare, and it’s completely misleading to talk about an ‘epidemic of them,” he writes, pointing out that the left makes a similar comparison “when they argue that it’s completely irrational to fear that you might become a victim of terrorism.”

It’s not even true that black men are beaten on a regular basis by the police, or even pulled over constantly without reason. Using data from the Police-Public Contact Survey, based on a nationally representative sample of more than 70,000 U.S. residents age 16 or older, Lemoine notes that “black men are less likely than white men to have contact with the police in any given year.” Only 1.5 percent of black men have more than three contacts with the police in any given year, he points out – only marginally more than the 1.2 percent of white men who do.

Actual injuries by the police are so rare that they cannot even be estimated precisely, says Lemoine. “The data suggest that only 0.08 percent of black men are injured by the police each year, approximately the same rate as for white men. A black man is about 44 times as likely to suffer a traffic-related injury.” Again, these figures include instances in which violence is legally justified.

There does exist a racial disparity in the police use of physical force, but this experience is rare for men of all races. Only 0.6 percent of black men experience physical force by the police in any given year, states Lemoine, compared to approximately 0.2 percent of white men. Granted, that is three times as often; however, this disparity is less likely to be the result of racial bias, as people commonly assume, than the fact that black men commit violent crimes at much higher rates than white men do.

Citing data from the National Crime Victimization Survey, Lemoine notes,

that black men are three times as likely to commit violent crimes as white men. To the extent that cops are more likely to use force against people who commit violent crimes, which they surely are, this could easily explain the disparities we have observed in the rates at which the police use force. That’s not to say that bias plays no role; I’m sure it does play one. But it’s unlikely to explain a very large part of the discrepancy.

As for black Americans’ own perceptions of how they are mistreated by the police, Lemoine points out that individuals can be trusted about their own personal experiences, but “when it comes to larger social phenomena,” other factors come into play besides just their personal experience – the media, for example, which is very influential in terms of perpetuating the false narrative about police brutality against blacks. For example, most Americans believe that crime in the U.S. has increased since the 1990s, despite an abundance of information that crime has actually fallen dramatically. “[I]f people of any color can be wrong about this,” reasons Lemoine, “there is no reason to think black people can’t be wrong about the prevalence of police violence against minorities.”

His clear-eyed argument echoes the similarly fact-based presentation of Heather Mac Donald’s recent, essential read, The War on Cops: How the New Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe. That sobering book warns that an “academic victimology industry” and a complicit media have stoked Black Lives Matter hatred of the police and propelled the current “anti-cop narrative to powerful mainstream status.”

Facts may be stubborn things, as John Adams said, but facts alone are not especially effective against a deeply entrenched, cultural narrative protected and promoted by forces such as the media. Smashing that false perception of an epidemic of police violence against black men will take a combination of the facts with an emotionally powerful counter-narrative – and enough minds that are receptive to truth.

[Editor’s Note: Heather Mac Donald’s book The War on Cops, has been reviewed in AR. See here.]