Why East Europeans Still Have a National Consciousness

Petr Mašek, American Renaissance, September 20, 2019

History often has a keen sense of irony. Sometimes, even in the span of less than a human lifetime, there can be a dramatic shift in how people define freedom or what they see as a decent future. This has certainly been true in Eastern Europe.

Growing up in Communist Eastern Europe was not pretty. People were trapped in a depressing environment of concrete apartment blocks, breathing toxic air from Sovietized heavy industry, often struggling to find toilet paper or fruit and vegetables. You had to watch your language, because the wrong words got you in big trouble. Yet all of this was wrapped in regime propaganda that relentlessly trumpeted a rosy socialist future of equality and justice.

People saw through that. The authorities kept on about prosperity but failed to deliver even basic goods. Even though the West was officially the enemy, products from Germany and the US were deeply desirable. Outside of an extensive black market, Western clothes, electronics, cars etc. were sold only in specialized shopping malls for hard currency that only government officials could get. Hypocrisy and tension hung in the air.

When Communism collapsed in 1989 and 1990, economies were transformed into wild capitalistic systems and we turned to the West, often ferociously. What was Western and especially American, was cool. A lot of young people went West with hopes for a better life, often working in low-wage jobs in degrading conditions. We looked up to the West as a superior civilization with more freedom and better living standards.

This started to change. On the one hand, it is only natural that any outburst of affection should fade over time, but in this case, there were also other reasons. By the early 2000s the first era of joyous Westernization was over and people started to notice that the West wasn’t as awesome as they had believed. They began to mock maudlin American TV shows, Southern creationists, and the general level of American education, especially after G.W. Bush took office.

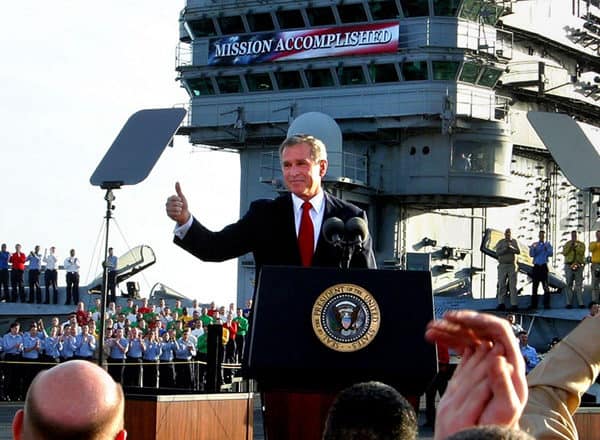

When the US went to war against Iraq, disillusion grew deeper, even though most people recognized that the West and the US were the part of the world to which we naturally belonged. There were squabbles over American anti-missile radar placement and so on, but nobody really questioned our deep cultural ties.

The migrant crisis changed everything. Migration and population replacement were issues that shattered Europe and the West. Here are the reasons why, in my view, Central and Eastern Europeans reacted differently to the greatest challenge of our time. The reasons are deeply rooted in our history.

- Europe has never been as united as people believe.

This may seem strange to Americans who witnessed the melting pot of Europeans, but think of how the Irish or Italians were treated. Were they considered proper Americans right from the start? Now imagine how big and diverse a place Europe is. It has developed a multitude of identities and approaches towards other cultures. It is vital to understand that big parts of Europe had relatively little contact with each other and therefore have different values, even though we are of the same race.

National identity in Eastern Europe was not forged the same way as in France or Britain. Western powers had colonies, and over time started to consider colonial people subjects or even citizens. Eastern Europe was different. Because virtually everyone was white, the main dividing line was not race, but religion, language, and ethnicity. And by living side by side, East Europeans learned unerringly to recognize who’s who. Westerners have loose definitions of who’s English, French, or American; we have absolutely clear ideas who can and can’t be Hungarian, Polish, Czech or Lithuanian.

- Small nations have strong self-preservation instincts

This is obvious, but often neglected because it’s been a long time since we had a major war in Europe. Central/Eastern Europe has always been between the hammer and the anvil. Germans in the west, Russians in the east, Ottomans to the south, all with tendencies to expand and conquer. Life was a constant struggle for our ancestors. Knowing you are in ever-present danger, you develop a deeply rooted sense that you have to be careful. Never back down, or you will be swallowed up. Small nations can be overrun by a massive wave of foreigners, and you may suffer for centuries before you get a chance to be free again. Therefore, Eastern Europeans have a very strong sense that the nation and its freedom are very fragile, and it’s always better to fight a threat in its infancy.

- People are tribal and foreigners will never be loyal

Central/Eastern Europe is a diverse place, where cultures mix and impinge on each other. Western Europe has more or less clear borders between nationalities; it’s common to find a mountain range, a river or an island that marks boundaries. Things don’t work that way in the East, which is more like Northern Ireland, with chaotic distributions of minorities like spots on a dalmatian. It’s often hard to find a city or village with a clear ethnic majority, and there are frequent arguments over ownership.

And this is the crucial point: Regardless of ethnicity, everyone recognizes that people are loyal to their ethnic interests, and when you have foreigners in your state, you have trouble. They will never be fully loyal, and when things get tense (and they always do), foreigners will be a fifth column.

I have an excellent example of a fifth column from the history of my own country. When the Second World War was looming, Germans were about 30 percent of the population of Czechoslovakia, and Hitler made excellent use of them. He appealed to ethnic loyalty and overwhelming numbers of Germans rejected Czechoslovakia and accepted German citizenship. Before the outbreak of war, German parts of Czechoslovakia were full of insurgencies and public unrest, which undermined the integrity of the Czechoslovak state.

“Ethnic Germans in Saaz, Sudetenland, greet German soldiers with the Nazi salute, 1938.” Source: Wikipedia.

To be fair, pre-war Czechoslovakia didn’t treat them as equal citizens either, but that only exaggerated the insurgency; it wasn’t the main cause. After the war, all three million Germans were expelled. This remains controversial to this day, mostly because of the morality of collective guilt, etc. Yet almost all people recognize that separation was the only way to have long-term reconciliation.

This historical experience is deeply rooted in our DNA, and people of our country understand ethnic ties. They learned the hard way. Why did the Roosevelt administration put the Japanese into relocation camps? Because they were a security risk, and back then it wasn’t politically incorrect to say so.

- Leftist indoctrination didn’t reach its full potential here

This may seem surprise readers. You may think that being trapped behind the so-called Iron Curtain for 40 years, we were red to the core. That’s true to a degree, but Soviet communism was entirely different from contemporary Western leftism. It focused heavily on unions, military spending, and potential war against the West. Eastern European communism was therefore nationalistic — in terms of building a strong communist motherland — and socially conservative. It upheld the traditional family, venerated women as mothers and caregivers, kept borders closed, and persecuted people with “alternate lifestyles,” such as hippies (yes, we had some) and homosexuals. On top of that, people remember how it kept on lying about a rosy future, while failing to meet basic needs. This made people distrustful of any official slogans.

“Glory to the mothers of heroes.” Soviet propaganda from 1944.

Western leftist indoctrination started with the so-called “Long March through the Institutions” in the late ’60s and started subtly. It began with reasonable-sounding demands for civil rights, acceptance of homosexuality, etc. and created a new generation of people gradually radicalized against their own families and countries by leftist teachers. Would Westerners have accepted gender fluidity and women in combat in the early ’70s? No, it had to be a gradual process.

In Eastern Europe, people who had lived in very socially conservative societies were suddenly exposed to radical leftism out of the blue. To most of us, leftist orthodoxy seemed too bizarre even to take seriously. With mass tourism, social media, and the internet, people are now exposed to the sad state of the West. Thirty years ago, no one could have imagined the horrors we see firsthand.

The common reaction? “That is not the West we dreamed of and we don’t want it here!”

People in the West are likely to be greatly encouraged by what I have written, but the countries of the former Soviet bloc have distinctive problems. One is that economically we are still behind the West. Many young people go to Germany, the UK or Scandinavia for a higher standard of living. We still suffer from corruption and bad infrastructure. Young people do not feel secure enough to start families or buy houses, and this contributes to dangerously low fertility rates.

We also have a labor shortage, which means we have an immigration problem. Immigrants are mostly from the poorest regions of the former USSR who come to fill the demand for cheap labor, especially in construction. So our cities are full of Ukrainians, Romanians, Bulgarians etc. who are no great threat to our culture.

But they create a different problem. Because our countries are still largely nationalist but European, it’s easy to nurse old grudges. You can still get more political points in the Czech Republic with anti-Russian slogans than by pointing out the potential threat of Third-World immigration. It’s easier for Hungarians to denounce Slovaks and Romanians than to stand united with them. This means that we have healthy national cores, but our nationalism is sometimes directed in the wrong direction.

Finally, our political culture is far more authoritarian than in the West. This can give rise to political leaders who serve themselves and have no shame doing so. Our elites are selfish and, like most elites, are leftist. Unless leaders have strong religious conviction like those of the current Polish government, there is a real danger they can be bribed by trade concessions or a well funded George Soros NGO. The people have to keep constant pressure on their rulers to scare them away from such temptations.

Will Central and Eastern Europe survive? I believe we will be scarred by the madness of the West, but the scars will not go deep. It’s not our leaders to whom we should be grateful but to our historical experience and distinctive development. Our countries are poor and have no colonial connections that would attract Middle Eastern or African migrants. We have been lied to for too long to believe what we are told, and we feel no historical guilt that others can exploit.

What does not destroy us makes us stronger.