The Chinese Who Saw the Perils of Westernization

Sacco Vandal, American Renaissance, October 28, 2016

Many Westerners fear the decline of their own society while they foresee Chinese ascension and impending dominance–with alternating tones of fear or enthusiasm. The United States is growing demographically and may remain a viable cultural entity, but the consensus is that Europe faces demographic disaster. China and the West seem to be approaching an inversion of their relationship of just over a century ago, during the late Qing period, when the West was dominant and China was peripheral. [1]

Patrick Buchanan described the Western dilemma in 2008:

What happened to us? What happened to our world? When the twentieth century opened, the West was everywhere supreme. For four hundred years, explorers, missionaries, conquerors, and colonizers departed from Europe for the four corners of the Earth to erect empires that were to bring the blessings and benefits of Western civilization to all mankind. . . . Whatever became of those men? Somewhere in the last century, Western man suffered a catastrophic loss of faith–in himself, in his civilization, and in the faith that gave it birth. [2]

Although the United States remains the strongest–but not the sole–superpower, European peoples are in decline everywhere. In another book, Mr. Buchanan points out that “In 1960, people of European ancestry were one-fourth of the world’s population; in 2000, they were one-sixth; in 2050, they will be one-tenth. These are the statistics of a vanishing race.” [3] Mr. Buchanan is hardly the first to warn of impending doom for the West. The lamentations of Oswald Spengler (1880–1936) are well known. Less known, however, are the Chinese from the same period who dreamed of a resurgence for China and warned of Western decline. These voices from the late Qing Dynasty may now seem prescient.

Spengler saw the First World War as a sign of the West’s inevitable decline. Many of the Chinese literati who had at first been smitten with the dynamism of the West also came to see the war in the same way: Western civilization was in a state of crisis that would lead to its destruction. Today, Mr. Buchanan also calls the First World War a “mortal wound” that was “inflicted upon our civilization.” [4] Meanwhile, the Chinese, who have resurrected many of the tenets of their traditional civilization after decades of Maoist rule, argue that Western liberalization and democratization are not the True Way by which they will inherit the Earth. As China begins to return to traditional Chinese pragmatism and the West implodes, certain late Qing intellectuals now appear vindicated.

Devastation after WWI.

First among them were Yan Fu (1854–1921) and Liang Qichao (1873–1929). The dynamism of the West at first impressed them, leading them to promote Westernization in China. However, by the end of their lives, both men had come to see the dynamism of the West as self-destructive. They exhorted China to take a middle path between traditionalism and modernization, hoping that this might by the key to supplanting the West.

China in trouble

In the latter half of the 19th century, China was at a technological and military disadvantage. It lost a series of wars with Western powers and was forced to accept unequal treaties. This led various ministers of the Qing Dynasty, such as Li Hongzhang (1823–1901) to advocate mild forms of modernization. Meanwhile, the Meiji government in Japan had started an ambitious effort of full-scale Westernization beginning in 1868. And in 1895, after Japan defeated China in the Sino-Japanese War, it became obvious to most Chinese intellectuals that their nation’s program of limited modernization was not enough.

Until the mid 19th century, Europe had been an inconsequential backwater for China. As late as 1793, a British attempt to establish a greater amount of trade with the Qing was rebuffed with the assertion by the Qianlong emperor (1711–1799) that China “possesses all things in prolific abundance and lacks no products within its own borders,” and thus had “no need to import the manufactures of outside barbarians.” [5] By the mid 19th century, industrialization had made the West vastly more rich and powerful. However, some Chinese thought the sudden dynamism of the West also had intellectual origins.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, China found itself at the mercy of the Western powers that it once looked down upon.

Darwin’s dangerous idea

In 1895, Yan Fu was superintendent of the Beiyang Naval School. In an explanation of Western civilization to fellow Chinese intellectuals, he focused on the theory of evolution. As a young man, he had studied in England and become familiar with social Darwinism, and came to see it as the cultural fountainhead of wealth and power. “Since the publication of [Darwin’s The Origin of Species],” wrote Yan, “of which nearly every household in Europe and America now has a copy, there has been a tremendous change in the scholarship, politics, and religion of the West. The claim that the revolution in outlook and intellectual orientation occasioned by Darwin’s book exceeds that of Newtonian astronomy is hardly an empty one.” [6] Yan spent the next ten years translating works on English evolutionist thought by men such as Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) and Thomas Huxley (1825–1895) in the hope of converting his colleagues to social Darwinism.

Yan Fu was attracted to social Darwinism while studying in England.

Perhaps it took an outsider to see the power of evolutionary thought. Darwin’s theory shook Westerners but it also gave them a certain will to power. Herbert Spencer, who coined the term “survival of the fittest,” led the transformation of Darwinism into social Darwinism, which called upon Western man to glorify victory in social competition. Victory in competition was the purpose of all life everywhere.

Yan quickly saw the winning-at-all-costs ruthlessness of social Darwinism as a remedy for China. Writing in his work on Yan’s life, Benjamin Schwartz writes:

What interests [Yan] is not so much the Darwinian account of biological evolution qua science. It is precisely the stress on the values of struggle–assertive energy, the emphasis on the actualization of potentialities within a competitive situation. The image of ‘nature red in tooth and claw’ does not depress him. It exhilarates him. [7]

Yan nevertheless worried that it might be too late for China to adopt social Darwinism, and that his country would be overwhelmed by the nations that had. In a 1895 newspaper essay, “On Strength,” he wrote:

Months and years slip by, and with rapacious neighbors all around, I fear that we will be too late, that we will follow Poland and India, providing an example of Darwin’s [elimination] before we have been able to implement Spencer’s methods. . . . Alas, our individual lives are not worth the worry, but what of our descendants, and the 400,000,000 of our race? [8]

The battle for reform

After defeat in the Sino-Japanese war, many Chinese intellectuals, such as Yan, began to advocate full-scale Westernization. Japan had already adopted social Darwinism in its pursuit of Western wealth and power, and the Chinese intelligentsia began to believe that China should follow suit. In 1898, the Guangxu emperor (1871–1908) appointed the minister Kang Youwei (1858–1927) to head a reform movement after Kang had requested permission to imitate Japan:

As to the republican governments of the United States and France and the constitutional governments of Britain and Germany, these countries are far away and their customs are different from ours. Their changes occurred a long time ago and can no longer be traced. Consequently I beg Your Majesty. . . to take the Meiji Reform of Japan as the model for our reform. The time and place of Japan’s reform are not remote and her religion and customs are somewhat similar to ours. Her success is manifest; her example can easily be followed. [9]

The emperor agreed, and the minister initiated a flurry of Meiji-style reform. A bright young man named Liang Qichao worked with Kang as his protégé, and he became one of the most influential Chinese advocates for Westernization. However, Kang and Liang’s efforts were quickly aborted after an imperial coup under the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908).

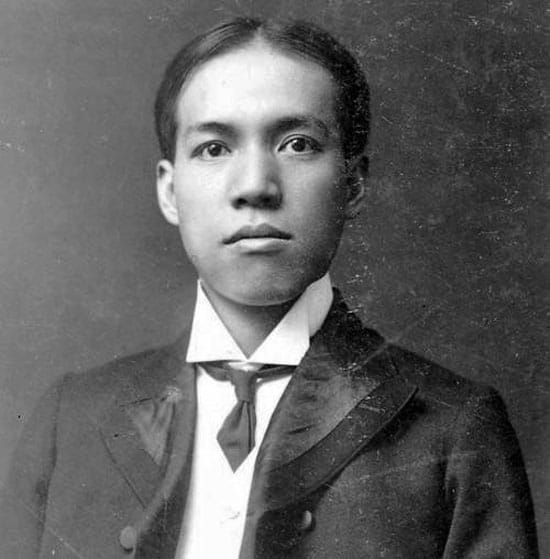

Liang Qichao

After the Empress Dowager cut short what later became known as the Hundred Days Reform, Kang and Liang escaped political persecution by fleeing to Japan. Once there, Kang continued to support the Qing dynasty and to justify an agenda for Chinese reform via cautious appeals to Confucianism. Liang, however, ultimately broke with Kang and–like Yan–began to espouse “a new view of world history strongly colored by social Darwinism: a struggle for survival among nations and races.” [10]

He wrote:

If we wish to make our nation strong, we must investigate extensively the methods followed by other nations in becoming independent. We should select the superior points and appropriate them to make up for our own shortcomings. [11]

Liang increasingly came to see social Darwinism as the fuel of the West’s dynamism, one of the “superior points” that China would do well to “appropriate.” Writing from Japan, he exerted great influence on young Chinese. Together, Yan and Liang instilled in an entire generation of Chinese students a fervent desire for change. But this influence did not bring social Darwinism to China. Instead, it brought the 1911 Revolution, the New Cultural Movement (1915–1921), and the May Fourth Movement of 1919–perturbations that would spin China into over half a century of upheaval.

Accommodative versus transformative thought

Despite their attraction to social Darwinism and their sometimes radical calls for reform, Yan and Liang were not revolutionaries. Indeed, although Liang and–especially–Yan attacked various instances of Chinese backwardness, they continued to support the Qing Dynasty, advocating slow transition into a constitutional monarchy based on the British model. Once the 1911 Revolution succeeded, however, Liang grudgingly threw his support behind the new republican government, but Yan continued to support monarchy.

Questioning the West

The First World War was a shock to reformers who wanted to embrace the West. As the war dragged on, aging reformers such as Yan and Liang became increasingly disillusioned with not only transformative revolution, but Westernization and even the West. Yan wrote that the carnage of the war was a consequence of Western traits: “Such has been the effect on the human race of civilization and science! When I look back on our [Chinese] sacred wisdom and culture, I find that it foresaw this even at that early date. . .” [12]

Yan explained further:

As I have grown older and have observed the seven years of republican government in China and the four years of bloody war in Europe–a war such as the world has never known–I have come to feel that [the West’s] progress . . . has lead only to selfishness, slaughter, corruption, and shamelessness. When I look back upon the ways of Confucius and Mencius, I find that they . . . have profoundly benefited the realm. This is not my opinion alone. Many thinking people in the West have gradually come to feel this way. [13]

Liang wrote that “recently many Western scholars have wanted to import Asian civilization as a corrective to their own,” and, indeed, the latter half of the 20th century saw the importation of philosophical, religious, and cultural curiosities from the East and into the West. In the meantime he stated his goal for China:

I therefore hope that our dear young people will, first of all, have a sincere purpose of respecting and protecting our civilization; second, that they will apply Western methods to the study of our civilization and discover its true character; third, that they will put our own civilization in order and supplement it with others’ so that it will be transformed and become a new civilization; and fourth, that they will extend this new civilization to the outside world so that it can benefit the whole human race. [14]

Because of the devastation of the First World War, these two thinkers who had once promoted modernization and Westernization instead advocated a modernization without Westernization (or at least minimal Westernization). They seemed to believe that the course of the West was not sustainable and that the West could be supplanted by China if it modernized in a way that was compatible with its nature and culture. They seem to have realized that social Darwinism was a false promise, and that the forces it unleashed could destroy the West.

China and the West today

In the end, China did not follow Japan down the path of Westernization. A burgeoning Chinese nationalism grew up around anti-Japanese sentiment, and this enmity was extended to the West after Japan instead of China was awarded Germany’s Chinese concession at Versailles in 1919. Ultimately, communism on the Soviet model provided the Chinese with an alternative to both Chinese traditionalism and the West. China entered a period of socialist tyranny under Mao Zedong (1893–1976).

After Mao’s death, China began to abandon Maoism. It is still nominally communist, but since the 1980s, it has followed the example of Hong Kong and Taiwan and has increasingly returned to the teachings of Confucius and Mencius. Chinese now praise Yan and Liang for their wisdom and prescience. The post-Mao leadership of the People’s Republic of China–beginning with Deng Xiaoping–has espoused views nearly identical to those advocated by Liang over a century ago. [15]

At the same time, Westerners are now studying the warnings of Yan and Liang about the inherent instability of the West. As Western liberals such as Martin Jacques herald the coming Chinese domination, there may be a generation of European and American scholars who find themselves in a position similar to that of Yan and Liang: struggling to understand why their civilization has fallen behind that of a rival whose inferiority was once taken for granted.

Thus, while China has found its way back to the middle path, balancing its modernization and Westernization with pragmatism, caution, and Confucianism, the West is disintegrating in a chaos of heterogeneity and decadence. The warnings of Spengler have come true, and Patrick Buchanan forecasts the death of the West. Russia and parts of Eastern Europe are trying to save themselves from liberalism and democracy, but success is not guaranteed.

Thinkers in the Alt-Right are wrestling with the question of how to save our own white civilization. The old order is collapsing due to challenges from abroad and the immigrant invasion. Non-whites are chopping up the West the way the West once chopped up China. We are Yan Fu and Liang Qichao. We must forge a plan for the preservation of our race.

- See Patrick Buchanan, The Death of the West(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002); David Goldman, How Civilizations Die(Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2011); Martin Jacques, When China Rules the World(New York: Penguin Press, 2009); Larry Kelley,Lessons From Fallen Civilizations (Austin: Hugo House Publishers, 2012); Mark Steyn, America Alone (Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2009); and Fareed Zakaria, The Post-American World (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008).

- Patrick Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War(New York: Random House, 2008), ix-x.

- Patrick Buchanan, Death of the West(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002), 11-12.

- Patrick Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War(New York: Random House, 2008), 502.

- “Modern History Sourcebook: Qianlong: Letter to George III, 1793” Internet History Sourcebooks, accessed March 20, 2014,https://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1793Qianlong.asp.

- Yan Fu, “On Stength” in vol. 2 of Sources of Chinese Tradition, edited by William Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 256.

- Benjamin Schwartz, In Search of Wealth and Power(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 46.

- Yan Fu, “On Stength” in vol. 2 of Sources of Chinese Tradition, edited by William Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 258.

- Kang Youwei, “The Need for Reforming Institutions” in vol. 2 of Sources of Chinese Tradition, edited by William Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 270.

- William Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano, ed., Sources of Chinese Tradition, vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 288.

- Liang Qichao, “Renewing the People” in vol. 2 of Sources of Chinese Tradition, edited by William Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 290.

- Yan Fu, quoted in In Search of Wealth and Power, Benjamin Schwarz (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 235.

- Yan Fu, quoted in In Search of Wealth and Power, Benjamin Schwarz (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 235.

- Liang Qichao, “Travel Impressions from Europe” in vol. 2 ofSources of Chinese Tradition, edited by William Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 378-379.

- See Max Ko-wu Huang, The Meaning of Freedom(Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2008), Chapter 1; and Orville Schell, Discos and Democracy: China in the Throes of Reform(New York: Panteon Books, 1988), chapter “Liang Qichao: China’s First Democrat.”