By 2084, Will Islam Rule the World?

Brian Martin, Spectator, March 2017

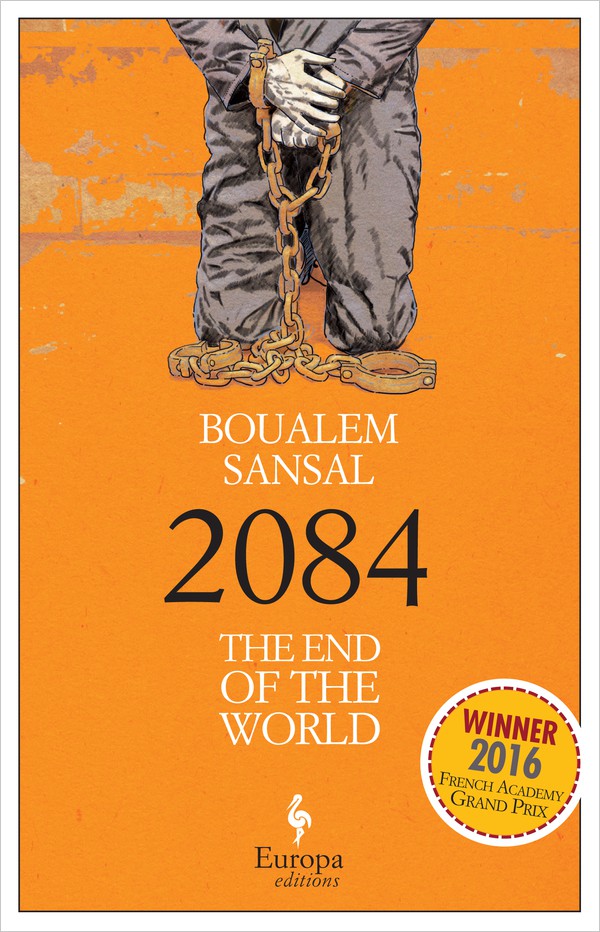

2084: The End of the World by Boualem Sansal, translated from the French by Alison Anderson, Europa Editions, pp.240, £11.99

Boualem Sansal’s prophetic novel very clearly derives its lineage from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. A totalitarian surveillance state, a fundamentalist religious autocracy, is portrayed as being totally intolerant of free-thinkers. This is a powerful satire on an Islamist dictatorship. It is unsurprising that Sansal’s writings are censored in his native Algeria.

The religious structure of the political state is familiar. The one true god is Yolah and his prophet or ‘Delegate’ is Abi. Abi’s book, the Gkabul, is the foundation of the religion; it is sacrosanct and immutable. Places of worship are mockbas and the nation is named Abistan after the true disciple. There are nine calls to prayer each day. An official language has been instituted, Abilang. Orwell’s Newspeak chimes in the memory.

The state’s hierarchy mimics regimes we recognise. Abistan has its supreme leader, its Just Brotherhood, its Apparatus, ministries that oversee every aspect of society; they all watch over a cowed and depressed population. Anyone who is detected dissenting from established views, by official investigation or by the evidence of informers, is arrested and taken for public execution by stoning or beheading to one of many stadiums. Women are hardly noticeable and rarely mentioned; their masks and burniqabs render them ‘fleeting shadows’.

Sansal’s target is obvious — the desired universal caliphate of Islamist extremists, the so-called Islamic State. The narrative tells us of Ati, a young man who suffered from tuberculosis. He recovered at an isolated sanatorium in the mountains where people were mostly neglected and died, or survived merely by chance. Ati makes a long, difficult caravan journey back to Quodsabad, the capital; his experience and chance acquaintances lead him to doubt the authenticity of the religious state.

His quest for personal liberation and freedom of thought is the story. Sometimes, like Ati himself, we might tend to get lost in its labyrinthine complexity, but as with Ati, perseverance is rewarded. Like Peking, Qodsabad has its interior forbidden city, the City of God; and like China or the USSR, Abistan has its corrupt nomenklatura. As with Stalin’s Red Army, soldiers who have come into contact with ‘abroad’, when returned home, are exterminated. Abistan even has its civilian ‘disappeared’.

Sansal spares us nothing of the horrors of the autocratic state, its hypocrisy, its deceptions and malicious contrivances.

Michel Houellebecq’s subtle, threatening, frightening novel Submission imagines the democratic takeover of France by Islamist politicians. 2084 follows on, and has terrifying implications for the entire world.