Race, Nation and the Soldier: Wellington’s Secret Weapon

Steven Schwamenfeld, American Renaissance, April 1997

What accounts for the extraordinary expansion of British power in the 18th and 19th centuries? Most “respectable” academics offer economic reasons for British success against European powers, and take the view that Western technological superiority accounts for colonial expansion. My study of the British army of the Napoleonic era suggests a different explanation: the moral power of the British soldier, as manifested in his devotion to his regiment, to his nation and — when he was fighting colonial wars — to his race. Patriotic conviction together with contempt for foreigners made the average British soldier the best in the world.

Duke of Wellington

The Invincible Duke

The British army under the command of the Duke of Wellington won 15 general engagements between 1808 and 1815 without suffering a single defeat. Its victories shattered the myth of French invincibility and inspired the resistance of the other European nations.

The most sincere assessment of British arms came from the enemy. The French marshal Nicolas Soult described the victors after his defeat at Albuera in 1811 with rueful sarcasm: “[T]here is no beating these troops in spite of their generals. I always thought they were bad soldiers; now I am sure of it. I had turned their right, pierced their center and everywhere victory was mine, but they did not know how to run.” Another French observers, General Chambray, praised the British infantry for its “orderliness, impetus and resolution to fight with the bayonet.”

A Prussian observer left this description of Wellington’s army:

For a battle, there is not perhaps in Europe an army equal to the British, that is to say none whose tuition, discipline, and whole military tendency, is so purely and exclusively calculated to giving battle. The British soldier is vigorous, well-fed, by nature highly brave and intrepid, trained to the most rigorous discipline and admirably well-armed. The infantry resist the attack of cavalry with great confidence, and when taken in the flank or rear, British troops are less disconcerted than any other European Army.

Although it is the Duke of Wellington’s forces that are of particular interest to us here, the British infantry had long been redoubtable, and maintained its prowess well after the Iron Duke’s day. A Spanish chronicler, writing in 1486, left us this description of a force of English bowmen:

This cavalier was from the island of England and brought with him a train of his vassals, men who had been hardened in certain civil wars which had raged in their country . . . They were withal of great pride, but it was not like our own inflammable Spanish pride . . . [T]heir pride was silent and contumelious. Though from a remote and somewhat barbarous island, they yet believed themselves the most perfect men on earth . . . With all this, it must be said of them that they were marvelous good men in the field, dexterous archers and powerful with the battleaxe. In their great pride and self-will, they always sought to press in their advantage and take the post of danger . . . They did not rush forward fiercely, or make a brilliant onset, like the Moorish and Spanish troops, but went into the fight deliberately and persisted obstinately and were slow to find out when they were beaten.

Likewise, in 1854, two years after Wellington’s death, the armies he had commanded were still an astonishing force. The battle of Alma, during the Crimean War, gave rise to this first-hand account:

. . . the Grenadiers and Coldstreamers [and Scots Guards], though under a deadly fire, formed into line with as much precision and lack of hurry as if they had been on the parade ground, and began deliberately to advance up the glacis toward the Great Redoubt.

It was an unforgettable sight. The men marched as if they were taking part in a review. Storm after storm of bullets, grape, shrapnel, and round shot tore through them, man after man fell, but the pace never altered, the line closed in and continued, ‘ceremoniously and with dignity,’ as an eyewitness wrote, on its way . . . The Guards marched into the Great Redoubt, and there was a shout of triumph so loud that William Howard Russell [correspondent for The Times] heard it on the opposite bank — the battle of the Alma had been won.

A French officer turned to [British Colonel] Evelyn Wood . . . ‘Our men could not have done it,’ he said.

How were the British capable of such feats of arms? It was partially the result of intense training.

The 2nd Rifle Brigade leads the Light Division across the river during the Battle of the Alma on September 20, 1854, during the Crimean War.

The great French military theorist Baron de Jomini believed only British troops were adequately trained to fight in a thin, two-deep battle line. It required a maximum of discipline to maneuver in this unwieldy formation; less trained troops required a deeper formation to maintain cohesion.

In addition, British troops displayed a tremendous corporate loyalty, not only to their regiments but to their nation. Almost alone among the armies of the 17th and 18th centuries, the British army possessed no permanent mercenary units. It was always a national force. As the historian of 18th century warfare, Christopher Duffy, writes: “the most pronounced moral traits of the English were violence and patriotism . . . All classes were united in their contempt for foreigners.” It was this ferocious patriotism that helped breed, in Samuel Johnson’s words, “a peasantry of heroes.”

The uniquely nationalist sentiment of the English soldier dates back long into the past. To quote historian Linda Colley: “a popular sense of Englishness . . . considerably predates the French Revolution.” An Italian visitor to England in 1548 described his hosts thus: “the English are commonly destitute of good breeding, and are despisers of foreigners, since they esteem him a wretched being and but half a man who may be born elsewhere than in Britain.” This was true not only of the aristocracy but of the common people as well. It was especially true of bowmen. They were of peasant stock but, in the words of the 15th century jurist, Sir John Fortescue, who fought at their side, they were the men whom “the might of the realm of England standyth upon.”

The English archers of the Middle Ages left no memoirs about their contempt for foreigners, but their successors in Wellington’s time did.

Here is Private William Wheeler of the 51st Light Infantry on Britain’s allies during the Peninsular War (1808-1814):

What an ignorant, superstitious, priest-ridden, dirty, lousy set of poor devils are the Portuguese. Without seeing them it is impossible to conceive there exists a people in Europe so debased. The filthiest pigsty is a palace to the filthy houses in this dirty stinking city [Lisbon], all the dirt made in the houses is thrown into the streets, where it remains baking until a storm of rain washes it away. The streets are crowded with half-starved dogs, fat Priests and lousy people. The dogs should all be destroyed, the able-bodied Priests drafted into the Army, half the remainder should be made to keep the city clean, and the remainder if they did not inculcate the necessity of personal cleanliness should be hanged.

Sgt. John Cooper of the 7th Fusiliers was no more complimentary about Spaniards: “The lower orders of this nation are dirty in their persons, filthy in their habits, obscene in their language, and vindictive in their tempers. Their houses are intolerably smoky and vermin abound.”

Observations such as these are to be found throughout soldiers’ memoirs. About the military prowess of their Iberian allies, Sgt. William Lawrence of the 40th wrote: “the smell of powder often seemed to cause them to be missing when wanted.” Sgt. William Surtees of the 95th Rifles recalled the Duke of Wellington’s jest about a Spanish division fleeing the field from the Battle of Toulouse in 1814; Wellington “wondered whether the Pyrenees would bring them up again, they seemed to have got such a fright.” Surtees asserted that the Duke “did not indeed depend on their valour, or he would have made a bad winding up of his Peninsular campaign.”

On first viewing a Spanish army, Sgt. Andrew Pearson of the 61st recalled: “Falstaff’s ragged regiment would have done honour to any force compared to the men before us.” Surtees described the Spanish officer corps thus:

In short, they had all the pride, arrogance, and self-sufficiency of the best officers in the world, with the very least of all pretensions to have an high opinion of themselves; it is true they were not all alike, but the majority of them were the most haughty, and at the same time most contemptible creatures in the shape of officers, that I ever beheld.

The British had an entirely different view of their own superiors. Rifleman John Harris of the 95th wrote this of his Brigadier, William Beresford:

He was equal to his business, too, I would say; and he amongst others of our generals, often made me think that the French army had nothing to show in the shape of officers who could at all compare to ours. There was a noble bearing in our leaders, which they, on the French side (as far as I was capable of observing) had not; . . . They are a strange set, the English! and so determined and unconquerable, that they will have their way if they can. Indeed, it requires one who has authority in his face, as well as at his back, to make them respect and obey him.

Harris frankly believed that the British aristocracy produced the finest leaders of men in the world.

Britain was very much a class society, but in battle the shared characteristics of courage, stoicism and perseverance united all. Thomas Howell, of the 71st Highlanders, was a man of some gentility, who joined the army as a private as a result of financial disaster. He had a difficult time adjusting to life among men of a lower class. However, he left this moving account of his rough-hewn comrades during his first battle with the French:

In our first charge I felt my mind waver, a breathless sensation came over me. The silence was appalling. I looked alongst the line. It was enough to assure me. The steady, determined scowl of my companions assured my heart and gave me determination. How unlike the noisy advance of the French!

During the Peninsular War, the British had a far higher regard for their enemy than for their allies. They found the French to be brave, if erratic, soldiers and generally chivalrous. One of the few really negative descriptions comes from Sgt. Edward Costello of the 95th Rifles, and it is a condemnation of only a specific group of men rather than of the French nation. It casts light on those qualities that either impressed or revolted British soldiers.

After the capture of Ciudad Rodrigo in 1812, some French prisoners were present at the interment of British dead:

One more careless than the rest viewed the occurrence with a kind of malicious sneer, which so enraged our men that one of them, taking the little tawny-looking Italian by the nape of his neck, kicked his hind-quarters soundly for it. I could not, at the time, help remarking the very under-sized appearance of the Frenchmen. They were the ugliest set I ever saw, and seemed to be the refuse of their army, and looked more like Italians than Frenchmen.

Wellington’s men had a stoic pride that, in their minds, set them apart from men of any other nationality. A remarkable incident was recorded by Sgt. Edward Costello when he was recovering from a wound received at the Battle of Salamanca in July 1812. His hospital ward was under the charge of a fellow Irishman, Sgt. Michael Connelly:

Mike was exceedingly attentive to the sick, and particularly anxious that the British soldier, when dying, should hold out a pattern of firmness to the Frenchmen who lay intermixed with us in the same wards. ‘Hould your tongue, ye blathering devil,’ he would say in a low tone, ‘and don’t be after disgracing your country in the teeth of these ere furriners, by dying hard. Ye’ll have company at your burial, won’t you? Ye’ll have the drums beating and the guns firing over ye, won’t ye? . . . For God’s sake, die like a man before these ‘ere Frenchers.’

After Waterloo, Costello again found himself in hospital, this time in Brussels, and recorded something even more remarkable:

I remained in Brussels three days, and had ample means here, as in several other places, such as Salamanca, &c., for witnessing the cutting off of legs and arms. The French I have ever found to be brave, yet I cannot say they will undergo a surgical operation with the cool, unflinching spirit of a British soldier. An incident which came under my notice may in some measure show the differences of the two nations. An English soldier belonging to, if I recollect rightly, the 1st Royal Dragoons, evidently an old weather-beaten warfarer, while undergoing the amputation of an arm below the elbow, held the injured limb in his other hand without betraying the slightest emotion, save occasionally helping out his pain by spirting forth the proceeds of a large plug of tobacco, which he chewed most unmercifully while under the operation. Near to him was a Frenchman, bellowing lustily, while a surgeon was probing for a ball near the shoulder. This seemed to annoy the Englishman more than anything else, and so much so, that as soon as his arm was amputated, he struck the Frenchman a smart blow across the breech with the severed limb, holding it at the wrist, saying, ‘Here, take that, and stuff it down your throat, and stop your damn bellowing!’

The Colonial Campaigns

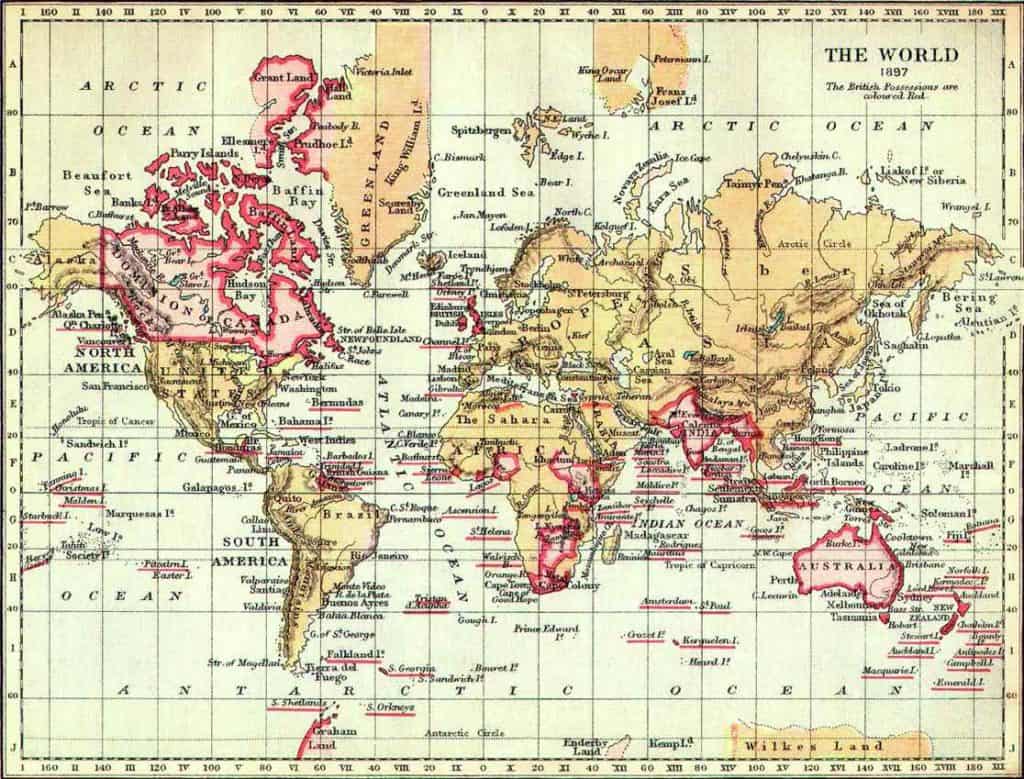

The British Empire in 1897.

Warfare against non-Europeans inspired a far greater sense of distance and alienness. John Shipp of the 87th, the only man of his era to win two commissions from the ranks, wrote of battle against the “Caffres” of South Africa:

At every farmhouse in our line of march we found appalling scenes of murder and desolation. Whole families had been massacred by these wild people, whose devastations it was now our duty to check. So ignorant were they, that I am convinced they were unaware that murder is a crime . . . The savage Caffre exults in these appalling sights. To his bestial mind the groans of the wounded, and the dying, are the greatest of pleasures. When the frenzy of the attack is on him he is wrought up to ecstasy, dancing and jumping about, and hauling spears at man or beast with reckless abandon . . . I have seen them with [murdered] women’s gowns, petticoats, shawls and things tied round their legs and between their toes, capering about the woods in a frenzy of delight.

Sgt. George Calladine of the 19th recalled his first encounter with Africans: “I certainly saw little naked children running about which, if I had seen nothing of them but their faces, I should have taken them for monkeys.” Sgt. Pearson wrote of the “Caffres” with more sympathy, marveling at their physiques: “six feet six inches to seven feet, with most symmetrical figures.”

William Richardson was a common seamen who served in the Royal Navy between 1793 and 1819. Before being impressed into the Navy he served on several merchant vessels, including a slaver. He recorded his impressions of the trade:

Some people in England think that we hunt and catch the slaves ourselves, but this is a mistaken idea, for we get them by barter as follows: their petty kings and traders get them not so much by wars (as is imagined) as by trade and treachery, and when they get a number for sale bring them to the coast and sell them . . . There was one of their petty kings who, when he came on board, would strut along the deck as if he had been one of the greatest men in the world: he was a little fat fellow dressed in a suit of coarse blue cloth edged with something like yellow worsted, but what spoiled all was that he had no shirt, shoes or stockings on, and his naked black feet and legs being dabbed over with mud and salt water, made him a laughingstock to the sailors; but did not put him out of conceit of himself.

Colonial wars were not confined to Africa. Thomas Howell of the 71st Highlanders recorded his none too flattering impressions of the Indians of Montevideo:

The native women were the most uncomely I ever beheld. They have broad noses, thick lips, and are of very small stature. Their hair, which is long, black and hard to the feel, they wear frizzled up in front in the most hideous manner, while it hangs down their backs below the waist. When they dress they stick in it feathers and flowers, and walk about in all the pride of ugliness. The men . . . are brave, but indolent to excess . . . As for their idleness, I have seen them lie stretched, for a whole day, gazing upon the river, and their wives bring them their victuals; and if they were not pleased with the quantity, they would beat them furiously. This is the only exertion they make willingly — venting their fury upon their wives.

These remarks concerning the physical characteristics of Africans and Indians (not to mention Latins) point to the British soldier’s racial consciousness as part of his patriotism. This is not to say that the British soldier loathed non-European foes because of race; it was because of the latter’s savagery. Sgt. James Thompson served with the 78th Highlanders at Quebec in 1759, during one of the North American campaigns of the Seven Years War. He witnessed the repulse of a British attack on the Ile d’Orleans: “When the French saw us far enough on the retreat, they sent their savages to scalp and tomahawk our poor fellows that lay wounded on the beach.”

During the War of 1812, British troops this time found themselves allied to Indians. Historian Donald Graves describes an event that took place after the Battle of Lundy’s Lane in 1814: “Sergeant Commins of the 8th and Private Byfield of the 41st watched with horror as an Indian ‘busy in plundering came to an American that had been severely wounded and not being able to get the man’s boots off threw him into the fire.’ A nearby British regular ‘filled with indignation for such barbarity shot the Indian and threw him onto the fire to suffer for his unprincipled villainy.’”

Sgt. William Lawrence of the 40th described a grisly encounter with Indians near Buenos Aires in 1807. A corporal and a private were killed while destroying native huts: “This was a great glory to the natives; they stuck the corporal’s head on a pole and carried it in front of their little band on the march.” Later: “As we marched along on our next day’s journey, about two hundred Indians kept following us, the foremost of them wearing our dead corporal’s jacket, and carrying his head — I do not know for what reason, but perhaps they thought a good deal more of a dead man’s head than we should feel disposed to do.”

Later the 200 Indians attacked Lawrence’s party of 20 infantrymen and were easily repulsed, they “not liking the smell and much less the taste of our gunpowder.” The Indian chief who carried the corporal’s head was wounded and captured by the British. He was not killed out of hand but was treated according to civilized custom and left with friendly Indians to be nursed back to health.

It did not take long for non-Europeans to discover and profit from the differences between British and native warfare. Sir Evelyn Wood writes of interrogating Zulu prisoners in 1879 after the battle of Kambula:

When I had obtained all the information I required I said, ‘Before Isandwhlana [an 1879 battle in which a Zulu army of 20,000 routed and massacred 800 encamped British infantry] we treated all your wounded men in our hospital. But when you attacked our camp your brethren, our black patients, rose and helped to kill those who had been attending on them. Can any of you advance any reason why I should not kill you?’ One of the younger men, with an intelligent face, asked, ‘May I speak?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘There is a very good reason why you should not kill us. We kill you because it is the custom of the black men [to kill prisoners]. But it isn’t the white man’s custom.’

The Englishman reportedly had no answer to this, and the blacks were later freed.

When it came to actual warfare against non-white armies, the popular conception is of an unfair contest with European colonial troops discharging advanced weaponry on natives armed with sticks and clubs. The truth was often quite different. In discussing Wellington’s great victory over a Mahratta (Indian) army six times the size of his own at Assaye in 1803, historian Jeremy Black points out that “success owed much to a bayonet charge, scarcely conforming to the standard image of Western armies gunning down masses of non-European troops relying on cold steel.” This contemporary historian refrains from analyzing how that small red-coated force achieved its moral triumph, and certainly does not discuss any patriotic or racialist motivations it may have possessed. The British commander knew better.

The Duke of Wellington is notorious for describing his infantry as the “scum of the earth.” Yet this was most of all a description of their social class and their vices (drink above all). In battle, the British soldier was “the item upon which victory depends.” On his return from India in 1804, Wellington wrote a memorandum in which he offered an explanation for the incredible achievements of the British, especially in India. It should be studied by all military “experts” who would deride the importance of national (and racial) feeling among soldiers:

The English soldiers are the main foundation of the British power in Asia. They are a body with habits, manners and qualities peculiar to them in the East Indies. Bravery is the characteristic of the British army in all quarters of the world; but no other quarter has afforded such striking examples of the existence of this quality in the soldiers as the East Indies. An instance of their misbehavior in the field has never been known; and particularly those who have been for some time in that country cannot be ordered upon any service, however dangerous or arduous, that they will not effect, not only with bravery, but a degree of skill not often witnessed in persons of their description in other parts of the world. I attribute these qualities, which are peculiar to them in the East Indies, to the distinctness of their class in that country from all others existing in it. They feel they are a distinct and superior class to the rest of the world which surrounds them; and their actions correspond with their high notions of their own superiority . . . Their weaknesses and vices, however repugnant to the feelings and prejudices of the Natives, are passed over in the contemplation of their excellent qualities as soldiers, of which no nation has hitherto given such extraordinary instances. These qualities are the foundation of the British strength in Asia, and of that opinion by which it is generally supposed that the British empire has been gained and upheld. These qualities show in what manner nations, consisting of millions, are governed by 30,000 strangers . . .

Thus it was through a sense of national superiority, of the white Briton as a being apart, that the British Empire was won and held. Years later, Wellington would state plainly (in a parliamentary debate on Asian Indian participation in the higher levels of the Civil Service): “That the white man has an influence [of a moral kind] which the black man has not.” Wellington would scarcely have been able to credit the notion that one day British governments would discourage racial feelings among their soldiers. He praised the racial arrangements in the Southern United States, and considered them essential if America’s liberal system of government was to survive.

An understanding of the role of race has not entirely died among the British. A ranker (a soldier holding a rank other than that of officer) of the Second World War has left us with an analysis of the motivations of his comrades in Burma. George MacDonald Fraser’s bluntly honest account (put to paper in 1992) should ring as a battle cry for anyone interested in his own nation’s defense:

There is much talk today of guilt as an aftermath of wars — guilt over killing the enemy, and even guilt for surviving. Much depends on the circumstances, but I doubt if many of the Fourteenth Army lose much sleep over dead Japanese. For one thing they were a no-surrender enemy and if we hadn’t killed them they would surely have killed us. But there was more to it than that. It may appall a generation who have been dragooned into considering racism the ultimate crime, but I believe there was a feeling (there was in me) that the Jap was farther down the human scale than the European. It is a feeling that I see reflected today in institutions and people who would deny hotly that they are subconscious racists — the presence of TV cameras ensured a superficial concern for the Kurdish refugees and Bangladeshi flood victims, but we all know that the Western reaction would have been immeasurably greater if a similar disaster had occurred in Australia or Canada or Europe; some people seem to count more than others, with liberals as well as reactionaries, and it is folly to feel that racial kinship and likeness are not at the bottom of it.

A measured statement such as this would not be tolerated in America, and this bodes ill for the future, especially the future of our armed forces. As long as the basic principle of racial kinship is denied by our leaders, America’s very existence will be in peril. There can be no stability in a society which will not allow its members to favor their own brethren. An army that will deny its soldiers this right is an army on the road to defeat.

[Editor’s Note: This essay is in A Race Against Time: Racial Heresies for the 21st Century, a collection of some of the finest essays and reviews published by American Renaissance. It is available for purchase here.]