Black Insurrection

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, August 2000

Denmark Vesey, David Robertson, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999, 202 pp.

Denmark Vesey was the leader of what was by far the most complex and elaborate attempt to mount a slave insurrection in the United States. The plot failed when loyal blacks informed the white authorities, but by then some 9,000 slaves had agreed to rise up on July 14, 1822, kill every white in Charleston, South Carolina, and escape by ship to Haiti. Novelist and biographer David Robertson has written an absorbing account of the Vesey plot but spoils it with racial moralizing.

Mr. Robertson reports that we have only bare-bones accounts of Denmark Vesey’s early life. He was probably born in the early 1760s, either in Africa or the Virgin Islands. He took his name from Captain Joseph Vesey, a slave trader who first sold him in Haiti as a cane field worker. Vesey did not care for field work and he faked epileptic attacks to convince his master he was an invalid. Captain Vesey obligingly took back the “defective” merchandise, refunded the sales price, and put Denmark to work as an assistant in the slave trade. He must have realized that his slave had faked his disability, but he had singled him out early for his “beauty, alertness, and intelligence,” and by all accounts treated him kindly for the 19 years he owned him.

Capt. Vesey lived in Charleston when not at sea, and in 1800 Denmark bought the winning ticket in the city lottery. Richer by $1,500, he bought freedom for $600 and established himself as a carpenter. For 22 years he lived as a free man, eventually joining the prestigious Second Presbyterian Church and living in a comfortable house only three blocks from that of the governor, Thomas Bennett. He was prosperous, and well liked by blacks and whites.

Free blacks were not uncommon in Charleston. In 1800, blacks outnumbered whites 63,615 to 18,768 but 1,475 blacks — or 2.3 percent — were free. Many were mulattos and some were prominent citizens. The finest hotel in town was owned by a free person of color, Jehu Jones, and Governor Bennett favored him with the official patronage of the administration.

Vesey did not invite men like Jones into his plot, fearing they would side with the whites. He did not approach a single free black, and seems to have been deeply suspicious of mulattos. It was only slaves he wanted for his insurrection, and he spent several years and traveled as far as 60 miles to recruit them. Although he mixed with whites at the Second Presbyterian Church, he found that the African Methodist Episcopal Church was an effective network for rebellion, and many of his close confederates were AME members.

Vesey worked out his plans with great care. He chose the night of July 14, for example, for several reasons. First, many whites, including a large number of military officers, fled the heat of Charleston in the summer to vacation in the north. Second, July 14 was to be a moonless night, and finally, it was the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille.

Vesey organized his attack so that slaves, who had been steadily caching stolen weapons, were to form armed columns and converge on Charleston from the north, south, and west. They were to take the federal arsenal, loot weapons shops, and murder every white they could find. All conspirators with access to horses were to ride through the streets attacking whites. Trusted house servants of the governor, mayor, and other men in authority were to murder their masters as they slept. The only whites to be spared were ship captains who would sail them to Haiti, and a few women they would bring along for purposes Mr. Robertson does not specify.

Vesey told his followers — probably falsely — that he was in contact with the government of Haiti, which would send an army to back the uprising. He also claimed he had arranged for a refuge somewhere in Haiti. Although this was probably not true either, he planned to rob all the banks before burning Charleston to the ground, so the ex-slaves might have bought themselves a welcome somewhere in the Caribbean. Some of Vesey’s plans were fanciful. A few blacks were to disguise themselves as whites by painting their faces and wearing wigs and beards made from the hair of whites. This was to allow them to approach close enough to whites to kill them.

A leak derailed the plot. On May 25, a conspirator named William Paul approached another slave with word of the rebellion. That slave was loyal to his master and quickly told the authorities, who arrested Paul on May 31. Under interrogation, Paul described the extent and participants of the plot, but whites refused to believe him. That the governor’s trusted slave, Ned Bennett, had agreed to murder his master in his sleep, that thousands of slaves from the surrounding area planned to exterminate the whites of Charleston — this was too preposterous to be believed.

And yet, evidence continued to mount, and whites arrested more ringleaders. Despite the many fingers pointing at Vesey, he remained at liberty for several more weeks — until June 22 — because the authorities could not believe a prosperous, well-behaved free black would lead an insurrection. In the meantime, as his henchmen were rounded up, Vesey tried to advance the date of the attack to June 16. Word of this, too, got out but Vesey, though still free, was unable to rouse his people to the attack. Whites passed a sleepless but uneventful night standing guard over the city. By the time Vesey was finally arrested even the black womenfolk were wondering openly why he was still at liberty.

The conspirators got formal but quick trials at the Work House where they were held, with masters often acting as defense counsel for their slaves. Most whites seem to have thought their blacks incapable of disloyalty, and Mr. Robertson enjoys describing the loss of their illusions. In this account of the arrest of John Horry, he includes passages from a contemporary source:

‘[W]hen the constables came into Mr. Horry’s yard to take up his waiting man,’ the slave’s master, Elias Horry, insisted ‘they were mistaken, that he could answer for [John’s] innocence, that he would as soon suspect himself.’ Elias Horry attended his slave’s later trial at the Work House, and, upon hearing the state’s evidence, plaintively asked his waiting man: ‘Tell me, are you guilty? For I cannot believe unless I hear you say so . . . What were your intentions?’ To which John Horry . . . answered, ‘To kill you, rip open your belly, and throw your guts in your face.’

It clearly pleases Mr. Robertson that whites trusted and even loved blacks who hated them.

In all, the authorities arrested 131 conspirators and executed 35. Vesey was hanged on July 2 despite fears there would be a slave uprising to save him. The city tried to conduct the executions without fanfare but there were reportedly large crowds of both whites and blacks to witness the hanging. If he spoke any final words they were not recorded.

Vesey himself remains a mystery. Mr. Robertson seems to take it for granted that any free black would want to lead slaves in exterminating their masters, but this was obviously not the case. Vesey himself did not trust free blacks and apparently thought only slaves would be willing to fight. He, himself, led a comfortable life and could have emigrated to Haiti any time he wanted. It must have taken an unusual degree of racial solidarity to risk death in an undertaking in which he had so little to gain, but nothing is known about the man’s psychology and Mr. Robertson does not speculate.

It must also have taken unusual ability to organize a network of no fewer than 9,000 men (feminists are no doubt grieved that Vesey invited no women to take part). Vesey and his lieutenants threatened to kill traitors but it is still a wonder the uprising stayed secret as long as it did. If thousands of slaves really had mounted a surprise, dead-of-night attack on the city, there is no telling how much murder would have ensued.

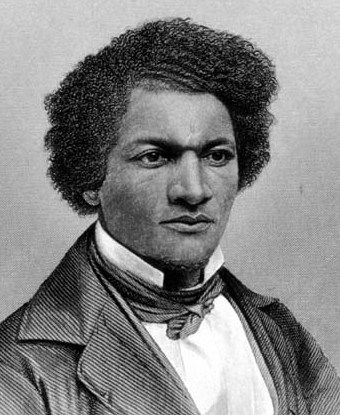

Of course, it is now fashionable to think of Denmark Vesey as a noble freedom fighter. In 1976 the city of Charleston honored him by hanging an imagined portrait of Vesey in the municipal auditorium.

Mr. Robertson himself adopts a condescending attitude towards 19th century whites that is as silly as sneering at them because they didn’t have electricity or automobiles. Irritating 20th-century moralizing crops up whenever the motives of whites are not known; Mr. Robertson assumes they were low. Blacks, on the other hand, do no wrong, except to betray Vesey, whom Mr. Robertson calls “an attempted great liberator.”

Mr. Robertson’s prejudices lead him into contradictions. He marvels at the extent and complexity of the Vesey plot but thinks the hangings were harsh and excessive. With no apparent sense of irony, he asks us to admire a plan to exterminate the whites of Charleston but to condemn the execution of 35 ringleaders. He repeatedly suggests the trials were unfair, yet leaves no doubt that those found guilty were determined to commit murder, arson, and robbery on a grand scale.The current hysteria about race may make this sort of thing inevitable, but moralistic preening is not the same as writing history.