To the Ronin of the West

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, March 4, 2022

“My unorthodox thesis can be summarized in one sentence: Excising war from our historical horizon has led to the disappearance of virility from Western European societies.” So writes Dominique Venner in A Handbook for Dissidents. War has indeed returned to Europe. Europeans are killing each other in another Western civil war.

According to Vladimir Putin, Ukrainians and Russians are one people, but not part of the West. Ukrainian nationalists say they are fighting the foreign Russian occupier. According to countless press reports, “The West” is now confronting a non-Western power. Volunteers organizing on Reddit and other websites may be joining the largest pan-European military project since the Waffen-SS. Both sides say they are anti-fascists and that their foes are Nazis.

War has returned to the European consciousness and defense policy is suddenly being taken seriously. And though war is on our “horizon,” the Great Replacement is not. I see only two white peoples with below-fertility birth rates butchering each other.

A Ukrainian army soldier watches the smoke from shelling on March 4, 2022, in Irpin, Ukraine. (Credit Image: © Diego Herrera/Contacto via ZUMA Press)

Despite sympathy for Russia among some conservatives, “white nationalists” may be on the side of the Ukrainians. However, victory could lead to an “independent” Ukraine’s integration into the soulless, cultureless, decadent parody of European civilization that Dominque Venner gave his life to protest. “The current cosmopolitan system stems from Europe’s decline,” he wrote. “There is no commonality with our perennial civilization. The latter is to be sought elsewhere, in the best of what has been handed down to us.”

If Europe is to be changed, it must be changed from the center, and, I’m persuaded, by France. That is France’s new civilizing mission, though Venner certainly saw no contradiction in standing for France and Europe. “It is good to think and talk about Europe as a union of peoples in one civilization,” he advises young dissidents. Still, Venner’s subtitle, The Spiritual Testament of a Samurai of the West, shows uncertainty. Though Venner argues that Homer wrote the foundational poem of our civilization, he takes a “detour” through Japan better to understand our own tradition. The Japanese would not need a detour in order to understand themselves.

Venner may have called himself a “samurai” of the West, but without a master, a samurai is a ronin, a wanderer without roots. We lack a sacral or even symbolic figure to unite Western Civilization, in contrast to the Muslims with their Prophet or the Japanese with their Emperor. Venner’s quest to find roots — and so set a master over himself and ourselves — is what this book is about.

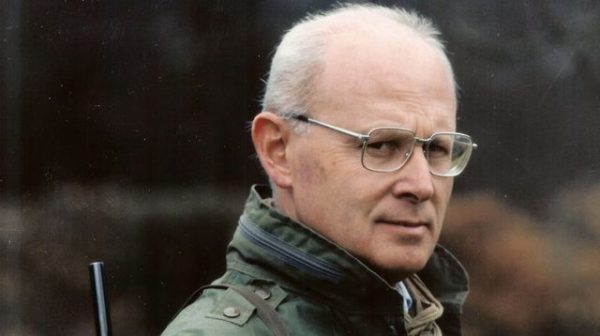

Dominique Venner

Venner gave himself a mission. “Political action is inconceivable without the precondition of a spiritual ideal to inspire it and rebut the ‘we are nothing.’ So, what ideal?” What, then, should be our creed?

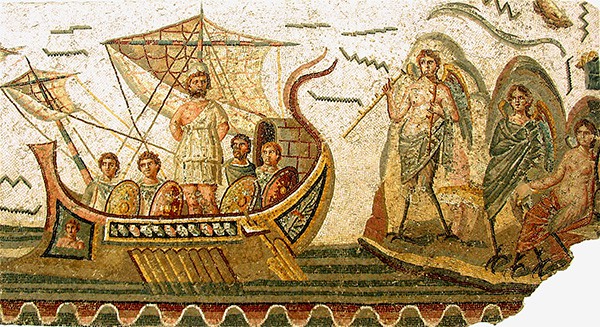

If we identify it, we can know who we are. However, this Spiritual Testament, written near the end of life, is as much a question as an answer. Venner does identify our foundational poems (The Iliad and The Odyssey), an approach (Neostoicism directed towards heroic action), and practical advice about political action. This alone makes the book worth reading, but sometimes it tells us more about how to fight than what we’re fighting for. There is still some work we have to do on our own.

Venner argues that there is a European tradition, “sung since time immemorial and set down in the primeval poems of ancient Greece.” The tradition includes the knightly and aristocratic honor codes such as chivalry and courtly love that appear in different nations, epochs, and creeds. Even Notre Dame Cathedral, forever linked to Venner, has elements of pre-Christian religious iconography. Napoleon turned it into something resembling a Roman temple when he took the Imperial crown from the Pope and crowned himself. The European primeval tradition remains, with Homer as our de facto scripture (as it was for Alexander and countless others in the ancient world), waiting to be rediscovered. The aristocratic cult of heroism, beauty, and nobility remains.

Altar of Notre Dame Cathedral. Credit: Nmillarbc, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This means Christianity cannot be a total departure from our primeval tradition. If it were, it would mean that our roots are shallow. Venner argues convincingly that Christianity, by adopting pagan practices, Greek philosophy, and European marital traditions, remade itself. Thus, Venner lays claim to the Christian era as confidently as to the Classical. Venner notes that it may have been at the Battle of Tours against the Muslims in 732 that disparate Christian groups first thought of themselves as “Europeans” fighting “Arabs.” If Europe came to civilizational consciousness through this battle, to deny Christianity is to deny Europe. Venner is careful not to do that.

In his series “Civilization,” Kenneth Clark not only identified Notre Dame as an example of what is meant by “civilization,” but suggested that Western Civilization was essentially wiped out when the barbarians overran the Roman Empire. If that is so, Christianity deserves credit for saving what was left of Rome.

However, Venner sees what Clark would call the “barbarians” as an invigorating force. Christianity was a product of the late Roman Empire’s decadence. It was a “foreign cult,” but also a universal religion that could unite the diverse peoples within the declining Roman Empire. Venner argues that the success of Christianity was almost a historical fluke. Later, it became the symbol of tradition even though it was its negation. It inverted hierarchies, twisted values, and replaced the sacred homeland with a “City of Heaven” that deserved higher loyalty. This inversion of values set Western man at odds with himself.

Venner argues that Christianity built a gulf between thought and action. Natural inclinations were sinful. The church was needed for salvation. Heroic action was no longer the highest standard. While Christianity may have been useful for the Romans in unifying the decaying empire, Venner argues it divided Europeans over questions of spiritual authority. This occurred both between and within states and even within ourselves. Christianity was the cause of “an enormous spiritual rift, from which Europe has never really healed.” It is the “Unworthy Heir of Ancient Rome.”

And it adapted. Germanic kings, rather than renouncing claims of descent from Odin or Thor, Christianized the practices into “divine right.” Royal courts and scholars prized the classics and popular religious practices preserved paganism with a Christian veneer. “Century after century, revivals have been noticed by historians willing to look for them,” Venner writes about Europeans who looked to our classical past. The true European tradition, he implies, is covered over or co-opted by Christianity and can be discovered in various heresies, movements, and syntactic practices.

One could argue that Christianity didn’t just co-opt the true European tradition but saved it and brought it to its fullest artistic, cultural, and even martial flowering. Hypothetically, an aristocratic warrior religion like the cult of Mithras or Sol Invictus might have swept through the Empire after Christianity. However, we can’t say that glory-hungry warrior bands would have been able defeat invading Muslims as the Catholic ruler of the Franks, Charles Martel, did. One could also argue that Christianity, by tempering the European pursuit of glory, beauty, and power with ideals of charity, mercy, and universal justice, allowed for more efficient and less cruelly governed states.

Venner may not have given Christianity enough credit. Still, he gives us an exhilarating glimpse of the remnants of the pre-Christian European tradition. He notes that from Stonehenge to the mightiest solar temple (or even the Versailles of the “Sun King”), the theme of Olympian Order imposed over primordial Chaos appears again and again. In contrast to Christianity, which Venner argues alienates man from nature, European tradition sees nature as unknowable, mysterious, and sacred. European man is at home within this unknowable force, something that can’t be deconstructed and that therefore terrified people like Sartre. Order also requires limits, both to preserve nature and to maintain balance. Venner calls the battle between limits and growth “Better vs. More.”

“Our myths and rituals sought to match human works to the image of an ordered cosmos,” he wrote. One key passage beautifully unites the Germanic and Mediterranean religious traditions while also describing the European view of nature, order, and the sacred. It also hints at something deeper than Homer when we explore our origins:

Greek temples too arose from the sacred groves of our Hyperborean ancestors. Strabo used to say that “the poets, who embellish everything, call ‘sacred grove’ any sanctuary even if bare of vegetation. Archeological research has shown that archaic Greek temples had tree trunks for columns. The analogy between temple and sacred grove moves us. It was in the high forests consecrated to them that the coarsely-hewn effigies of the gods had first been erected.

St Peter’s Basilica Illuminated Vatican Dome

Thus, we find that even in the greatest buildings, such as St. Peter’s Basilica, we see the Hyperborean sacred grove where our people first knew themselves spiritually. While Venner defends Homer as the founding poet of our people, he also acknowledges we come from something far older. This is a “heritage common to all our European, or Borean, ancestors, be they Celtic, Germanic, Slavic, or Latin:”

For the Greeks, the mythical people of the Hyperborean (those dwelling beyond Boreas, the north wind) lived a happy existence in the North. They are sometimes confused with the Celts. The Hyperboreans worshipped Apollo who, according to legend, spent the three winter months with them. Offerings, attributed to that primeval people, arrived each year at the sanctuary of Apollo in Delos, after having paraded from city to city.

“We Hyperboreans,” wrote Nietzsche at the beginning of fragment 167 of The Will to Power. The memory had been passed down! “We Hyperboreans . . . .”

Venner invokes an ancient, if not eternal Western Man. His spirit is primordial, mysterious, and speaks to us through our blood. From nation to nation and even faith to faith, we see glimpses of the common tradition. However, elsewhere, Venner writes of civilization as something almost transient: “One can destroy a civilization with the stroke of a pen.”

That can happen through immigration. A civilization can certainly be subverted but it can’t die until the people themselves are removed from Earth. That is what we face today, and why the struggle is so important. Questions about marriage, family, immigration, defense, health care and every other policy issue ultimately are the question of whether a people can replace itself, maintain its identity, and grow in power and nobility.

How are we to act? Venner’s Neostoicism accepts death, the natural order, misfortune, and struggle. However, there is no hint of despair or resignation. Instead, he calls us to courage and a new moral order drawn from Homer. “Men therefore are reckoned by the beautiful and the ugly, the noble and the base,” he wrote. “Or, to put it differently, the struggle toward beauty is the condition of the good. But beauty is nothing without loyalty or courage.”

Venner wrote in his farewell note than he expected “nothing beyond, if not the perpetuation of my race and my spirit.” The ancestors he sought to invoke, all the way back to the Hyperboreans, probably did believe in something “beyond.” Still, this changes nothing about the way Venner acted. From the way he lived, wrote, and died, he was Hyperborean.

Faced with this inspiring example, the current war seems even more tragic. Europeans must not be slaughtered for causes not their own. “I have never accepted that the decadence and decay of Europe were our destiny,” Venner wrote. If a dissident can be defined by anything, it must be by this very defiance.

I have strong views about who is right or wrong in this war and what outcome I hope to see, but my foremost conviction goes beyond this war. It has made me think that we’ve focused too much on conventional politics, ceding a higher ideal. Perhaps we should again speak of the white nation, if only as an inspiring myth, something that belongs to all Europeans, to all Hyperboreans. That is a project that could unite people in all white nations who understand that we are one people and share one fate. It would be an achievement worthy of the Iliad. It would be faithful to Venner’s spirit, which still has so much to teach us. It would be a master worth serving.