Reconsidering Slavery

Chris Woltermann, American Renaissance, November 2009

Gary Lee Roper, Antebellum Slavery: An Orthodox Christian View, Xlibris, 2009, 329 pp.

Something about the contemporary American South puzzles me: How can Southerners, whose liberal attitudes about race and historical interpretation put them comfortably in the national mainstream, condemn their ancestors’ practice of African slavery while still revering their region’s antebellum culture and the heroism of the men and women who defended it during the Civil War? The short answer is that the New Southerners — and there seem to remain few Southerners of the unreformed kind — cannot sustain this balancing act, just as no decent person can admire the ingenuity and panache with which a pedophile seduces his victims. Even the ostensible nobility of Robert E. Lee or Stonewall Jackson becomes venal and ugly when seen as a buttress to the allegedly absolute evil that was slavery.

I believe the future of Southerners as a self-identified people requires them to come to terms with their slavery-based past in some way other than by repudiating it. They must, in other words, undertake a moral rehabilitation of historical Southern slavery. To this end, Rev. Gary Lee Roper has written Antebellum Slavery: An Orthodox Christian View. As he explains:

“The partisans who write books praising the virtues of the South and our glorious heroes more often than not fall all over themselves apologizing for slavery. I repeat, if our ancestors — who were citizens of the antebellum South, slaveholders or nonslaveholders — necessitated us, their descendants, to make copious apologies for a culture they all tolerated, those ancestors deserve only our contempt not our adulation.” (Italics in original.)

Rev. Roper offers us history of the best kind. This book is about the past, informed by a present-day perspective, and meant to further the author’s aspirations for the future. Rev. Roper sees a lethal threat to Southerners in their widely felt need to apologize for slavery. In his view, apologies themselves are immoral acts; they voice regrets for an institution that was not evil in his view and therefore does not now require retrospective penitence.

Rev. Roper argues from the Bible that slavery is not morally objectionable. He writes that like all legitimate institutions, including the family and government, it is subject to abuse, but it is not on that account inherently depraved. Although secular critics will disagree, Rev. Roper writes that slavery came into being because of man’s fallen nature and is a condition that results from Original Sin.

Most Christians today reject Rev. Roper’s Christian defense of slavery. Hilaire Belloc was among those who argued that the whole tenor of Christianity goes against affording slavery the slightest moral status. This is ahistorical nonsense. Rev. Roper conclusively shows that both the Old and New Testaments accepted slavery without qualifications. Particularly instructive is St. Paul’s admonition to a runaway slave, Onesimus, to return to his Christian owner.

The history of the Church confirms Rev. Roper’s inferences drawn from the Bible. Neither the early Church Fathers nor the Church Councils nor hardly any Christian authorities until about 1800 denounced slavery as an immoral institution. Rev. Roper refutes the view that early Christians merely tolerated Roman slavery in order to avoid persecution. Christians were prepared to face a martyr’s death by refusing to honor heathen idols. If slavery were the moral absolute that modern Christians claim it is, the early Christians could have condemned it as readily as they did pagan worship. They did not.

Readers determined to be unreceptive to Rev. Roper’s book accept the conventional view that Southern slavery was uniquely wrong because, as a racially based system of chattel slavery, it perpetrated worse outrages than did other kinds of forced servitude. Rev. Roper debunks this myth with much evidence and cogent argument.

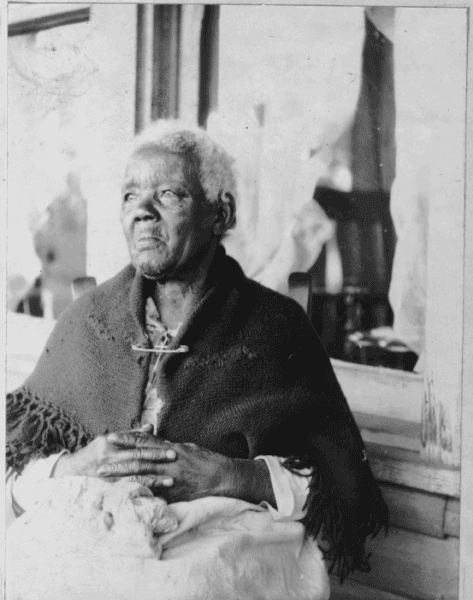

First, there is the testimony of the former slaves themselves. From 1936 to 1938, more than 2,300 were interviewed as part of the Depression Era’s Federal Writers’ Project. Much to the consternation of the government’s liberal interviewers, 86 percent of comments about former slave masters were positive. Many facts render these comments credible.

Former slave Sarah Gudger at the age of 121 circa 1937. (Credit Image: Library of Congress / Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project)

Black families were not often separated. Children were sometimes sold away from parents, and spouses were occasionally separated, but comprehensive sales records from 1804 to 1862 for the city of New Orleans, the largest market in the South’s inter-regional trade, show that this was very unusual. Rev. Roper notes that white families in the North also suffered involuntary breakups because of financial panics and factory layoffs.

Contrary to myth, family life in most slave households was patriarchal, strong, and stable — exactly as the owners wanted. Sexual morality was strict, even among unmarried adults. To the extent that valid comparisons are possible, Rev. Roper shows that domestic violence in slave households was probably less than among blacks today. The illegitimacy rate was certainly much lower.

Were slaves not routinely beaten, poorly fed, and treated badly? No. Beatings only made slaves sullen and hostile. Rev. Roper explains that good treatment and incentives, including cash, worked better. Some planters even shared profits with their slaves. Nor were work demands nearly as onerous as Hollywood suggests. On most plantations, very little work was done in August because of the crop cycle and the summer heat. August became a time of relative relaxation, with barn dances, church meetings, opportunities for courtship, etc.

The slave diet was generally nutritious. A typical slave received about six ounces of meat daily. According to several modern scholars whom Rev. Roper cites, the slave diet exceeded today’s government dietary standards.

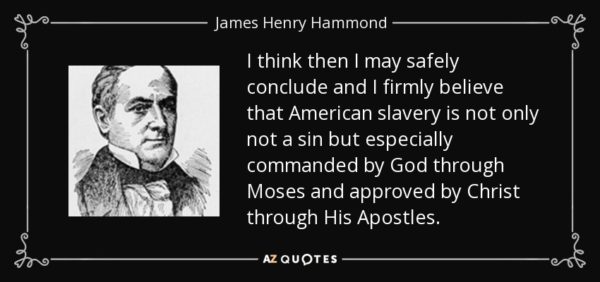

Rev. Roper convincingly argues that Southern slavery was not even remotely akin to the “work-them-to-death” pattern of slavery in other contexts, such as the mines of classical antiquity, the North-African galleys and farms, or the plantations of French-ruled Haiti. Slavery in the old South was not an easy life, but neither was that of Northern workers. In 1858, Senator James Henry Hammond of South Carolina replied to a Northern attack on Southern slavery by arguing that so-called free workers were really no different from slaves. “The sole difference,” he said, “is that our slaves are hired for life and well compensated. . . . Yours are hired by the day, not cared for, and most scantily compensated.”

Some Northern workers agreed. In 1834, one bitter white worker expressed his resentment of upper-class white women in verse:

Their tender hearts were sighing

As the negro’s wrongs were told

While the white slave was dying

Who gained their father’s gold.

Northerners made moral arguments for abolition but capitalists had other reasons for it. Many thought slaves had too much leisure, and believed more work could be wrung out of them as free laborers than as slaves.

Rev. Roper argues that Southern slavery not only avoided being superlatively awful, it was advantageous to blacks. Here his case is such an assault on mainstream thinking that some readers will have to make an effort to remain open-minded. Rev. Roper writes that slavery’s main benefit was to bring slaves to Christianity. He also notes that slavery in Africa was widespread, of longer standing, and could be far more cruel than American slavery. For example, on the death of Freempoony, king of the West African Akim tribe, his followers reportedly broke the bones of several thousand of his slaves and buried them alive. (Rev. Roper cites a 19th century source but does not say when this incident occurred.)

The contemporary benefit, Rev. Roper asserts, is the quality of life enjoyed by today’s descendants of slaves. Rev. Roper was witness to starving children during travels with a missionary in Africa, and readers are no doubt aware of atrocities committed in Darfur and of the recently ended civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Is it so outrageous to think that the American progeny of slavery are better off than if they had been born in Africa?

Rev. Roper’s defense of Southern slavery does not mean he regrets its end. He rejoices in the freedom of blacks, but he writes bitterly about the horrific way in which Divine Providence effected their freedom. His orthodox Christian readers might prefer he were more humble and, if one dare say so, Augustinian in his acceptance of the fruits of Lincoln’s War. St Augustine noted that God often works his will inscrutably through Christian peoples, and surely this includes those on both sides of the slavery divide.

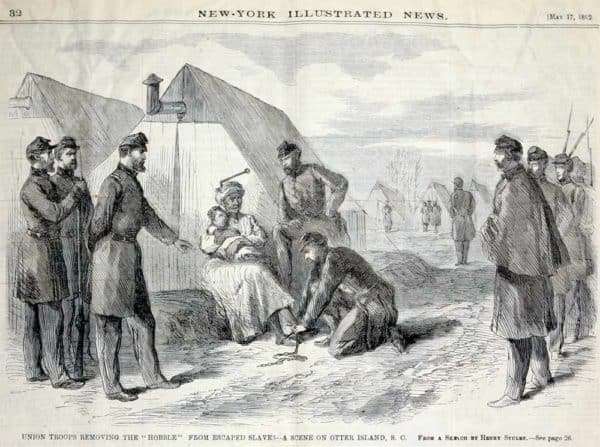

From New York Illustrated News, May 17, 1862. The caption reads, “Union troops removing the ‘hobble’ from escaped slaves — a scene on Otter Island, S.C.”

To be fair, Rev. Roper does sometimes take this view, as when he writes that “God has opened our knowledge to machinery and technology,” thus making slavery obsolete. Machines have replaced animals as well as slaves. An Augustinian would say that God’s influence can be inferred from the scientific and industrial revolutions that arose, not coincidentally, in the Christian West.

Nonreligious readers, among whom I count myself, would appreciate an expansion of Rev. Roper’s arguments beyond his Biblical approach. He could have cited the work on racial differences of such authorities as Arthur Jensen, Richard Lynn, Philippe Rushton, and Michael Levin. These race realists argue that innate, genetically rooted differences in intelligence and individual character help explain both interracial relations and cultural/behavioral differences between races. This perspective supports many of Rev. Roper’s observations about how Southern antebellum slavery actually worked.

Rev. Roper may have chosen not to include this perspective because he clearly disdains naturalistic interpretations of human affairs. He may also feel that race realism threatens to undermine the Christian promise of universal brotherhood in Christ. Finally, Rev. Roper may fear — perhaps not correctly — that the conclusions of the race realists would offend blacks, a people for whom he bears no ill will and, instead, seems to have a high regard.

Unfortunately, the excellent content of Antebellum Slavery is not always well edited. There is repetition and too many errors in grammar and punctuation. Numerous digressions also detract from the book. A two-page diatribe against Horace Mann’s educational philosophy adds nothing to a discussion of the abolitionists. Similarly, an account of deplorable conditions in modern Haiti is not relevant to Southern slavery, although Rev. Roper could have put this in the wider context of race realism.

Readers will be well rewarded, however, if they focus on the essential arguments of Antebellum Slavery. This fearless and unequivocal defense of the Old South will be useful for all who seek to understand the fallacy of apologizing for slavery, and Rev. Roper has taken an important step toward restoring the self-respect not only of Southern whites but all Americans. Rightly understood, Antebellum Slavery fosters legitimate pride in blacks as well as whites; unwarranted, morally flawed apologies benefit no one.