America’s First Race War?

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, June 26, 2020

European people living as minorities often develop a “bunker mentality,” or a belief they are always subject to attack. Colonel Reginald Dyer, the Anglo-Indian commander of mostly Gurkha and Muslim troops who committed the Amritsar Massacre of 1919, is an often-cited example of the bunker mentality in British India. Dyer and others of his generation grew up with tales of the Sepoy Mutiny and the Bibighar Massacre [1]. The French settlers in Algeria had a similar outlook; today’s white South Africans do as well.

In colonial New England, the Puritans, in their small settlements on the Atlantic coastline, felt the same way. They had many enemies: the French in Canada and their American Indian proxies, the Dutch in New York and their Indian proxies, and the tribes of New England, such as the powerful Narragansett. King Philip’s War (1676-1678) was the explosion of racial violence the Puritans had long feared. The New Englanders won, but at a cost of approximately 800 dead out of an overall population of 52,000 (a death rate of 1,538 per 100,000) [2]. That is a higher percentage of the population than died during the American Civil War.

There is debate over what started King Philip’s War. It broke out after leadership of both Indians and Europeans was passed to a new generation. Metacom (who was also known as King Philip), was of Wampanoag royalty. His father, Massasoit, had started a long period of peace between his tribe and the New Englanders after befriending the Plymouth Colony when it was established in 1620 [3]. Massasoit and the generation of New England leaders who remembered his kindness died at about the same time. Without those bonds of personal friendship, suspicions and misunderstandings grew. English lust for land, as well as underhanded practices such as getting Indians drunk before doing business with them, made relations worse. Philip, as a new sachem, collected arms and made alliances with other Algonquin-speaking tribes in order to resist English encroachment [4]. He also put a seven-year moratorium on sales of land to the English.

King Philip

The immediate cause of the war was the murder of John Sassamon, an Indian convert to Christianity. Sassamon had warned Plymouth Colony Governor John Winslow in January 1675 that Philip was planning to attack outlying villages. Another Christian Indian, Patuckson, told colony officials that he had seen three of Philip’s men kill Sassamon for having leaked the plans [5]. The three were put on trial and 12 New Englanders and an auxiliary jury of Indians found them guilty; they were hanged. Indians claimed they were wrongfully accused, and tensions rose. On June 20, 1675, a band of Pokanoket Indians attacked the Plymouth settlement of Swansea [6].

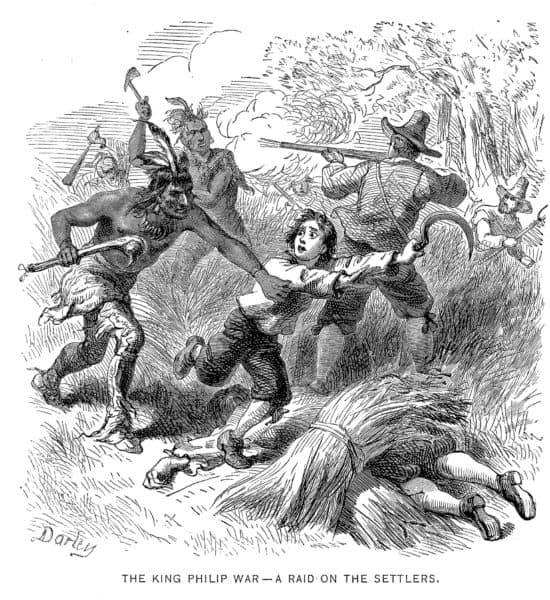

The war then began as both small-scale ambushes and attacks on towns and villages. When Indian raiders appeared carrying English-made muskets, residents of New England villages usually abandoned their homes and took refuge in garrison houses or fortified blockhouses. The Indians burned what the colonists left behind, thus destroying half of all towns between Maine (then part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony) and southern Connecticut [7].

For defense, the colonists relied mainly on the New England Confederation, a military alliance of Plymouth, Connecticut, New Haven, and Massachusetts Bay. Two historians of the war describe how the confederation’s units were organized:

By 1675, Massachusetts alone had some seventy-three organized companies. Each county maintained a dozen foot companies and one cavalry, while the counties of Suffolk, Middlesex, and Essex fielded a combined cavalry company. Each foot company contained about seventy privates and each cavalry about fifty. Muster days were held on a regular basis, although drilling could not compensate for the fact that New England’s defense was dependent on farmers unaccustomed to wilderness warfare [8].

The families that settled New England were not soldiers. They were from East Anglia, and came not as warriors but as religiously-minded merchants. John Winthrop, the leader of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the man with the authority to make decisions about violence, was reportedly a poor shot. Like their southwestern English brethren in Virginia, New Englanders hoped to establish a peaceful Protestant state in America that would be bi-racial and harmonious. They did not want to repeat the supposed evils of Mexico and South America, where Spaniards killed Indians and imported African slaves to do hard labor [10]. The Jamestown Massacre of 1622 put an end to such idealism in the Virginia colony, and King Philip’s War had the same effect in New England. The war became one of spasmodic and blundering ethnic cleansing.

The New England Confederation proved inept at putting down the insurgency. Plymouth and the colonies in Connecticut chafed under centralized rule from Boston, and New England militiamen often went home after fruitless patrols in the forests.

There was only one pitched battle: the Great Swamp Fight of December 1675. About 1,000 militiamen from the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut “attacked a large, fortified Narragansett village located in the Great Swamp (present-day South Kingston, Rhode Island)” [11]. The New Englanders killed almost 100 warriors and even more women and children, but lost about 70 men.

In a series of attacks in the northern theater of Maine, the Wabanaki and their allies killed as many as 400 colonists and drove the New Englanders out of every settlement except for Casco and a few other coastal enclaves.

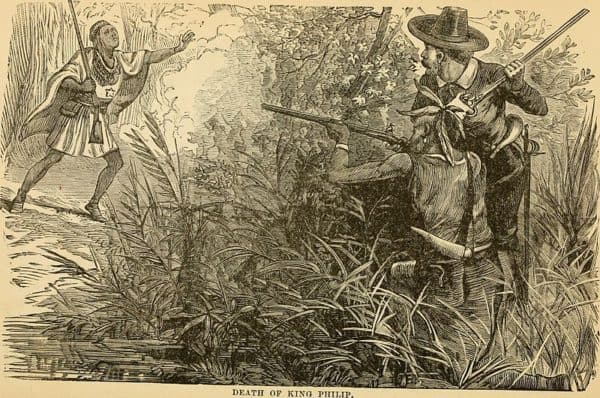

The English had only two competent commanders, Major Richard Waldron and Captain Benjamin Church. These men approached the war differently. Waldron, a rigid Puritan, was an experienced soldier and brutal to Indians. He conducted the many battles in Maine and New Hampshire, and tried to engage large numbers of Indians in European-style engagements. Church, on the other hand, who made a living as a carpenter, believed in maneuver. Unlike other New England leaders, he also believed in using Indian allies and training New England militiamen to fight like Indians. They moved in small units and specialized in ambush and raiding, making Church’s force the first Ranger unit in American history. It was his band of fighters that finally killed King Philip in August 1676, after a year and a half of warfare, though fighting in the north continued until April 1678.

Benjamin Church is often seen as the most prominent figure of the war, partly because he kept a diary. It describes his friendly relations with Indians (including what may have been a sexual relationship with a female sachem) and his frustrations with the Puritan establishment in Boston. It was very popular in the Early Republic. From the Revolution to the age of Jackson, Church was upheld as the quintessential American: a peaceful carpenter who took up his gun to protect his civilization [12]. Church later fought in King William’s War (1688–1697) and Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713) before dying at age 78 (some sources say 79).

King Philip’s War produced another eyewitness account. Mary Rowlandson of Lancaster, Massachusetts, was captured by Indian raiders on February 10, 1675, and held for 11 weeks and five days [13]. Rowlandson and her fellow New Englanders had to march through Massachusetts, southern Vermont, and New Hampshire. Her diary, later published as The Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, became an early best-seller. She described the Indian attack:

But out we must go, the fire increasing, and coming along behind us, roaring, and the Indians gaping before us with their guns, spears, and hatchets, to devour us. No sooner were we out of the house, but my brother-in-law (being before wounded, in defending the house, in or near the throat) fell down dead, whereat the Indians scornfully shouted, hallooed, and were presently upon him, stripping off his clothes [14].

Rowlandson was made the slave of an Indian leader and forced to listen to her captors boast of killing New England militiamen. She was finally freed, thanks to the women of Boston, who paid her ransom. Rowlandson was at least spared the fate of colonial New England’s other famous heroine, Anne Hutchinson. Banished from Boston for preaching Antinomianism, Hutchinson and her family moved to New Netherland. There, in the summer of 1643, Algonquians scalped her and her entire family during Kieft’s War (1643–1645). The Indians were seeking revenge against Dutch settlers but ended up killing English instead.

The story of King Philip’s War is the story of American survival. Although some have claimed that it led to a distinctive New England identity, it seems to have moved the colonists closer to the metropole. England returned the favor by sending more government officials but, at the same time, curtailing liberties that had been established by the original charters. By the time of the Revolution, Americans in the North and South saw themselves as British subjects and invoked King George III and the traditions of monarchy against the illegal activities of Parliament. The lesson of King Philip’s War is not that it created a separate American identity but that it established New England as a thoroughly English colony. No tribal alliance ever again seriously threatened Massachusetts or Connecticut, thus allowing for the full flowering of Anglo-Saxon culture.

Another important lesson of King Philip’s War is that every inch of New England — like much of America — had to be fought for and conquered. The Puritans suffered great loses but defended their towns and developed new ways of fighting. The war also foretold many conflicts to come, as Europeans clashed again and again with Indians as they moved South and West. The early history of the United States is no different from what we see today: the agony and tragedy of trying to build a mixed society of people of different races.

[1]: Mimi Matthews, “The Bibighar Massacre: The Darkest Days of the Indian Rebellion of 1857,” Mimi Matthews.com, 2018 Dec. 6.

[2]: Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias, King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict (New York: The Countryman Press, 2017): 5.

[3]: Schultz and Tougias, 1.

[4]: Philip Gould, “Reinventing Benjamin Church: Virtue, Citizenship and the History of King Philip’s War in Early National America,” Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Winter, 1996): 645.

[5]: Schultz and Tougias, 27.

[6]: Schultz and Tougias, 2.

[7]. Gould, “Reinventing Benjamin Church,” 645.

[8]: Schultz and Tougias, 21.

[10]: Alan Gallay, Walter Ralegh: Architect of Empire (New York: Basic Books, 2019): 6.

[11]: Schultz and Tougias, 53.

[12]: Gould, “Reinventing Benjamin Church,” 648.

[13]: Schultz and Tougias, 341.

[14]: Qtd. in Schultz and Tougias, 343.