Fruits of an Unfettered Mind

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, March 2004

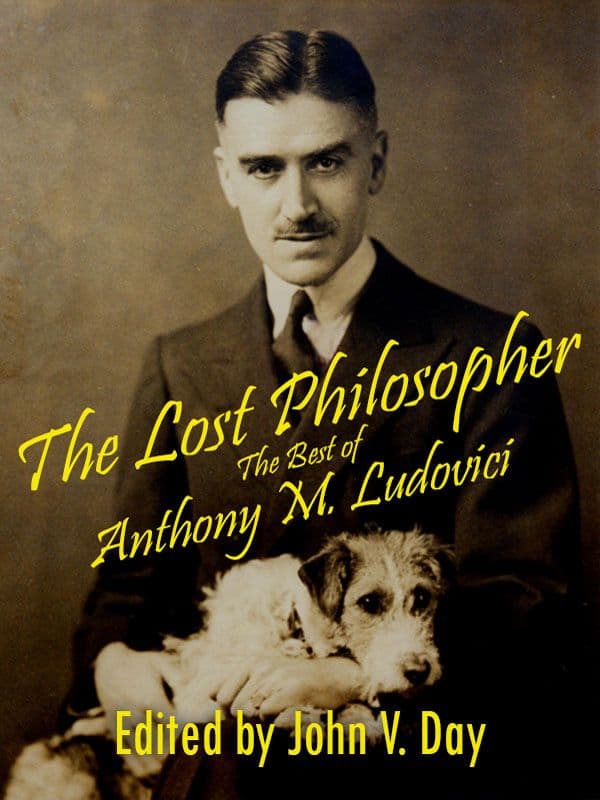

John V. Day, Editor, The Lost Philosopher: The Best of Anthony Ludovici, Educational Translation and Scholarship Foundation, 2003, 305 pp.

Is racial consciousness always part of a conservative view of the world, or is it compatible with what is known as liberalism? At the present time, when consciousness of race is rare among whites, it is usually associated with conservative thinking. Some have pointed out, however, that this was not always so: that for centuries, racial consciousness was part of the common heritage of whites, uniting men who were otherwise antagonists.

The now-forgotten British author Anthony Ludovici (1882–1971), reintroduced in this new collection edited by John Day, would have argued that racial awareness is inherently conservative. He was a novelist, critic, and essayist who, in the 1920s and ‘30s, was one of Britain’s most prominent writers. This is a volume of selections from his many books, and includes passages from A Defense of Aristocracy, Woman: A Vindication, The Night-Hoers, The Choice of a Mate, Religion for Infidels, A Defense of Conservatism, and Man: An Indictment.

Ludovici wrote on a variety of subjects, but some of his favorites were conservatism, eugenics, women, aristocracy, and religion. He was frankly elitist in a way that would get him drummed out of polite society today, and in his own time never trimmed his opinions to advance his career. He did not write mainly or even at particular length about race; he simply took it for granted in an age in which it was common to do so. A conviction of the importance of race, heredity, and national character colored his approach to all questions. His views, therefore, are one indication of the turn of mind a thoughtful man fully conscious of race may take.

Ludovici thought deeply about what a nation required in order to prosper, what sort of men should lead it, and how they should approach their work. He was convinced there could not be progress or happiness without stability. “Conservatism,” he wrote, “is of enormous value, because it is only in a stable environment that the slow work of heredity can build up family qualities, group virtues, national character and racial characteristics.”

In his view, the goal of a politician should be to increase his nation’s prestige, power, and health, but also to “preserve the identity of his nation throughout change,” and to “preserve the national character.” Preservation meant a deep skepticism of faddish uplift programs, and sudden innovations of all kinds. Of the responsible politician, he wrote:

[H]e knows enough about the character and potentialities of his people, and about the eternal characteristics of healthy mankind in general to be able to judge whether new tendencies are possible or fantastic (i.e., whether they are in keeping with the eternal nature of men, or the particular character of his nation, or whether they apply only to angels, goblins, fairies or other romantic fictions, who alone seem to suit the exigencies of hundreds of modern hare-brained schemes).

Ludovici emphasized “the eternal nature of men” because misreadings of human nature lead to disaster:

[A]bove all, the true conservative entertains no high-falutin’ notions about the alleged radical goodness of human nature. All his political schemes, whether they deal with home or foreign relations, are always therefore conceived on the assumption that guile, egotism, acquisitiveness, venality, lust of power, abuse of power and duplicity are likely to be manifested by the groups of humanity concerned, and consequently he is not prone to imagine utopias or ideal states . . .

Politicians must respect both “eternal human nature” and distinctive national character. Ideas and institutions that suit some countries do not suit all. This is, of course, completely at odds with the modern view (fortunately now under attack) that behavior can be infinitely molded and that “democracy” and “women’s rights,” and MTV are the happy ending for all mankind.

So concerned was Ludovici about maintaining national character, that he believed only deep-dyed Englishmen should ever make laws for the English. The thoughtful man, he wrote:

. . . believes in the advisability of having as politicians not only men who can lay some valid claim to a knowledge of humanity, but also men who belong to the stock of those whose policy they are called upon to direct. He also disbelieves, therefore, in having Jews or men of foreign extraction or odd people — that is to say, eccentrics, cranks and fanatics — as politicians in an English Parliament.

Ludovici promoted homogeneity: “Because he believes in character, health, good taste and pure stock, the conservative must always be opposed to miscegenation and the flooding of his country with foreigners.”

Liberals, by contrast, are always trying new, silly schemes that harm the country. Liberalism, he wrote aphoristically, is “the uncritical misunderstanding of all change as progress.” He also was convinced that “it is part of the superstition and short-sightedness of liberalism to suppose that a continual stream of new laws and an incessant remodeling or demolition of institutions can restore a nation’s health and happiness.” This describes very well the American political fashion for “new ideas” and “social programs,” as if it were impossible for a country to get its laws and institutions right and then leave them alone. As Ludovici explains, “only a handful in every generation can bring about change which is elevating.” Most change is degeneration.

This frenzy for change, explained Ludovici, comes from democracy: “Give the millions freedom to influence the nation’s destiny and you must expect individuals to see advantage in a change which is advantageous only to themselves and their like. Their private interests will take precedence of national interests.”

Most of this narrow agitating takes the form of appeals to equality, a concept Ludovici found repulsive and dangerous: “It must . . . be the undesirable, the unskillful, the incompetent, the ugly, the ungifted, in all walks of life, the incapable of all classes, who want equality,” because the wealthy and talented can be brought down and persecuted but ordinary men cannot be made extraordinary. The more heterogeneous a society, the more differences in ability and achievement there will be, and the less favored will have even more reasons to agitate for leveling.

Putting decision-making power in the hands of the people at large must fail because “it is notorious that everywhere on earth the wise, intelligent and discriminating members of the community always constitute the minority.” The ballot is therefore a disastrous way to choose leaders:

“The person selected by mediocrities to represent them must therefore be a man capable of appealing to such people — that is to say, a creature entirely devoid of genius either for ruling or for any other function. As a matter of fact, all he need possess is a third-rate actor’s gift for haranguing his electors about matters they can easily grasp, in language calculated to stimulate their emotions, and he must be guaranteed to hold or to express no original or exceptionally intelligent views.”

Ludovici believed aristocracy was the best form of government: “Aristocracy means essentially power of the best — power of the best for good, because the true aristocrat can achieve permanence for his order and his inferiors only by being a power for good.” He added, however, that it was fatal for aristocracies to be closed or strictly hereditary, and that enlightened aristocrats must always be looking “for men of honor, taste and proper ideas and draw them into the aristocracy.”

Ludovici was not optimistic that aristocracy could be restored: “[T]he people of these [Teutonic and Anglo-Saxon] races will require to see their civilization in ruins about them, as a result of their experiment with democracy, before they will be prepared to alter their opinion of the subject of democratic institutions and agree to label them ‘Poison’ for all time.”

Women

John Day, who edited this collection, writes that differences between the sexes were one of Ludovici’s favorite subjects, and The Lost Philosopher contains long passages about women. Like virtually all men who recognize individual and racial differences, Ludovici believed men and women have different roles, but warned that the highest calling of women did not get nearly enough recognition: “[T]he housewife among the poor who rears a family and discharges all her household duties as well is a heroine,” although in a society that increasingly admired only money, “it was inevitable that unremunerated duties, like those of domesticity and motherhood, should be bereft of dignity.”

Ludovici thought that the care and devotion of a mother were essential to setting a man on the course of greatness: “Anything else that . . . [a woman] may do must be always second best to this, and those who, by misrepresentation and appeals to vanity, persuade her while she is yet quite young that there are callings better than, or at least as good as, motherhood for her are enemies not only of woman, but also of the species.”

A certain amount of patronizing is to be expected from conservatives of previous generations, but Ludovici tends to take an insight about sex differences and exaggerate it to the point of misogyny. He believed, for example, that women naturally pity and look after the weak because an inclination to care for the helpless is a requirement for those who deal with babies, and that this leads to an “attitude of irrational tenderness to cripples and the physiologically botched.” He thought many women were liberals because of what people now call their “nurturing” nature — something that is probably true — but went rather far when he concluded that “this blind instinct necessarily involves a deep-seated and incorrigible lack of taste.” Women, in other words, cannot tell a permanent leech from someone who will improve with help and care. Ludovici also wrote of the female “love of petty power,” which feasts on the helplessness of infants and makes mothers prefer babies to grown-up children.

Ludovici thought that for a woman, emotions are so strong they commonly interfere with rational thought:

Her convictions are so intimately and unconsciously interwoven with her deepest interests and long-cherished beliefs that if, to accept a certain truth, these convictions have to be outraged, she prefers to reject that truth as unacceptable. In this sense, woman’s thinking is largely feeling and her thoughts are largely sensations. The more emphatic and stubborn a woman is in any belief, the more strongly you may suspect that she has not facts but emotional reasons for holding it. That is why women are so notoriously bad at giving reasons for their opinions . . .

Women, Ludovici believed, were not fit for positions of power because a woman does not value men for ability or character but for how they treat her. “This is a comparatively harmless trait,” he wrote, “so long as woman has no power; the moment, however, that she is placed in a position of wielding power, her errors of judgment affect public life, and she only accepts those men as her ministers, advisers or directors who can prostrate themselves with the best grace at her feet, and appeal most irresistibly to her vanity.”

Ludovici also wrote that women see other women as competitors and have a natural loathing and contempt for them. He advises men that if they want to cure a defect in a wife or daughter, they need only point out the same defect in some other woman whom she knows and dislikes.

Ludovici thought women evaluate potential husbands far too narrowly:

Woman, like the female butterfly, the female housefly or the female horsefly, has the very vital and useful instinct to deposit her eggs only where there is a sound promise of food, and ample quantities of it . . . It is not the best-looking repository, or the most refined, or the most learned, or the most artistic, that is sought, but the repository which promises the richest food-supply for the coming brood.

“[T]he man who kills most female hearts,” he added, “is he who can throw a rich fur around his capture and whirl her off in a sumptuous Rolls-Royce. This to the normal decent woman is simply irresistible.”

The habit of evaluating men by their income is life-long: “Thus wives who have passionately loved their husbands will learn to dislike and despise them intensely if owing to some unhappy turn in their fortunes they become material failures. Daughters will also manifest a pronounced dislike towards fathers who, for their station in life, have been inadequate material successes.”

Ludovici wrote that this female preoccupation with materialism spreads to the whole society as women gain power: “It is indeed one of the most pernicious results of woman’s ascendancy in any society that this vulgar pursuit of mere material success (because it provides the surest provision for the offspring) tends to become general . . .” He complains elsewhere of “the stampede for wealth and success in modern, women-ridden society.”

Not surprisingly, Ludovici believed all women should, at all ages, be under the guidance of a man.

Eugenics

Like many men of his time, Ludovici understood that traits are hereditary, and he wrote very forcefully about the folly of welfare: “Every sixpence paid by a desirable couple in taxation and rates for the upkeep of human rubbish is a sacrifice of the greater to the less, and if such a desirable couple curtail their family to meet national expenditure for degenerates, we plainly kill the best to save the worst.” He would not only have encouraged the best to reproduce but wrote that “we must boldly rid ourselves of the feminine and morbid sentimentality” that keeps us from “purging our society of its human foulness.”

He was bitterly opposed to contraception because only superior people who think ahead will use it, and will thus deprive the nation of superior children. “[T]he sale or handling on of contraceptives to desirable and sound couples might be as severely punished as at the present day we punish attempts at poisoning,” he wrote, and urged that “contraceptives . . . be sold as some poisons are now, only on a doctor’s prescription.”

“Marriage between all defectives and degenerates should be forbidden by law,” he argued, and “all acute cases of malformation, degenerative stigmata, crippledom, abnormality should be unhesitatingly done away with . . .” He could not understand people who insist on a dog with a pedigree but do not care about human pedigrees. He thought it only natural to seek to marry someone very like oneself, and “from the mating standpoint,” he wrote, the attitude of an Englishman or -woman should be: “You may be sound and all right as a Negro or a Chinaman, but to me you are repulsive and therefore to be rejected.”

Like so many advocates of eugenics, Ludovici had no children, but on his death in 1971, he left “70,000 pounds to the University of Edinburgh for the study of the effects of miscegenation, especially between blacks and whites. The university declined the bequest.

Out of Step

There was one respect in which Ludovici was out of step with what we generally consider conservatism today: He was passionately anti-Christian. He thought the New Testament’s interest in tavern-keepers, prostitutes, the weak, and the sick was implicit encouragement for dysgenics. He also disliked the universal nature of Christianity, and admired the ethnic exclusiveness of Judaism.

Ludovici also found some of the commandments unrealistic: “No command can make one love anyone who is not lovable. ‘Seek neighbours that are lovable so that you may inevitably love them’ would have been more sensible. ‘Love one another’ is shallow and reveals a poor, almost benighted grasp of human psychology.”

He also thought Christianity, as it was practiced by Europeans, was a cold-weather religion. “The sun is pagan,” he wrote:

In short, it urges man and woman to a wanton enjoyment of life and their fellows; it recalls to them their relationship to the beasts of the field and the birds in the trees: it fills them with a careless thirst and hunger for the chief pastimes of these animals — feeding, drinking and procreation; and the more ‘exalted’ practices of self-abnegation, self-sacrifice and the mortification of the flesh are easily forgotten in such a mood.

Ludovici could not accept Christianity but he recognized the stabilizing role of religion. He thought religion was good for people, but that Christianity was a bad choice.

Ludovici’s view of Christianity may have been influenced by Nietzsche, whom he admired. He agreed with Nietzsche in his conviction that men naturally seek power and dominance, writing of “those numbskulls who begin to see and think of the will to power only when figures like Napoleon, Stalin, or Hitler appear, and who overlook it wholly in themselves, their wives, their children, and their cat . . .”

He believed this meant there could never be utopia — conflict is written into human nature: “What possible trace of realism remains in Shaw’s attribution of all wickedness to poverty, or in Marx’s implication that what men call ‘evil’ will disappear when once a classless society is established?”

Ludovici also took a Nietzschean view of the relationship between character and free will:

To the strong there is no such thing as free will, for free will implies an alternative and the strong man has no alternative. His ruling instinct leaves him no alternative, allows him no hesitation or vacillation. Strength of will is the absence of free will . . .

To the strong there is also no such thing as determinism as the determinists understand it. Environment and circumambient conditions determine nothing in the man of strong will. To him the only thing that counts, the only thing he hears, is his inner voice, the voice of his ruling instinct.

Only the weak, who do not have a consistent internal voice, appear to be free because they can act without consistency.

The editor of this collection calls it The Lost Philosopher, but the selections he offers do not justify the title. Ludovici was more an essayist than a philosopher, even if he did develop some of his subjects in detail. What today’s readers are most likely to hold against him, however, is his habit of asserting something — something that may even be true — without any substantiation. He simply asserts, for example, that women are emotional and, consequently, unfit for public office. This is fine for people who already agree with him, but not much use for anyone else.

At the same time, though, there is charm in Ludovici’s straightforwardness, his unwillingness to qualify or explain. Today, anyone who strays the least bit beyond the liberal pale must spend half his book clearing his throat, shuffling his feet, and apologizing for hurt feelings. It was a sign of the good health of the decades in which Ludovici was active that he could write as he did — and no doubt shock a few people in the process — and yet retain a wide readership and high professional standing.

“Biologically, absolute beauty exists only within the confines of a particular race,” he once wrote, adding that anyone who begins to think people of other races are beautiful has begun to cut himself off from his own race. Ludovici offered no data to support this view, cited no authorities, provided no further explanation, and did not apologize to anyone whose feelings he might hurt. We must envy both the man who wrote this and the age in which he wrote it for freedoms that have now all but disappeared.