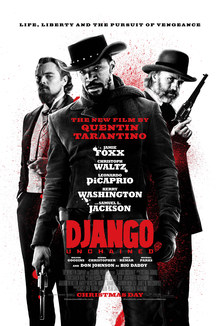

Should White People Watch Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained?

Jon Harrison Sims, American Renaissance, January 11, 2013

Django Unchained (2012), Written and Directed by Quentin Tarantino, Starring Jamie Foxx, Leonardo DiCaprio, Christoph Waltz, Samuel L. Jackson, 2 hours, 45 minutes.

American whites have long believed that the price of peace was just one more concession. If anything disabuses them of this naïve notion, the critical acclaim for Quentin Tarantino’s new black-revenge fantasy should do so.

In a December 8 appearance on “Saturday Night Live,” the lead actor, Jamie Foxx, explained what the movie is about:

It’s good to be black. Black is the new white. In my new movie, I play a slave. How black is that? I have to wear chains. How whack is that? I get free. I save my wife, and I kill all the white people in the movie. How great is that? And how black is that?”

The crowd erupted in laughter, whooping, and applause.

In 2009, Mr. Foxx apologized after calling Miley Cyrus, the pop singer, a “little white bitch,” but he has yet to apologize for telling us how much he enjoyed killing whites onscreen.

What this means is clear enough — whites are a problem that must be solved — but first I will turn to a different aspect of this film: it’s falsification of the past.

Rewriting the Past

When I was in graduate school, a professor repeatedly complained about the Right’s efforts to construct a “usable past.” Like most college professors, he was a leftist, and like all leftists, he practiced the very thing he condemned. His lectures were full of “lessons” about how the Republican Party’s view of the American past was fantastical, while the Democratic Party’s view of it — as racist, imperialist, sexist — was completely correct.

Django Unchained’s picture of the American past is as false and distorted as it is clearly “usable” for political purposes. Consider the implausible premise: a German bounty hunter in pre-Civil War Texas happens also to be an anti-slavery fanatic of the John Brown type. He needs the help of a slave, Django (Jamie Foxx), to identify two slave overseers — the Brittle brothers — who are wanted, “dead or alive.” The bounty hunter, Dr. King Schultz (Christopher Walz), prefers to bring them in dead.

Shultz finds Django among a gang of chained slaves being transported by two slave traders. He murders them, frees the slaves, and asks Django to help him find his quarry. After tracking and killing the Brittle brothers, the two strike a deal: If Django helps Schultz bounty-hunt through the winter, Schultz will help Django find and free his wife, who is a slave on a plantation in the Deep South.

Writer-director Quentin Tarantino in Paris at the French premiere of Django Unchained in January of 2013. (Credit Image: Georges Biard via Wikipedia)

One need not be an historian to see how fanciful all this is. First, by murdering the slave traders and freeing the slaves, Dr. Schultz would himself become a wanted man with a bounty on his head. The news of an armed and murderous abolitionist at large would bring out many posses determined to arrest this threat to private property and public order.

Second, how would a slave have acquired the skills (horsemanship, marksmanship, tracking, woodcraft) needed to be a bounty hunter? Schultz would have no reason to be partners with Django. He would be far more likely to sell him back into slavery after the black had helped him identify the two Brittle brothers. After all, Schultz is a bounty hunter.

After a winter of killing white people, Schultz and his protégé find Django’s wife, Broomhilda, enslaved on a Mississippi plantation named Candieland, after the loathsome Calvin J. Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio). Broomhilda has been beaten for trying to escape and — it is strongly suggested — raped as well.

Mr. Tarantino’s Candie is, as one reviewer put it, “the embodiment of racist evil.” He is a sadist, a kind of racist Marquis de Sade. He enjoys watching one of his aging slaves torn to death by a pack of ferocious dogs, but his favorite amusement is “mandingo fighting,” in which two slaves are tethered together by a rope and forced to fight to the death. We get to watch the graphic spectacle on screen.

Django Unchained: Leonardo DiCaprio as Calvin Candie. (Credit: © Columbia Pictures / Entertainment Pictures / ZUMAPRESS.com)

To infiltrate the plantation, Schultz and Django pose as “mandingo traders.” They then kill all the whites.

“Fuck the facts”

There was no “mandingo fighting” in the Old South, and slave owners did not dispatch old slaves by feeding them to their dogs, yet this matters not at all to Mr. Tarantino or most of the movie reviewers. They seem to regard these fabrications as serving the higher purpose of demonizing white people. Not all the reviewers are as direct as the Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers who says, simply, “Fuck the facts,” but they all take a similar view. Simultaneously and contradictorily, they claim that the movie is really truthful after all. Not one reviewer I am aware of mentioned Mr. Foxx’s remarks on “Saturday Night Live.”

The USA Today’s Claudia Puig calls Tarantino’s “reimagining of history” “dazzling, daring, gruesome, and astonishingly funny.” She also believes it serves the worthy purpose of “driv[ing] home the ugliness of racism.” “Tarantino has something serious to say about American culture, history, and race.” She does not say what that “something” is, nor just what was so “astonishingly funny.”

The New York Times’ A.O. Scott calls the movie “brazenly irresponsible but also ethically serious,” “a wild and bloody live action cartoon,” but “also a troubling and important movie about slavery and racism.” Clearly Mr. Scott likes having it both ways.

NPR’s Stephanie Zacharek calls the movie an “antibigotry neo-Spaghetti Western exploitation comedy.” Murdering white people is great comedy. But the movie is also instructive in that it reminds us that “old ideas of inferiority still linger.” Miss Zacharek tells us that “if it takes significant liberties with history . . . it also faces certain historical truths head-on.” Like what? That the “N-word” used to be in widespread use, even in polite circles. She is wrong. “Nigger” was considered a crude word even in the Old South, and was not acceptable in polite company.

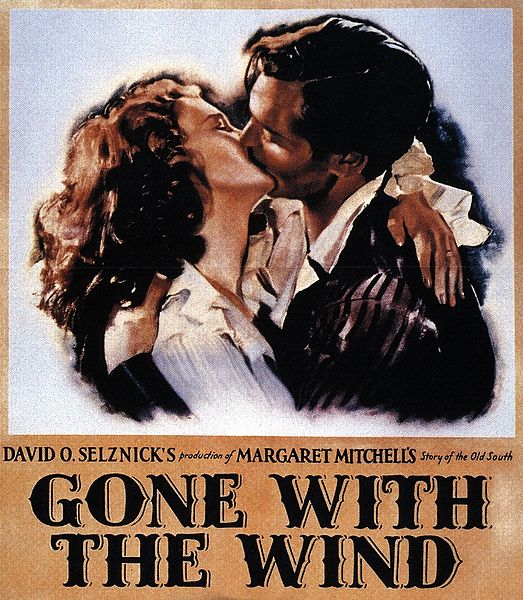

The Washington Post’s Ann Hornaday writes, with no awareness of contradiction, of the film’s “admittedly exaggerated but brutally vivid truths.” “Sure, this is an outrageous distortion,” she admits, but argues that the movie is no less a distortion than Gone with the Wind. As a historian, I know something about Southern plantation life, and I can assure readers that Margaret Mitchell’s Tara, with all its romanticism, is far closer to the real thing than Tarantino’s torture chamber.

In defense of Django Unchained’s falsifications, Miss Hornaday goes on to call it “far more prudent in its license taking” than Abraham Lincoln — Vampire Hunter. Abraham Lincoln — Vampire Hunter? It is faint praise, indeed, to say a movie is more realistic than one in which the 16th President puts down a band of vampires who are trying to take over the country.

The pseudo-right-wing Wall Street Journal’s Joe Morgenstern showers the film with florid adjectives, “wildly extravagant, ferociously violent, ludicrously lurid and outrageously entertaining, yet also . . . very much about the pernicious lunacy of racism, and yes, slavery’s singular horrors.”

One reviewer, Richard Corliss of Time, mentions Django’s reply when Schultz ask him to be his partner: “Kill white folks and they pay you for it? What’s not to like?” Mr. Corliss calls this “a tantalizing question.” Let us imagine a movie by Mel Gibson, say, in which someone is offered money to assassinate leftwing media types. Would he still think “What’s not to like?” was a “a tantalizing question?” Or would he wail in print about the murderous hatreds of the American Right?

A few critics understood exactly what the movie is about — and loved it. Mike Lasalle of the San Franciso Chronicle titled his review “Sweet Revenge,” and exults that “there’s a place for violence onscreen, and this is the place.” Claudia Puigg of USA Today tells us Mr. Tarantino “offers an empowering alternate vision” of American history. Empowering to whom? Blacks who hate whites. Richard Corliss of Time says that Tarantino “frees a black man to take revenge for two centuries of racial humiliation.” And A.O. Scott of the New York Times notes that Mr. Tarantino “takes homicidal vengeance as the highest, if not the only, form of justice.”

Joe Williams of the St. Louis Post Dispatch has the mildest view of “the purpose” of the movie: It is “about cleansing the stain on the American soul.” I thought we had already done that with over 600,000 almost exclusively white fatalities during the Civil War, Martin Luther King Day, Black History Month, a black president . . . but never mind.

Perhaps most irritating are people like the Washington Post’s Ann Hornaday who say the movie is “meaningfully engaging the history it’s repurposing.” First of all, “repurposing” history means creating a usable past. But it is certainly not “engaging history.” Mr. Tarantino’s film is not about history and it is not about slavery. It is about racial revenge. That is its only subject, and the reviewers welcome it.

There had been some worry in movie industry circles that constant talk of “niggers” — someone reported that the word was used 110 times — would offend blacks and keep them out of theaters. Spike Lee urged a boycott.

But blacks are lapping up Django. According to The Hollywood Reporter, 42 percent of the opening day audience was black, and since then 30 percent of the viewers have been black. As Steve Sailor has noted, a black posted a comment about the movie:

While whites are busy getting offended on our behalf, they miss completely why we are going to see this film. It’s a black man killing white people in masses. I will pay to see that every time.

I’ve seen this film 3 times so far and am going again Saturday night. It’s an awesome movie.

“Awesome” is another way of saying “inspiring.”

Twitchy.com, which tracks twitter messages, found this sort of thing:

“After watching Django, all I wanna do is shoot white people.”

“Still hype off Django. I’m gonna kill some white people today.”

“Django got me wanting to kill white people!”

“Django made me wanna kill so many white people.”

Mr. Tarantino appears to have gotten his wish. In a recent interview, he said he made the movie because he wanted “to give black American males a western hero, give them a cool, folkloric hero that could actually be empowering and pay back blood for blood.” He seems to find no irony in the idea of a white director giving blacks a hero, nor any harm in encouraging revenge fantasies.

Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam said he thought the movie was “preparation for race war.”

Only one movie critic, Dana Stevens of Slate, expressed uneasiness about the film’s “unleashing of gleefully gory racial retribution:” “Tarantino’s intent may have been to showcase the horrors of slavery, but there is something about his directorial delectation in all these acts of racial violence that left me not just physically but morally queasy.” Miss Stevens is the only reviewer I’ve read who appears to have a conscience.

Another reviewer with some reservations is the New Yorker’s Anthony Lane who admits that he was “disturbed by their [Tarantino’s fans] yelps of triumphant laughter, at the screening I attended, as a white woman was blown away by Django’s guns.” Mr. Lane does not mention the race of the viewers.

To the other reviewers, I have this to say: Whites have grievances too, not the least of which is being turned into a minority in our own country by trickery and coercion, forced racial busing, as well as non-white quotas, refugee resettlement, affirmative action for immigrants, blacklists of paleoconservatives, and 30 years of censorship of those who oppose the Left’s anti-white policies. Two can play the game of revenge. Richard Corliss and A.O. Scott would do well to reflect on these things.