The Racial History of Gary, Indiana, and the Need for Restrictive Covenants

Paul Kersey, SPBDL, September 13, 2012

It’s a city time forgot; it’s a history lesson that we purposefully skip over; it’s yet another reminder that “Manifest Destruction” (the Great Migration of Blacks from South) was the most devastating event in American history.

Gary, Indiana.

In S. Paul O’Hara’s Gary, the Most American of All American Cities we are introduced to a city whose collapse mirrors that of Detroit (described in vivid detail in Escape from Detroit:The Collapse of America’s Black Metropolis

): with a population that nearly 100 percent white in 1920, Gary saw a migration of 15,000 Black migrants between 1920 and 1930. At 18 percent of the population of Gary in 1930, another 20,000 Black people would join them by 1940–lured by work in the steel mills.

Through high fecundity rates (maintaining close racial solidarity), the percentage of Blacks would slowly begin to overwhelm the white population; by 1967, Black people would be able to elect Richard Gordon Hatcher as one of the first Black mayors of a major city in the nation.

Time magazine would report the election of Hatcher was a victory, not because of race, but due to a desire to reform the political process. Nevertheless, the magazine would report:

“Shouting, dancing Negroes weaved wildly through the six downtown blocks of Gary, Indiana.”

Today, Gary, Indiana is 84 percent Black. USA Today called it a “ghost-town” in a 2011 article [Gary, Ind., struggles with population loss, by Judy Keen, 5-19-2011]:

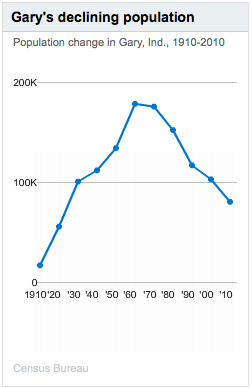

The 2010 Census crystallized Gary’s decline: The population, which peaked at 178,320 in 1960, is now 80,294. From 2000 through last year’s count, Gary lost 22% of its residents. The city’s unemployment rate in February was 9.8%.

Gary — like Detroit, which lost 25% of its people in the past decade — faces tough questions: What is the best way to shrink a city? How can city government provide adequate services as its tax base contracts? How can new employers and residents be wooed to a place known more for blight than for opportunity?

The city has cut many services and decided last month to close its main library, which opened in 1964. A state board raised property tax caps this month and set Gary’s tax levy at $40.8 million. If the caps had not been increased, Gary would have been allowed to collect only $30 million. It was the third and final time the city can seek such relief.

A plague of vacancies

Gary was founded in 1906 by U.S. Steel, which still employs 4,727 here. Last year, the company announced a $220 million modernization of the Gary plant.The city’s decline began in the 1960s as overseas steel production squeezed U.S. makers and accelerated in the 1970s as “white flight” prompted the rapid growth of surrounding cities. More than 80% of Gary’s residents are black.

Wait a second: why can’t the 84 percent Black population sustain the wealth that white people left behind? Why can’t they keep alive the businesses? Why can’t they keep alive the high property valuations? How come the migration of Black people to Gary brought high levels of crime and violence that caused white people to flee the city? Why can’t the majority Black population ignite that entrepreneurial spirit, innovate, attract outside investments, and diversify the economy (as happened in Pittsburgh — another city built on steel)?

The answer is self-explanatory: because the population is less than 10 percent white and 84 percent Black.

Because Black people (outside of state and federal welfare, handouts, subsidies, and grants) have no purchasing power, the city needed an emergency infusion of cash in 2009 from the Obama stimulus fund. In all, Gary received $266 million in stimulus funds [Gary, Indiana: Unbroken spirit amid the ruins of the 20th Century, BBC, by Paul Mason, 10-12-2010]:

I’d been to Gary, Indiana before. In April 2009, when the Obama fiscal stimulus had just begun, the city’s mayor had told me that all the city needed was $400m of stimulus money in order to “fly like an eagle and make our country proud”.

To put this in context you have to know that Gary, home to what is still US Steel Corp’s biggest plant, is suffering from one of the most advanced cases of urban blight in the developed world. Its city centre is near-deserted by day. The texture of the urban landscape is cracked stone, grass, crumbled brick and buddleia.

Gary is one third poor, 84% African American, and has seen its population halve over the past three decades. If crime, as the official figures suggest, has recently dropped off then – say the critics – that is because population flight from the city is bigger than the census figures show.

Gary in the end got $266m of stimulus money and has, according to the federal “recipient reported data” created a grand total of 327 jobs. That’s $800,000 per job.

I went back determined to find out how the stimulus dollars had been spent; to get beyond the ideology and recriminations and see why President Barack Obama’s stimulus has failed to turn the country around.

Brink of bankruptcy?

So what’s the story with Gary and the stimulus? The mayor believes the city is “last in line” when it comes to federal money – because the money is dispensed via the state of Indiana, which is Republican controlled. Mayor Rudy Clay tells me:

“I guess they thought, well, Gary voted in large numbers for the president, enabling him to take the state of Indiana, so he will look after them.”

But it is more complex – Gary’s public finances are a mess. It owes tens of millions of dollars to other entities. Its great get-out-of-jail card – tax revenue from casinos – turned out to be a busted flush. Its convention centre is dark most of the time. The one-time Sheraton Hotel, right next to the City Hall, is derelict.

With no ability to raise a local income tax it is reliant on property tax. But the State of Indiana passed laws capping tax raising powers, so by 2012 Gary’s tax income from property will halve.

At that point, according to the fiscal monitor appointed by the city, it will lack the revenue to fund even its police, fire and ambulance services. The monitor calls for much of the rest of Gary’s services to be privatised – but as city officials point out, once privatised they cannot enforce job guarantees that allow the city to employ local people. Says the monitor, bluntly:

“The city will simply have to give up some long-standing – and often important – services that are the responsibility of other governments, even when it is likely that those governments will not provide the same level of service.”

This is the cost of “Manifest Destruction.” Gary isn’t suffering from Urban Blight–that’s just a symptom of the real problem. It’s not suffering from crime, high foreclosure rates, bad schools, or lack of outside capital investment in the infrastructure (and potentially investors who would open up businesses that could provide some semblance of a commercial tax-base); it’s suffering from the unmentionable legacy of the migration of Black people and the overwhelming of a once prosperous white city.

Earlier this year Karen Wilson-Freeman became the first Black female mayor of Gary. Her goal? Increase the efficiency of the almost entirely Black-run government, which calls “small victories” fixing potholes, repairing sidewalks, and not dropping the calls the 84 percent Black constituents who call to complain about the poor city services [Meet Indiana’s First African-American Female Mayor, The Atlantic, 12-29-2011]:

While U.S. Steel still employs 6,000, that’s a far cry from the 50,000 people who once worked there, and the loss of those jobs is reflected in the boarded up homes and empty streets that spread across town.

At its peak in the 1950s, Gary’s population topped 200,000, only to plunge in subsequent decades to about 80,000 in 2010.

Freeman-Wilson says she wants to heal the sometimes tense relationship between employer and town. “Certainly, they have a responsibility to our city, but we have a responsibility to be a good partner,” she says.

To hold up its end, willing to start with “small victories,” like better lighting, pothole free streets and repaired sidewalks.

But beyond that, Freeman-Wilson speaks of making Gary a cleaner city, not only in appearance, but also in the way it deals with residents, who frequently complain they cannot reach anyone at city hall.

“You should be able to get through without being transferred five times,” Freeman-Wilson says.

The decline of Gary correlates to the rise of its Black population and the decline of the overall white percentage of its population (remember, roughly 100 percent white in 1920).

Indeed, where the white people went once they escaped Gary, prosperity flourished. Thriving business and commercial districts, safe streets, outside investments, and good schools were just an outgrowth of this migration [ Hurt feelings continue over Northwest Indiana town’s creation [Merrillville, Ind. experiencing now a little of what Gary did 40 years ago, WBEZ 91.5, 8-31-2012]:

U.S. 30 and Interstate 65 in Northwest Indiana is among the busiest retail corridors in Indiana. For a long time, this area, much of it in the Town of Merrillville, was the envy of Northwest Indiana, but none more so than for folks living in Gary.

To Steel City residents, the establishment of Merrillville a little more than 40 years ago was seen as a racist slap in the face allowed by Indiana state lawmakers.But today, if you need to buy a new car, or celebrate a birthday or buy that special gift or see a concert by a top-notch artist, if you live anywhere in Northwest Indiana chances are you’re doing it in Merrillville.

“Merrillville is the Main Street of Northwest Indiana,” said Rich James, a retired political columnist from Northwest Indiana.

While shops dominate the Merrillville landscape now, James remembers it wasn’t always like that.

“Fourty-one years ago, Merrillville was pretty much a cow pasture,” James said. “It had a name, it wasn’t incorporated.”

But what the area did have was plenty of open land; land to build homes and businesses on. This area became pretty attractive just as the City of Gary began its steep decline as steel jobs began to dry up in the once-thriving community of 175,000 residents.

But loss of jobs wasn’t the only issue facing Gary.

In the mid-1960s, blacks increased in number in what was then a very ethnic-white Gary.

Confined to living in one section of city for decades, blacks pushed for the right to live anywhere they chose, including in affluent white sections.

Richard Gordon Hatcher became Gary’s first black mayor in 1968. In the years up to his election, Hatcher pushed for an open housing law. It wasn’t easy.

“Every time it came up for a vote the council chambers would be packed with screaming and yelling. I liken them to the Tea Partiers today,” Hatcher told WBEZ. “They were yelling and all kinds of racial slurs and they would intimidate. I introduced that bill at least six times. It was defeated five times.”

White families from an increasing black Gary left in droves once Merrillville became a town.

The hurt from that time still exists today even as Merrillville’s demographics have shifted.

But it won’t last, with the Black Undertow escaping their city of Gary and migrating to wherever white people go. Merrillville is now 40 percent Black:

Merrillville incorporated as a town in 1971, developing at a rapid pace with not only new residents, but retail development over the next decade.

As life breathed into Merrillville, in Gary, it was just the opposite.

Residents fled and Gary’s once thriving downtown – devastated.

Carolyn E. Mosby remembers growing up in a rapidly deteriorating Gary and couldn’t understand why it was happening.

“When you see these boarded up buildings on Broadway or you see these vacant homes, a lot of the people who chose to leave, a lot of the people who chose to leave didn’t decide to sell their businesses or sell their homes, they just boarded them up and left,” Mosby said.

By the 1980s, Mosby was a teenager who often found herself not shopping at the Merrillville area’s new mall or other stores – pretty much at the insistence of her late mother, Carolyn B. Mosby, a longtime state legislator from Gary.

“She was very involved in the community as well and this was something that was very near and dear to her was to really support those people that chose to stay in Gary, the businesses and the folks who didn’t abandoned their home and moved to Merrillville,” Mosby said.

Just last year, Merrillville celebrated 40 years as a town.

This town of 35,000 residents is no longer lily white.

In fact, it’s now more than 40 percent African American, with many continuing to move because its school district is considered better than Gary’s.

No town in America is safe from the Black Undertow. Gary was overwhelmed, to the point where without the infusion of $200+ million of stimulus funds in 2009 it would have ceased to be a city. This is the legacy of the Black Migration from the South, an event that has led to the ruin of Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and decentralized the Black dysfunction that was once reserved solely for slave-holding states.

But it was in reading S. Paul O’Hara’s book that the realization that the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer U.S. Supreme Court ruling (outlawing restrictive covenants) was the nail in the coffin for the long-term prospects of America became crystallized. On p. 138 of Gary, the Most American of All American Cities we learn that the election of Gary’s first Black mayor signaled the coming of disaster for the white residents of the city:

Fear of a city run by a black mayor led many white residents to move away. “For Sale” signs popped up as residents feared declining property values. A rash of white flight of both capital and population occured. “I been here all my life,” reported one white resident to Harper’s.

I got me a house I paid $35,000 for, but I’m leavin’ it…. It’s not that I hate the colored or anything, but I’m dumpin’ it all. Who the hell wants to live this way, I ask you. Bein’ scared somebody’ll hit you on the head all the time, you can’t go out of the house after dark. You work all your life for something, and then they start movin’ in, and suddenly you don’t have anything – it’s not yours anymore. First person that makes me any kind of half-ass offer on that house now, it’s his, and I’m gone. With once exception – I’m not sellin’ to no goddam colored. I’d put a torch to it first.

The prospect of sharing a neighborhood, especially for a city built upon an image of strict separation, was seen as undermining the very thing people had worked for in the mills. “Mr. Hatcher, We are a big group of women, who would like to know a few answer,” stated one letter to the new mayor:

We have nothing against the colored people but we would not like to have them live next door to us. Yet it seems that the colored people are always pushing… Please can you explain to us why black people want to be near us when we don’t want them deep from our hearts & never will?

Questions that will never, ever be answered. Instead, billions upon billions of stimulus must be spent to try and “save” cities like Detroit and Gary–the reason being that “Manifest Destruction” destroyed the social capital, community, and infrastructure that white people had created before their arrival.

Without restrictive covenants, the future of all American cities resembles that of Gary, Indiana.

It is, after all, the most American of All America Cities: In Black-Run America (BRA) that is.

And like that fistful of sand from the Rod Stewart song, civilization in Gary has slipped through the hands of the Black people who inherited the city after whites left.