“Africa Greets You”: The Anti-White Terrorism of Mark Essex

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, August 26, 2017

A black military veteran uses a high-powered rifle to target white police officers. Like all well-trained shooters, he knows that aiming for center mass is an efficient takedown, but a headshot is a guaranteed kill. His one-man war against the police department is broadcast to millions of American homes. Black citizens cheer him on, convincing the “silent majority” that a race war in a major Southern city is possible.

You probably think this is a description of last summer’s ambush in Dallas. The shooter, a former member of the US Army Reserve who served in Afghanistan, used a Saiga AK-74 rifle, a civilian version of the standard-issue Russian army rifle, to kill five police officers who were providing security for a Black Lives Matter rally. Before being killed by a remote controlled bomb, Micah X. Johnson told police negotiators that he “wanted to kill white people.”

Micah X. Johnson

Such killings are nothing new. The first paragraph describes the massacre committed by Mark Essex, a 23-year-old, ex-military, black man who used a Ruger .44 carbine and a .38-caliber pistol to kill nine people between December 31, 1972 and January 7, 1973. Five were members of the New Orleans Police Department. Then, as now, he blamed police officers — especially white officers — for “systemic racism.”

Born and raised in Emporia, Kansas, Essex lived a fairly ordinary life. Emporia was only two percent black during his childhood. Like most mass murderers, he was described as a “loner.” In 1969, after graduating from high school and very brief stint in college, Essex joined the US Navy. The war in Vietnam was still very hot, but Essex, who served as a dental technician, never went overseas.

Not long after joining the fleet, Essex began complaining that white peers and white petty officers made his life extremely difficult. At the Naval Air Station in Imperial Beach, California, Essex provoked a fight with a white superior. Essex wrote letters back home complaining about white racism. He grew his hair long and ran afoul of military grooming standards. He started reading about the Black Panthers and other militant black organizations. Whether real or imagined, Essex’s encounter with racism in the Navy inculcated in him a hatred for all white people.

Mark Essex

After just two years, Uncle Sam kicked Essex out of the service with a general discharge. Officially, Essex was considered unsuited for the Navy due to “character and behavior disorders.” Once again a civilian, Essex drifted around America. He briefly joined the Black Panthers and lived for a while in San Francisco and New York, before finally settling in New Orleans.

New Orleans had mostly been spared the anarchic violence of the Civil Rights Era. However, the city was hardly a multi-racial paradise. Black Panthers and anti-war demonstrators numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands. In December 1972, Essex mailed a note to WWL-TV, a local broadcasting station, warning about an attack on the New Orleans Police Department planned for New Year’s Eve. This was his letter:

Africa greets you. On December 31, 1972, aprx. 11 p.m., the downtown New Orleans Police Department will be attacked. Reason — many, but the death of two innocent brothers will be avenged. And many others.

P.S. Tell pig Giarrusso the felony action squad ain’t shit.

Mata

The sign off, “Mata,” was what Essex had begun calling himself — meaning “hunter’s bow” in Swahili.” “Giarrusso,” referred to Clarence B. Giarrusso, the police chief at the time. True to his word, Essex drove to Perdido Street and waited for NOPD officers to leave the nearby station on December 31, 1972. He shot black police cadet Alfred Harrell to death and wounded Lieutenant Horace Perez.

Essex fled the scene and broke into a warehouse in Gert Town, a black neighborhood where anti-cop prejudices ran high. Responding officers had no idea that the break-in was related to the murder of Harrell and Perez. K-9 officer Ed Hosli, Sr. was investigating the warehouse at South Gayoso and Euphrosine streets when Essex shot him in the back. Hosli died from his wounds two months later.

Six days after New Year’s Eve, Essex shot and killed a white grocer who had told the police about him. Essex then stole a car and promised its owner that he did not want to kill black people like him, “just honkies.” On January 7th, Essex invaded the Howard Johnson hotel at 330 Loyola Avenue. Essex raced up an emergency staircase to the 18th floor. The first employees he saw were black maids. He told them not to worry — he was there to kill white people.

Essex entered room 1829 and found a white couple, Dr. Robert Steagall and his wife Betty. Essex killed them both, then used lighter fluid and phone books to set the room’s curtains on fire. Essex eventually moved towards the roof. Along the way he killed hotel assistant manager Frank Schneider and shot general manager Walter Collins, who died three weeks later.

From the rooftop, Essex fired on NOPD officers who tried to use fire ladders to get into the burning building. Here more police officers would die from .44-caliber rounds. Officers Philip Coleman and Paul Persigo were shot and killed while taking cover in Duncan Plaza. Deputy Superintendent Louis Sirgo received a fatal wound to his spine while trying to rescue pinned down officers.

Police finally borrowed a Marine Corps CH-46 helicopter to pour fire down on Essex. The two sides exchanged rounds for a time, but after he died, investigators found that Essex had been shot over 200 times.

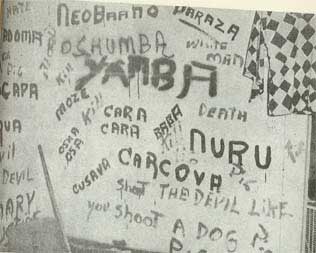

After looking for and failing to find a suspected second sniper, New Orleans Police officers found Essex’s apartment on Dryades Street. Inside, the walls were covered in anti-white graffiti. Most of the words were nonsensical phrases borrowed from Swahili and other African languages. Essex, it seems, thought of himself as a resurrected Mao Mao warrior fighting white settlers.

Interior of Marx Essex’s apartment.

Following Essex’s death, black militants were quick to praise him. Stokely Carmichael said that Essex carried “our struggle to the next quantitative level, the level of science.” More frightening was the real-time, on-the-ground reaction of New Orleans’ black citizenry. When they realized that Essex was targeting white people, they roared “Right on!”

These are the direct ancestors of the Black Lives Matter movement. In allying themselves with the Black Panthers and other militant black organizations, the American Left is turning more people into the likes of Mark Essex. 1973 was a terrible year for white America. Besides the crimes of Mark Essex, San Francisco’s Zebra killers were killing white police officers and butchering white civilians while white and black Leftists cheered them on. The Zebras killed fourteen people, but you have probably never heard of them. Essex held a city in complete terror for weeks, and you’ve probably never heard of him either. Forgetting such history makes whites vulnerable to the next attack.