Some Thoughts are Worse Than Murder

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, August 2000

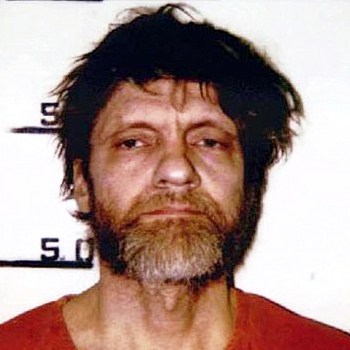

The cover story of the June issue of Atlantic Monthly is a long article about the life and motives of Theodore Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber. This sympathetic, detailed investigation of the career of a serial killer is interesting enough in its own right, but the unintentional light it casts on the political prejudices of our times is even more interesting.

The basic facts about Mr. Kaczynski are these: He was born in 1942 and grew up in the Chicago area. He was something of a loner but was a brilliant student who enrolled at Harvard at age sixteen. He went on to get a Ph.D. in math at the University of Michigan in 1967, and taught briefly at Berkeley. In 1971 he fled civilization to live in the Montana wilderness, and in 1978 began sending bombs to people he thought were promoting technology and industry. He sent at least 16 bombs, which killed three people and seriously injured two. By 1996 he was so notorious that the New York Times and the Washington Post agreed to publish copies of a 35,000-word essay he called “Industrial Society and Its Future,” which became known as The Manifesto. His brother recognized the thinking in the essay and alerted the police, who arrested Mr. Kaczynski. In May 1998, a California court sentenced him to life in prison without parole.

People have called The Manifesto everything from proof of insanity to the work of a genius. In fact, as the Atlantic author Alston Chase points out, it is essentially an elaboration on a leftist cliché that many people find attractive. “The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race,” begins The Manifesto, which goes on to argue that technology poisons society because it forces men to conform to machines rather than the other way around. Increasing industrialization will eventually strangle every human freedom but it cannot be stopped — short of violence — because “while technological progress AS A WHOLE continually narrows our sphere of freedom, each new technical advance CONSIDERED BY ITSELF appears to be desirable.” Mr. Kaczynski argued that since technology threatens mankind’s very survival, those who push it forward must be killed.

Mr. Chase reports that when The Manifesto was published, it met with much admiration on the left. Cynthia Ozick wrote in The New Yorker that the bomber was “a philosophical criminal of exceptional intelligence and humanitarian purpose, who is driven to commit murder out of an uncompromising idealism.” Robert Wright wrote in Time that “there’s a little bit of the Unabomber in most of us.” Kirkpatrick Sale wrote in the New York Times that the Unabomber’s views were “if hardly mainstream, entirely reasonable.”

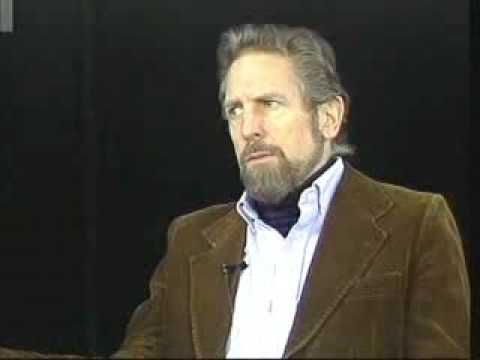

Kirkpatrick Sale

Mr. Kaczynski’s defense lawyers tried to argue that their client was insane, and Mr. Chase writes that the media quickly seconded this view — but out of sympathy rather than horror. He suggests in his article that “the public wished to see Kaczynski as insane because his ideas are too extreme for us to contemplate without discomfort. He challenges our most cherished beliefs.”

The Unabomber, Mr. Chase concludes, was: “evil. But what kind of evil?” It is the search for what appears to be an understandable, perhaps even admirable sort of evil that takes up most of the article: stories from Mr. Kaczynski’s childhood and a lengthy account of how Harvard must have formed his thinking. The bomber emerges as a brilliant, sincere, slightly off-balance intellectual who jumped the tracks and took his essentially rational thinking too far.

What a contrast to the way America treats those who deviate from racial orthodoxy! Dissidence alone, without even a hint of violence, is enough to cast the likes of Arthur Jensen, Philippe Rushton, Michael Levin, William Shockley, Samuel Francis, and Glayde Whitney into the outer darkness. They don’t have to throw bombs. They have only to express their views — certainly as eloquently as anything in The Manifesto — to be hectored, hounded, harassed, and even fired.

Needless to say, Atlantic will never devote a long article to trying to understand why they hold the views they do, despite the apparent fascination for a killer who “challenges our most cherished beliefs” and the admission that “there’s a little bit of the Unabomber in most of us.” There is no praise of this kind for “racists,” even though they certainly challenge cherished beliefs and only make explicit the racial rules even liberals live by. When will an Atlantic author ever concede that, indeed, he doesn’t want to live in a Mexican neighborhood or have his children marry blacks, and that “there’s a little David Duke in most of us”? No, the prevailing structure of taboos permits a sympathetic understanding even of murderers if they kill for causes that conform to that structure, but reserves nothing but stony condemnation for those who dissent.

David Duke speaks with reporters on election eve in 1990 in Metairie, Louisiana at his campaign headquarters. (Credit Image: © Jerry Mennenga / ZUMA Wire)

An enlightening contrast to the Atlantic piece appeared at about the same time in a review of The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach in the June 9 issue of National Review. Brasillach was a French poet and novelist who was called up for military service in 1938, fought the Germans, and was captured in June, 1940. His captors discovered that he was a fascist sympathizer, and he became a journalist for the Vichy government. After the liberation of Paris, before the war was even over, De Gaulle’s men arrested Brasillach, gave him a six-hour trial, condemned him to death, and shot him. Brasillach, like Mr. Kaczynski, was an intellectual, a writer of manifestos, but he never murdered anyone or encouraged others to kill. Unlike Mr. Kaczynski he is not worthy of sympathetic understanding because, according to contemporary standards, he cannot be understood. As George Jochnowitz who wrote the review kindly explains, Robert Brasillach and those who think as he did “have amputated parts of their brains.”

Editor’s Note: This essay is featured in Jared Taylor’s book, If We Do Nothing, available for purchase here.