The Color of Corruption

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, April 12, 2018

Simón Bolivar, revered by Latin Americans today but scorned at the end of his life, famously prophesized:

[Latin] America is ungovernable: Those who have served the revolution have ploughed the sea. These countries will inevitably fall into the hands of the disenfranchised multitude to then fragment into small tyrannies of all colors and races, devoured by their crimes and extinguished by their own ferocity.

Events since then have proven him wise. However, Professor Edwin Lynch of Hollins University, a former staffer in the Reagan White House, believes he has the solution to Latin America’s woes, particularly endemic corruption. In a column entitled, “Latin American democracy is crumbling under corruption” in The Hill, Professor Lynch argues federalism would ameliorate the desperate situation. “Every element of the corruption epidemic can be addressed through federalism on the North American model, an example that Latin American nations would do well to imitate,” he argues.

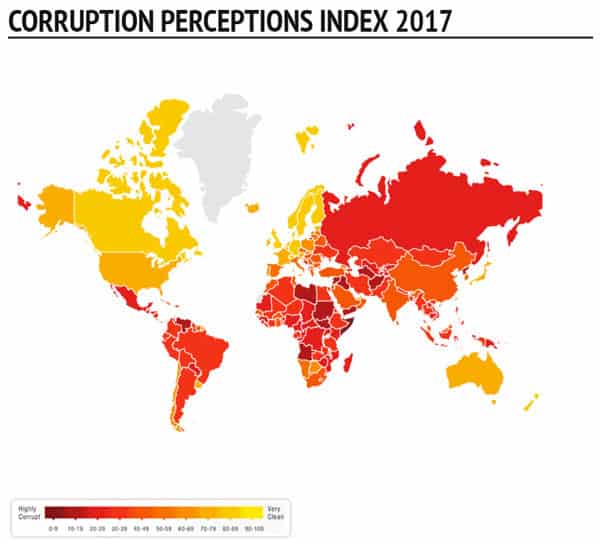

Professor Lynch is correct about how corruption undermines Latin American democracy. He provides anecdotal examples about leaders in Venezuela and Bolivia attempting to cling to power and touches on recent scandals in Argentina, Ecuador, and Brazil. Professor Lynch is supported by research. According to Transparency International and its “Corruption Perception Index,” Latin American nations generally score far behind Western European and North American nations when it comes to public perception of corruption.

According to the organization’s report “People and Corruption: Latin America and the Caribbean,” more than half of those polled said their governments failed to address corruption. In Mexico, a majority reported having personally paid a bribe to access basic services in the previous 12 months. Most of those surveyed also thought corruption had increased in the last 12 months.

Professor Lynch’s solution is conventionally conservative, emphasizing limited government. “Corruption comes from the combination of excessive government power and insufficient intra-government competition,” he writes. “The first puts government officials in charge of too many people’s lives and livelihoods. The second ensures that bribery and lucrative conflicts of interest take place without accountability.” He further faults a political culture resulting from “decades of dictatorship,” enabling officials to steal “without a pang of conscience.”

Yet Latin America’s most obvious problem is the inability of the government to perform its basic function of maintaining order. Only a few years ago, figures such as Michael Moore and Oliver Stone were cheerleading the “Bolivarian Revolution” of Venezuela, but today the country is almost dystopian. One recent story in the Miami Herald chronicled how gangs of machete wielding youths fight in the streets over garbage. El Salvador and Honduras aren’t much safer.

Simón Bolivar

Mexico, wealthy by global standards, can’t protect its own officials. The organization Justice in Mexico reports that 150 mayors, mayoral candidates, and former mayors have been assassinated between 2000 and 2017. The Mexican government risks its own elite soldiers defecting to the cartels, which are extending their reach even into Columbia, according to a recent report from Reuters. Meanwhile, a left-wing militant group called the Zapatistas maintains control over a large area of the Mexican state of Chiapas.

In Brazil, the fight against corruption has ensnared former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. A poll released last month showed he would have “easily won” Brazil’s October election, but instead he will be jailed for overseeing a “a billion-dollar network of corruption.” The new frontrunner, Jair Bolsonaro, is a former military man who is drawing support from those who remember the military dictatorship with nostalgia because it provided law and order. Brazil relies on the military to combat gangs in Rio de Janeiro, though without much success. The murder of an anti-military campaigner by unknown assassins has drawn international attention, heightening the political divide. Given recent political chaos, it’s not surprising there’s a minor movement to bring back the monarchy and restore the Empire.

Professor Lynch does not mention race in his analysis of corruption and the decline of democracy in Latin America. This is an oversight considering how race is driving many of the phenomena he decries. For example, Professor Lynch mentioned Bolivia’s leader evidently desires to be president for life, but didn’t mention Evo Morales by name. He also didn’t mention that President Morales took power in 2005 via an explicitly anti-white movement appealing to Amerindians who wanted to, in his words, “expel the white invasion, which began with the landing of Columbus in 1492.”

The opposition to President Morales also has racial overtones. A movement to secede from Bolivia centers on the whiter areas. Similarly, the three majority-white states in Brazil have their own secession movement, and ex-president da Silva was recently shot at when he campaigned in the region. Though secession efforts have thus far been unsuccessful, their existence suggests these nations are not simply divided by geography, as Professor Lynch implies, but also by race.

Blaming the legacy of “dictatorship” for corruption is also unconvincing. Latin American politicians are typical of most of the world, including much of Europe. As Steve Sailer and others have noted, only those societies dominated by northwestern Europeans show low rates of corruption, a pattern seen in Transparency International’s corruption map. Cultures characterized by strong extended family ties lend themselves to nepotism and clan-based politics. The state is regarded as a source of wealth and power to be distributed to the tribe, not as a means of cultivating a common good. The Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon culture of individualism and relatively weak extended families has some social costs, but generally correlates with lower rates of corruption. As Samuel Huntington showed in his book Who Are We?, it’s vitally important that the founding culture of North America is Anglo-Protestant, not Spanish.

Source: Transparency International

There is one notable exception to the Latin American pattern of corruption. The country with the best score in the 2017 Corruption Perception Index was Uruguay. Uruguay is also ranked as a “full democracy” by The Economist based on the magazine’s compilation of factors including civil liberties and the fairness of elections. Journalist Uki Goñi described it as a “quiet democratic miracle” in a February 2016 op-ed in The New York Times, crediting the country with a “deep respect for the rule of law.” According to the “People and Corruption: Latin America and the Caribbean” study, less than 20 percent of Uruguayans thought their police were corrupt.

Uruguay is also almost entirely white. According to the CIA World Factbook, Uruguay’s population is 88 percent white, mostly Spanish and Italian. It has a “practically nonexistent” Amerindian population and only a 4 percent black population. Interestingly, Uruguay actually has a better score on the 2017 Corruptions Perceptions Index (ranked at 23 worldwide) than Spain (42) or Italy (54).

Professor Lynch’s analysis is not only simplistic considering the above, but his triumphalism about the American “federalist” system is misplaced considering it barely exists anymore. On questions ranging from abortion to gay marriage, policy is determined not through local or even democratic institutions but unelected judges. The closing argument each party makes to its supporters every election is the need to keep or retake control of the courts.

Additionally, unelected federal bureaucrats can exercise far more power over Americans than elected local representatives. As chronicled recently at American Renaissance, school districts nationwide were massively impacted by a school discipline directive from President Obama’s Department of Education, despite its dubious legality. Almost every school or business in the country is at risk of federal investigation if there is an accusation of a civil rights violation.

Indeed, communities have practically no power to protect their basic way of life. As Tucker Carlson recently chronicled, towns such as Hazleton, Pennsylvania, have been totally changed by mass immigration even after electing leaders such as Mayor (and now Congressman) Lou Barletta who pledged to resist the invasion. They were prevented from doing so by courts and national activist organizations. Even a state, theoretically powerful under our Constitution, is helpless before a federal judge’s ruling. California’s wholesale transformation following judicial overruling of Proposition 187 shows how hollow “federalism” really is.

As America becomes increasingly multicultural and multiracial, the key political divide is not between states or regions, but between different ethnic groups. Similarly, the “checks-and-balances” system of the Founders has devolved into a struggle to control politically biased courts and a sprawling federal bureaucracy.

Professor Lynch is missing the point. Politics is downstream from culture, but culture is downstream from race. It’s more likely North America will be assimilated into Latin America because of demographic changes than that Latin America will resemble North America because of legalistic tinkering.

Simón Bolivar, that Creole of noble birth who spent his life fighting mostly for non-whites, thought his warning applied only to Latin America. Yet if the “American people” come to resemble those freed by the “The Liberator,” General Bolivar’s prediction will apply to El Norte as well.