The Central Park Jogger: The Trayvon Martin of Her Time

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, July 31, 2014

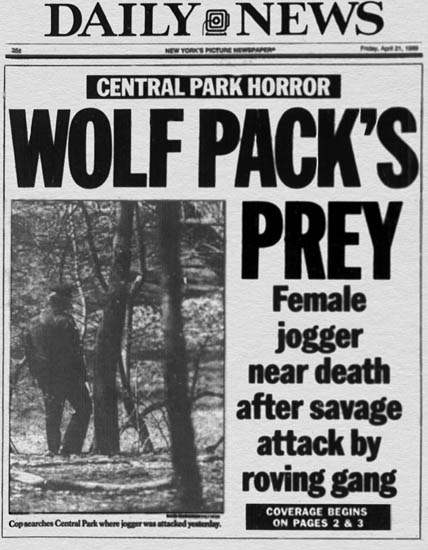

The Central Park jogger rape case is back in the news. The rape and near-murder was part of a sensational attack in 1989 by 30 to 35 black “youths” who swept through New York City’s Central Park, attacking white people. Most of the victims in what came to be known as the “wilding” incident were robbed and beaten, but a 29-year-old woman out for a jog was raped, smashed with a rock, and left for dead. When the police asked her boyfriend to identify the unconscious woman, she was so badly mangled that he recognized her only because of her ring.

Five young blacks were convicted of assaulting her and a number of other whites, but in 2002 their rape convictions were vacated when a Hispanic serial rapist named Matias Reyes claimed that he had committed the crime alone. DNA evidence supported his claim, though it was never subjected to formal cross examination.

It now appears that the blacks did attack the jogger, even if they did not rape her. They admitted to having said, “Let’s get a white woman,” [Michael Stone, “What Really Happened in Central Park,” New York (August 14, 1989), p. 30ff.] during their attack on several other victims, one of whom they knocked unconscious with a pipe. However, they probably managed only to rough up the jogger, and it was Mr. Reyes who caught, raped, and nearly murdered her after she got away from them. She has no memory of either attack.

The blacks filed a civil suit against the city, claiming that the sentences they had already served, ranging from six to 13 years, were excessive. The big news now is that New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has ordered his lawyers to stop fighting the suit, and to settle for a reported $40 million. Even if the city owes the blacks some compensation for longer-than-normal sentences, many people think a $40 million settlement is outrageous.

Plenty else about the case was outrageous–though no one is talking about that now. I was living in New York City during the trial, and I saved clippings from newspapers; this was before the Internet. The way blacks behaved was so spiteful that even the most accommodating whites were shocked; blacks and whites were as divided about the case as they were 25 years later in the George Zimmerman self-defense trial.

As is customary in rape cases, the press voluntarily refrained from publicizing the victim’s name. The reason was to protect her from comments like “You were the one who was gang-raped in Central Park, weren’t you?” when she uses a credit card. Black newspapers usually follow this rule, but they deliberately published the white jogger’s name. [Alex Jones, “Most Papers Won’t Name the Jogger,” The New York Times (June 13, 1990), p. B3.]

The black-owned radio station WLIB repeatedly broadcast her name. [“Rape Victims’ Right to Privacy,” New York Post (July 21, 1990), p. 12.]

It now appears that the trial may have resulted in a miscarriage of justice, but the defendants had made videotaped confessions that left little doubt in most people’s minds. The black paper Amsterdam News, however, insisted from the start that the blacks were innocent of all charges. It repeatedly used the word “lynching” in its headlines, and described the prosecutor and grand jury as “little better than lynch mobs,” with police lined up “to do the lying and dirty work.” [William A. Tatum, “Jogger Trial: The Lynching Attempt That Must Not Succeed,” Amsterdam News (New York) (August 11, 1990), p. 12. “The Jogger Trial: A Legal Lynching to Haunt Us,” Amsterdam News (New York) (August 25, 1990), p. 12.]

The paper’s publisher, William Tatum, explained what was going on:

The truth of the matter is that there is a conspiracy of interest attendant in this case that dictates that someone black must go to jail for this crime against the “jogger” and any black will do. The rationale being the belief that blacks are interchangeable anyway. [Amy Pagnozzi, “Idiots Who Jeer Jogger Merit Only Contempt,” New York Post (July 23, 1990), p. 4.]

The City Sun, another black paper, was miffed at New York Post columns that criticized the way blacks were covering the trial. It began calling the Post “New York’s apartheid paper.” [“The Governor Joins the Anti-Apartheid Struggle,” City Sun (July 18-24, 1990), p. 30.]

A faithful group of blacks attended the trial and cheered the defendants as if they were heroes. When the rape-victim jogger arrived to testify, still disfigured and unsteady, they screamed that she was a whore and that she had been raped by her boyfriend. [Jim Nolan et al., “Jeering Spectators Add Insult to Her Injuries,” New York Post (July 17, 1990), p. 4. Mike McAlary, “Racism Comes in Many Shades,” New York Daily News (July 18, 1990), p. 4.]

The prosecutor, Elizabeth Lederer, was repeatedly threatened by defendants and their supporters. [“Disorder in Court,” New York Post (December 15, 1990), p. 24.] After the guilty verdicts were announced, black spectators shouted curses and insults at the jogger–who was not there–and at the prosecutor. Blacks in the court-house hallway shouted “filthy white whore,” “white slut,” and “People are going to die.” [Mike McAlary, “Courtroom Chaos a Living, Breathing Sculpture of Hate,” New York Post (December 12, 1990), p. 8.] The prosecutor had to be protected by 12 policemen as she left the courthouse, followed by about two dozen blacks shouting, “liar,” “prostitute,” and “You’re gonna pay.” [Chris Oliver et al., “Courtroom Mob Scene Spills into the Street,” New York Post (December 12, 1990), p. 8.]

Thomas Galligan, the judge who presided over the trial, repeatedly received anonymous death threats. He sentenced one man, who threatened him publicly, to 30 days in jail for contempt of court. [Jim Nolan, “Judge Bares Death Threats During Trial,” New York Post (January 10, 1991), p. 2.]

Perhaps the low point in trial was a one-day appearance by Tawana Brawley, who had perpetrated a spectacular white-on-black rape hoax just two years earlier. She came to congratulate and show solidarity with the heroes/martyrs. A spokesman for Miss Brawley explained that she had also come to “observe the differences in the court system between a white and a black victim.” [Ronald Sullivan, “Police Said to Ignore Warnings on Jogger Suspect,” The New York Times (July 31, 1990), p. B3. Ray Kerrison, “Trial was Turned into a Circus,” New York Post (August 20, 1990), p. 4.]

One of the strongest expressions of the black view of the trial was a guest editorial in the Amsterdam News that appeared well before the jury had reached its verdict:

[I]t strikes me as utterly ironic and hypocritical that, as in most court cases these days, a group of white people can sit in judgment of [sic] diminutive young Black males and pretend that they are about the business of ‘justice.’

Considering the fact that not one of the whites . . . judge, jury, security guards, lawyers, have ever had their ‘racism quotient’ measured; and each one has been conditioned by an admittedly institutionally racist society; I sit on this hard wooden courtroom bench in agony–hardly able to contain my outrage and anger at what I know in my gut is a continuing obscene exercise in public masturbation, with Black lives and psyches as the seemingly endless fodder in a system set up by white males for the benefit of white males. [Carol Taylor, “The Jogger Case: Notes From a Courtroom,” Amsterdam News (New York) (June 30, 1990), p. 14.]

The racial divide will not go away. It was the same in the Trayvon Martin Case and in the O.J. Simpson trial. It was the same when police were tried for beating Rodney King. It could not be clearer that blacks and whites see the world differently–and yet a few whites still seem to believe that someday both races will see it the same way.

[The references to the 1990 trial are taken from Paved With Good Intentions, which is now available as a Kindle book.]