Pathological Altruism

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, July 6, 2012

Barbara Oakley, Et. Al, Pathological Altruism, Oxford University Press, 2012, 465 pp., $55.00.

Pathological Altruism is a fascinating book. As a long-time student of the most common and dangerous of all pathological altruisms — the willingness of whites to give up their homelands to non-whites — I was hoping at least one of the 48 contributions would mention this problem. None does, but several throw useful but indirect light on it. The book is also filled with eye-opening observations about human nature and how the brain works, and its main editor, Barbara Oakley of the University of Michigan, has done a wonderful job of eliminating repetition and contradiction. Even Edward O. Wilson of Harvard has written that this book taught him something completely new, and I believe him.

“Pathological altruism” (PA) is a relatively new concept; the term entered the scientific literature only in 1984. There has been very little written about it, partly because altruism is so highly regarded in the West that few scientists dare criticize it. This book makes it clear that PA is a problem well worth studying.

PA is generally defined as a sincere attempt to help others that instead harms others or oneself, and is “an unhealthy focus on others to the detriment of one’s own needs.” Several of the contributors offer tantalizing definitions: PA is likely when people “falsely believe that they caused the other’s problems, or falsely believe that they have the means to relieve the person of suffering.” Or, it is “the false belief that one’s own success, happiness, or well-being is a source of unhappiness for others.” PA “often involves self-righteousness,” and can result in “impulsive and ineffective efforts to equalize or level the playing field.”

Together, these definitions are an almost perfect description of white liberal attitudes towards non-whites, yet none of the contributors seems to be aware of this.

A typical case of PA is the battered wife who thinks her own behavior makes her husband violent, and who stays with him because she fears he will commit suicide if she leaves. Another would be a depressed person who mistakenly believes that if he kills himself he will no longer be a burden on his family — and so he kills himself. Some people falsely think their own success comes at the expense of family members or co-workers, and try to make amends for their undeserved achievements.

What is known as co-dependency, or helping someone who is obviously hurting himself, can be another kind of PA. Examples would be giving too much food to an obese child or lying to a spouse’s employer to cover up his alcoholism. Co-dependents often have low opinions of themselves, and sacrifice their own needs for the person they are caring for. Sometimes they are driven by an inability to tolerate unhappiness or anger from the object of their PA; again, a good description of how whites treat non-whites.

“Animal hoarders” are another example of PA. They fill their houses with “rescued” pets but fail to look after them. They declare their love for animals even as they step over the bodies of dogs and cats that have died of malnutrition. They often neglect their own health, living in tumble-down houses filled with animal filth. These people usually started out with a strong childhood attachment to animals but were neglected or abused by their own parents. They often start hoarding after they suffer some kind of personal setback, such as a divorce or losing a job.

People who have chronically sick family members sometimes become pathological altruists, devoting themselves to serving the patient. If they, themselves, get sick, they tend to believe they are a painful burden to others and to refuse help.

Anorexics have a streak of PA in them. Most are women, who were unusually considerate and giving when they were children. As they get older, they want to feed and look after people, even as they starve themselves. Some refuse sleep or medical care; not just food. People with eating disorders are very good at reading the moods needs of others, and clinics for them are full of women trying to take care of each other. Most anorexics are white.

Human Nature and Biology

Empathy and altruism can clearly get out of hand, but they are part of human nature. Even infants and toddlers show signs of empathy, and try to help people in distress. When babies hear other babies crying, they cry in sympathy. However, if children have been abused or live in tense households they may be hostile to people who are suffering.

Almost all adults sympathize when they see suffering — those who do not are psychopaths — and this instinct appears to have evolved for two reasons. Altruism within the family or kin group makes evolutionary sense because the beneficiaries carry many of the same genes as the altruist. Also, our evolutionary environment was one in which we could easily find ourselves face to face with people who had less food than we did. We probably evolved an impulse to share, both because this improved social relations, and because those we helped might someday help us. This is probably why beggars make people uncomfortable; they stimulate our built-in urge to share. Some people give in to that urge but others just try to get away from beggars.

Experiments in which people are tested to see how altruistic they will behave under controlled conditions suggest that we are a lot more altruistic than we need to be — and in fact people often do return lost wallets, donate blood, and do favors for people they will never see again. One of the contributors, Satoshi Kanazawa, theorizes that this is because the brain has a hard time comprehending things that never happened in the small-band evolutionary environment: “Contemporary humans may cooperate with genetically unrelated others, mistakenly (and unconsciously) thinking that they are kin or repeated exchange partners.”

There is no genetic or material payoff for being nice to total strangers, but we are nice to them because our distant ancestors rarely had to deal with total strangers. Cheating and stealing would make better sense, but we treat strangers like members of the tribe.

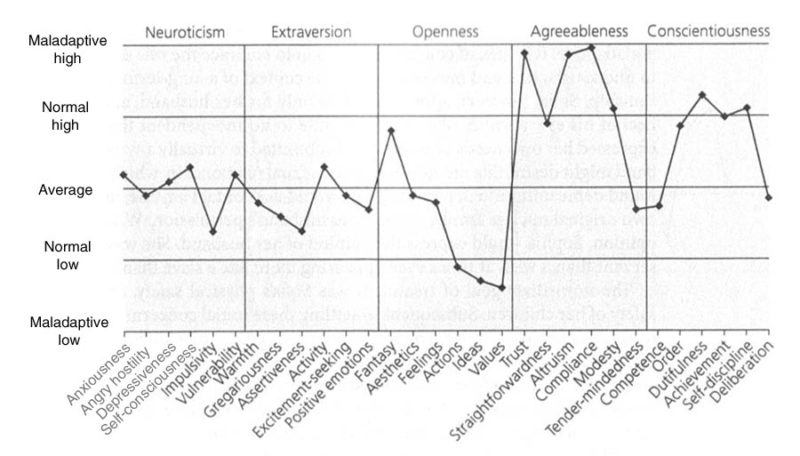

What makes altruism go off the rails? One theory is that it can simply be an extreme example of a personality trait we all have. Psychologists talk about the Five-Factor Model of personality, which measures neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Pathological altruists may be too agreeable, and therefore let people take advantage of them. The graph below (from page 89) is the personality profile of a woman who lived entirely for her husband and her family. She was self-sacrificing, docile, and had no ideas of her own. She was more like a servant than a wife, and her husband beat her. Whites, as a race, are excessively “agreeable” to other races.

We can detect agreeableness and friendliness, even in strangers. Studies of rapists suggest that they target women who seem open and agreeable. People who are considerate also tend to marry each other — though some givers end up enslaved to takers.

Another theory about the origins of PA is that it can be seen as the result of an excessively female brain. Women are more likely than men to be co-dependents and have eating disorders. Girls are more compliant than boys, better behaved, and more eager to please. They are better able to figure out the needs of others. They are politically more “liberal,” and more likely to think that an important function of government is taking care of people. Low levels of testosterone in the womb during fetal development is associated with higher levels of empathy in both sexes.

PA may be the mirror image of autism, which is far more common in boys than in girls, and is characterized by an inability to sense the feelings of others. One author speculates that there are probably as many female pathological altruists as there are males with autism.

There are parts of the brain that light up and signal sympathy when we see people in pain or being punished. Psychological studies have been set up in which the brains of subjects were scanned while they watched the punishment of people who had cheated in a game. The sympathy circuits in women’s brains lit up; those in men did not. Men appear to lose their instinctive sympathy for pain when they think it is deserved; women remain sympathetic.

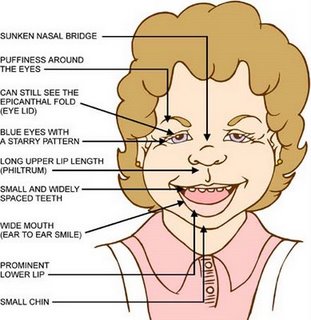

There is very strong evidence that altruistic behavior is under genetic control. The genetic abnormality known as Williams Syndrome has been called “the pathology of overfriendliness,” and people who suffer from it are excessively trusting and sympathetic. They are somewhat retarded and easily become victims of sexual abuse. They have abnormalities in the part of the brain known as the amygdala, which is involved in reading facial expressions and assessing threats. They are perhaps the only known group of people who show no racial bias.

The amygdala, anterior temporal cortex, and insula are parts of the brain involved in sensing the pain of others. Psychopaths have less brain matter in these locations than normal people, and it may be that people with more brain matter in these areas have a tendency towards PA.

The neurotransmitter serotonin appears to alter moral judgment, making people less willing to offend others, while oxytocin increases sociability and trusting — within the group. According to one study, oxytocin makes people more likely to sacrifice for their in-group and oppose those in the out-group. The genes known as DRD4, IGF2, and DRD5 have been associated with altruism and selflessness. As one of the contributors notes, “It seems safe to conclude, then, that traits behind costly altruistic behaviors are under a substantial biological influence that manifests itself through a variety of neurohormonal pathways and mechanisms that have only just begun to be understood.”

Addictive States of Mind

Altruism is also linked to the limbic system, meaning that doing good is related to the brain’s system of rewarding itself. When people are generous, they get the same kind of pleasurable jolt as from music, sex, exercise, and performing a skill. Psychic self reward of this kind is normal. It appears, however, that some people become addicted to the sensation of altruism. This is the kind of person who throws himself into self sacrifice, sainthood, or martyrdom.

Two of the most fascinating chapters in this book describe the way the brain thrives on self-righteousness and the conviction of being in the right. Contributor Robert A. Burton of the UC San Francisco Medical Center issues a warning that is worth quoting at length:

Despite the fact that a moral conviction feels like a deliberate rational conclusion to a particular line of reasoning, it is neither a conscious choice nor a thought process. Certainty and similar states of ‘knowing that we know’ arise out of primary brain mechanisms that, like love or anger, function independently of rationality or reason . . . .

What feels like a conscious life-affirming moral choice — my life will have meaning if I help others — will be greatly influenced by the strength of an unconscious and involuntary mental sensation that tells me that this decision is “correct.” It will be this same feeling that will tell you the “rightness” of giving food to starving children in Somalia, doing every medical test imaginable on a clearly terminal patient, or bombing an Israeli school bus. It helps to see this feeling of knowing as analogous to other bodily sensations over which we have no direct control.

In other words, just because you are convinced something is right does not make it right. The sensations of rightness and nobility are so pleasurable that people are inclined to seek them for their own sakes, and without regard to facts or consequences. Dr. Burton continues:

Talk to an insistent know-it-all who refuses to consider contrary opinions and you get a palpable sense of how the feeling of knowing can create a mental state akin to addiction . . . . [I]magine the profound effect of feeling certain that you have ultimate answers . . . . Relinquishing such strongly felt personal beliefs would require undoing or lessening major connections with the overwhelmingly seductive pleasure-reward circuitry. Think of such a shift of opinion as producing the same type of physiological changes as withdrawing from drugs, alcohol, or cigarettes.

Science writer and novelist David Brin writes about the same thing, noting that “dogmatic self-righteousness is often an ‘addiction’.” He adds that “sanctimony, or a sense of righteous outrage, can feel so intense and delicious that many people actively seek to return to it, again and again.” He calls this need to stimulate the brain with self righteousness “self doping,” and defines it as follows:

The pleasure of knowing, with subjective certainty, that you are right and your opponents are deeply, despicably wrong. Or, that your method of helping others is so purely motivated and correct that all criticism can be dismissed with a shrug, along with any contradicting evidence.

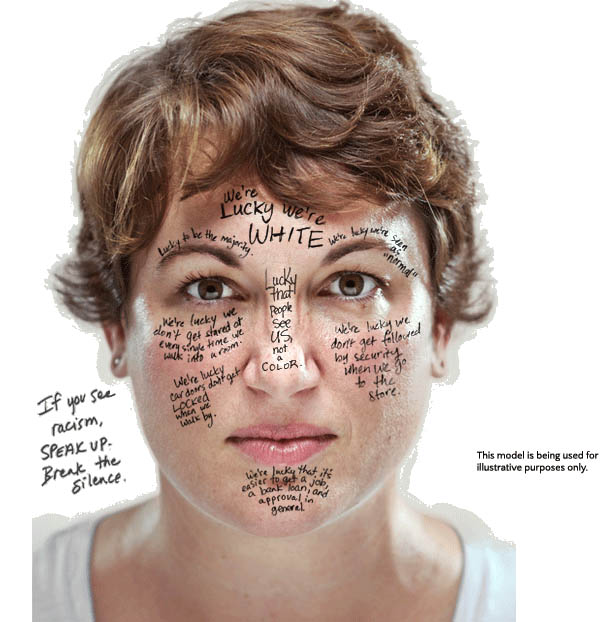

This is the kind of conviction that can lead to acts of altruism that are clearly pathological. At the same time, whether these authors know it or not, they have painted a vivid portrait of the mental state of anti-racism and of the motives that drive it. In the West, there is nothing that offers more ecstatic self-righteousness than denouncing “racism.”

In past ages, there have been different ways to gorge on blinkered, hateful, joyous denunciation: Religious fanatics burned heretics, commissars executed kulaks, Muslims beheaded apostates (and still do). Today, liberals hate “racists” — and “homophobes” and “sexists” and “fascists” — with the same Old Testament hatred. They are so drunk on self-righteous denunciation they are impervious to reality. Religion has not declined in the West; it has only taken new forms. Communism was religion for Communists, and liberalism is religion for liberals.

Of course, people at all points of the political spectrum can hold self-righteous beliefs in direct contradiction to the facts. As Dr. Brin points out, scientists get interesting results when they use committed Democrats or Republicans as test subjects. They have them watch a persuasive presentation that argues against their beliefs, and monitor their brains to see how they react. The parts of the brain involved in normal, logical reasoning are not active. Instead, the brain reverts to the equivalent of sucking its thumb, with reward circuitry firing away, just like an addict getting a shot of cocaine. Strong conviction seems to turn off the brain’s logic circuits.

This effect is especially strong in the case of altruism, because people both “self dope” with it and win the praise of others. One chapter raises the question of whether most foreign aid is not PA, especially the kind practiced by celebrities. The singer Madonna claims she wants to “literally transform the future of an entire generation.” Bill Clinton says, “There’s a whole world out there that needs you, down the street or across the ocean. Give.” Bill and Melinda Gates, along with Warren buffet, are other showy examples of what could be called “philanthrocapitalism.”

Over a trillion dollars have been sunk into black Africa since 1960, with not much to show for it. Why do people keep giving? As this chapter explains, people get a huge psychological boost from administering aid: “While charity has a mixed record helping others, it has an almost perfect record of helping ourselves.” The authors note that “staring at pictures of starving children can, in some sense, hijack the analytical portions of the brain,” resulting in “altruism” that is nothing short of crazy. After the 2004 tsunami did so much damage in South Asia, “altruists” sent Viagra, Santa suits, high-heeled shoes, evening gowns, and loads of other junk. After an earthquake in Pakistan, Westerners sent so much completely inappropriate clothing that people burned it to stay warm.

Journalist Linda Polman has pointed out that foreign aid can even provoke atrocities. Warring gangs in Africa or elsewhere know that bounty follows headlines, so they do something especially horrible and wait for truckloads of relief to show up — which they steal. The leaders of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone made a name for themselves in the late 1990s by cutting off the arms of women and children. The RUF’s leaders knew this would bring caravans of booty.

The authors of this chapter note that poorly thought out foreign aid has repeatedly had disastrous effects. They suggest that if aid is to continue, it should be run by engineers, not the current glory seekers.

Some of the authors in this book argue that there is no such thing as genuinely disinterested altruism, and that even the most seemingly generous acts are self serving. Mother Theresa may have been a “saint,” but she was just doing what she wanted to do. In the case of government foreign aid and non-profits, the people who ladle out uplift and bask in praise are not even spending their own money.

Altruism and Groups

Some of the chapters in this book touch on group differences. Dr. Brin notes that glorifying altruism is both recent and Western. He believes that a society must have a certain level of material wealth before it can value certain kinds of altruism. Only when people have enough to eat do they shift “from predation to inclusion” and think about animal rights rather than the next rabbit dinner. He points out that only Europeans have decided “to elevate altruism above other culturally promoted ideals, such as tribal patriotism and glory-at-arms, which our ancestors considered paramount.” They have gone even further, extending tribal altruism to the entire world, though “some other cultures consider this Western quality to border on madness.” Of course, it is madness, but Europeans who point this out are punished.

Some preliminary research suggests that people of different ethnicities and religions have different levels of guilt and show different levels of altruism. No doubt what is considered normal social behavior in one culture may be seen as extreme self-sacrifice in another. When Koreans and Americans act altruistically different parts of the brain appear to be involved. Could this also be true for Koreans adopted as children and reared in America?

A few of the contributors write about “parochial altruism,” or self-destructive acts that are meant to benefit one’s own group by harming another group. The clearest example of this is suicide bombers, who die in order to advance the cause of their people. The authors recognize suicide attacks as “a rational option when a weak insurgent group is opposing a very powerful group.” They are high-value missions in a war that some combatants are prepared to fight with any means available.

This is one form of altruism that is overwhelmingly male; scholars find that only about 20 percent of suicide bombers are women. Aside from sex, biographical reconstructions of successful bombers and interviews with captured bombers show that aside from high altruism and devotion to a cause, they fit no profile and come from all walks of life.

Some of the contributors to this volume recognize that in-group loyalty is part of human nature, but they worry about it leading to persecution of outsiders and wish it would go away. As one argues:

[D]efection from local in-groups is the highest form of altruism. Humanity as a whole might benefit the most if individuals made no sacrifices for their local group.

This is precisely the thinking that leads to oblivion: We will turn our backs on our own group in the hope that members of other groups will do the same — despite clear evidence that other groups have no such intention.

A somewhat less deceived writer advises that if groups want to act altruistically towards other groups they should at least look for groups that follow the same rules. But that is as far as this book goes. Group-level pathology leads only to mistreatment of out-groups. Apparently none of the authors can conceive of pathology in which the in-group mistreats itself for the benefit of strangers. Perhaps this blindness was inevitable in the times in which we live.

For the most part, however, this book is comprehensive and even bold, but there are other lapses. The first example of pathological altruism, which appears on the first page of the first chapter, is the Buck v. Bell Supreme Court decision in which Oliver Wendell Holmes justified forcible sterilization because “society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.” Adolf Hitler appears in the next sentence.

There is also a chapter on something called “therapeutic jurisprudence” that claims courts should heal and affirm and never humiliate people. This is also a mercifully short chapter by the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi that says nothing. These are rare exceptions. This is an insightful, provocative, beautifully edited book that will teach you a great deal you did not know.