The White Nation of Africa

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, July 2009

Hermann Giliomee, The Afrikaners: Biography of a People, University Press of Virginia, 2003, 698 pp.

Ten years in the making and drawing upon a bibliography of nearly a thousand sources, this epic history of the African continent’s sole white nation is not merely monumental, it is unavoidable; no other history of the Afrikaners (as opposed to general histories of South Africa) is available in English. The author is a professor of history at Stellenbosch University and already had a dozen books to his credit when this three-pound tome appeared. His American publisher is at pains to note that Prof. Giliomee was “one of the earliest and staunchest Afrikaner opponents of apartheid,” and his failure to consider racial differences requires the reader to supply his own interpretation of some of the events described. It is nevertheless a comprehensive treatment of a remarkable people.

The Dutch East India Company sponsored settlement of the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 with the idea of setting up a small and intensively cultivated colony whose sole purpose was to provision Dutch ships en route to and from Java. The seemingly inexhaustible land round about exerted too great a temptation, however, and within a few years settlers were farming and herding extensively in the surrounding countryside. With land plentiful and labor scarce, the company made the fateful decision to import slaves from the Dutch East Indies. Some writers (such as Arthur Kemp) believe white reliance on non-white labor was the fatal mistake that doomed South Africa from the start. Needless to say, Prof. Giliomee does not discuss that theory; instead, he emphasizes the hierarchical nature of the society that emerged and the chronic fear of gelykstelling — social leveling — that characterized the Afrikaners ever afterward.

Within a generation, whites were occupying land beyond the first mountain range and were effectively beyond company control. They quickly broke most of their attachments to Europe — with the important exception of the Reformed Calvinist faith — and began thinking of Africa as their only home. Settlers typically had East Indian slaves who spoke broken Dutch look after their children. As a result, later generations of whites inherited a simplified Dutch, somewhat analogous to Pidgin English (where “me go” replaces “I am going,” for example). This formed the basis of Afrikaans, an important badge of social identity in years to come.

The new nation was strengthened by the immigration of Germans and French Protestants: 20th century DNA studies revealed that not more than 40 percent of Afrikaner ancestry is Dutch. Meeting little resistance from the primitive native pastoralists they called Hottentots (now more often known as Khoi or KhoiKhoi), the nascent Afrikaner nation quickly spread eastwards along the coast for some 400 miles. In the late 1700s, in the “Zuurfeld” region between Algoa Bay and the Fish River, they encountered the tougher Xhosas, racially distinct from the Hottentots. For several decades, what Prof. Giliomee calls “the Eastern frontier cauldron” was an African counterpart to America’s Wild West.

In 1795 the British took control of the Cape and tried to impose their law and language on the Afrikaners, whom they regarded as cultural and moral inferiors. The British abolished slavery in 1834, and the Afrikaner frontiersmen feared complete gelykstelling might be in the offing.

So deep was their distrust of the British administration that in the 1830s several groups, without any central leadership, took the radical step of moving hundreds of miles into the interior in a migration known as the Great Trek. They founded two new republics: the Orange Free State and the Republic of South Africa, later known as the Transvaal.

Painting of the Great Trek

For a time, Britain recognized the independence of the Boer Republics, but when gold was discovered near Johannesburg, the British found pretexts for muscling in. The climax of this new British-Afrikaner conflict was the Boer War of 1899-1902. The British captured the Boer capitals by the spring of 1900 but a group known as bittereinders (“bitter-enders”) kept up a guerrilla campaign against the invaders for two more years. By May 1902, attrition had reduced them to fewer than 20,000, while the British had increased their forces to half a million. By the end of the war, 4,177 Boer women and 22,074 Boer children had died in British concentration camps. This history of irrational defiance in the face of overwhelming defeat — something American Southerners should easily recognize — is an important element of Afrikaner folk memory to this day.

Even this brief summary may give the reader some idea of what Boer War hero Jan Smuts meant when he said, “What young nation can boast a more romantic history, one of more far-reaching human interest? Color, incident, tragedy and comedy, defeat and victory, joy and sorrow . . . . If only we had the pen of the Greeks . . . !”

Hermann Giliomee, unfortunately, is no Herodotus. The Boers are clearly a colorful people, marked by that combination of independence and obstinacy that Americans used to call “cussedness.” Prof. Giliomee presents a wealth of information conscientiously, but lacks a novelist’s talent to bring his characters to life or let us see through their eyes.

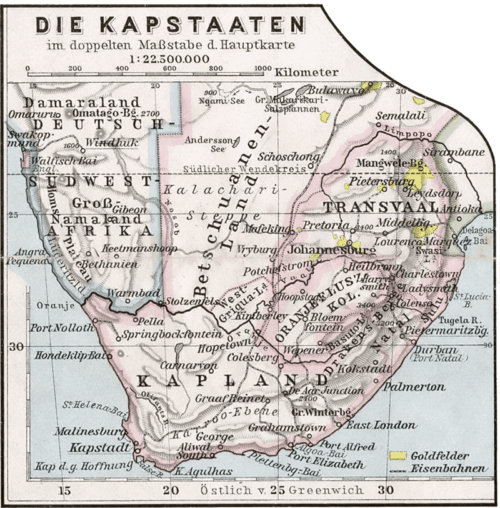

The author covers the two and a half centuries that end with the Boer War in 278 pages, leaving the bulk of the work — nearly 400 pages — for the last century. By 1910, the defeated Boer republics were integrated with the Cape Colony and Natal to form the Union of South Africa, with the borders it has retained to this day.

Although whites made up only about a fifth of the population, native resistance at first seemed less of a threat to civilization than the so-called poor-white problem, which was the most pressing political issue from the early 20th century until the 1940s. Afrikaners who could no longer support themselves on farms were streaming into the cities. They were illiterate, unskilled, and unwilling to work at wages blacks accepted. The 1925 replacement of Dutch by Afrikaans as South Africa’s co-official language with English was motivated in part by the need to educate these poor whites.

South Africa circa 1905

The purpose of early racial legislation was to guarantee whites employment at a “decent” wage by insulating them from competition with blacks. This was justified to liberal skeptics as a temporary measure that would let whites regain their footing and eventually benefit the black majority as well. Implausible or cynical as this may sound, it is more or less what happened. By the Second World War, dire white poverty was a thing of the past, and blacks and Coloreds assumed many of the menial jobs involved in wartime production.

In later years, as the wrath of non-whites and liberals focused on “apartheid,” a legend grew up that race relations had been relatively benign and were improving before the Nationalists came to power in 1948 and began to implement their racial policies. In fact, there had long been laws governing race relations — the British themselves introduced the pass system in the 19th century — and the wartime government of Jan Smuts laid some of the foundations of apartheid. It introduced compulsory voter registration for whites only, built all-colored suburbs, and required employers to segregate work and eating areas. Local authorities were already calling for an official national register classifying everyone by race, but segregation remained a ramshackle system of piecemeal responses to specific situations.

Even the liberals of the time heartily disapproved of miscegenation. They wanted the indefinite continuation of de facto residential and social segregation, but preferred social to legal sanctions, and envisioned the eventual removal of the color bar from the South African Constitution. The leading liberal in the United Party once admitted, however, that the assumption that social pressure could take the place of laws “calls for faith in no small degree,” and wondered whether “it will ensure the white man’s position in South Africa” and “make South Africa safe for European civilization.”

The Afrikaners of the Nationalist Party, who were painfully conscious of their weakness in numbers, were not prepared to take chances. Apartheid, or “separateness,” was to be a survival plan. It was born unobtrusively in Dutch Reformed Church circles in the 1930s as a mission strategy of working toward self-supporting and independent indigenous churches.

Political apartheid was a kind of secular generalization of this policy that took shape in the years before the successful 1948 elections. Its designers looked to the American South for guidance, and studied contemporary theories about conflict prevention in plural societies. Prof. Giliomee shows that, tendentious arguments of leftist historians notwithstanding, Nazi ideology had virtually no influence on apartheid. Nationalists were, in his words, “unequivocally rejecting National Socialism as an alien import into South Africa, and endorsing parliamentary democracy.”

Apartheid was based on reciprocity that was to guarantee its essential justice; whites were granting blacks everything they demanded for themselves: schools, churches, homelands and (eventually) governments, each operating in its own language. A crazy-quilt patchwork of Bantustans — reserved areas where whites were not allowed to purchase land — had been set up as early as 1913 and expanded in 1936. These areas were to be future independent homelands where the “original social order of the natives” would be re-established. The Afrikaners may have been projecting their resistance to British cultural and linguistic imperialism onto blacks, many of whom were happy to move to the cities, abandon their customs, and speak English.

The apartheid era was one of unprecedented prosperity for South Africa, and blacks shared in that prosperity. From 1960 to 1980 their average disposable personal income grew 84 percent, from Rand 1033 to 1903 (adjusted for inflation), and life expectancy rose from 38 years to over 60. The Nationalists spent more on education and medicine for blacks than previous governments.

According to the census of 1946, whites made up 21.6% of South Africa’s population, and demographers expected that figure to rise to 23.2% by the end of the century. To the consternation of demographers and the government, however, the black population grew rapidly — so rapidly that the average age of black South Africans fell to below 16. The white share of the population dropped steadily, to 17 percent in 1976 and 12 percent in 2000.

Black-white economic cooperation, which apartheid was careful not to interfere with, benefited both races, but by employing blacks in unpleasant jobs, whites were sowing dragons’ teeth. As the number of blacks increased, whites grew dependent on them. The Afrikaner nation that survived the Great Trek and the concentration camps of the Boer War finally capitulated to the effects of prosperity.

Says Prof. Giliomee: “Hendrik Verwoerd [the “architect of apartheid”] always believed that, confronted with a choice between being rich and integrated, and segregated and poor, the Afrikaners would choose the latter. But the strong surge of prosperity over which he presided tilted the scale heavily in favor of the former. Whites had become accustomed to economic growth producing steadily improved social circumstances and a comfortable lifestyle.”

A statue of Hendrik Verwoerd, the “architect of apartheid.”

According to one grim joke, white South Africans would rather be murdered in their own beds than make them.

Some early apartheid theorists had envisaged an eventual “total apartheid:” an all-white state coexisting with several black states, each with its own viable economy and separate labor force. In the early 1950s, Afrikaner leaders explicitly rejected this vision, and it gradually disappeared from public discussion. Somehow, the homelands were never developed. The truth is that South African whites could not bring themselves to do without cheap black labor.

Still, it was not inevitable that the Afrikaner nation would abandon its fate to the ANC. This catastrophe was brought about by the steady demoralization of whites, their will sapped by years of being treated as “the polecat of the world.” As Prof. Giliomee makes clear, the Afrikaners were never defeated; they simply surrendered.

We may never know why the whites of South Africa — both the English and the Afrikaners — voted in a 1992 referendum to rewrite the constitution. Whites still had virtually complete control of the country, and the voters probably never expected their leaders to give up so much so quickly. As Prof. Giliomee puts it, “That [President F. W.] de Klerk and his negotiators would manage to retain so little despite a position of relative strength places a serious question mark over his leadership abilities.” This judgment is particularly thought-provoking, coming as it does, from an opponent of apartheid.

ANC-ruled South Africa is a highly centralized state with no built-in guarantees for minorities. Its current system of organized looting known as Black Economic Empowerment is giving the new ruling class a powerful taste for wealth, which in a few more years will no longer be there to loot. What will stop South Africa eventually from driving out whites and destroying its economy as Zimbabwe has done?

Afrikaner history is an inspiring story of a European people very similar to America’s founding stock. For many generations Afrikaners cultivated the powerful racial and tribal consciousness necessary for survival in the midst of alien and hostile races. Softened by prosperity and demoralized by the disapproval of outsiders, they ceased to believe in themselves and surrendered without firing a shot. In the decades ahead, we other men of the West will find occasion to learn both from their virtues and from their terrible mistakes.