Charles de Gaulle and the Idea of France

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, June 14, 2019

Julian Jackson, De Gaulle, Belknap Press: an Imprint of Harvard University Press, 2018, 928 pages, $26.80 Hardcover, $25 Kindle.

This biography of Charles de Gaulle by Julian Jackson prompted both the conservative Federalist and the leftist New Statesman to run articles called “How Charles de Gaulle Made France Great Again.” The general supposedly reconciled the political tribes of Left and Right into a “certain idea of France.” In Conrad Black’s words, he “settled the ancient argument between the monarchists and the republicans by creating a monarchy and calling it a republic.” He gave the French a myth of victory in World War II and disguised the country’s decline through a foreign policy of grandeur. With American identity fragmenting, Ross Douthat pleads for “A de Gaulle of Our Own.”

Yet de Gaulle would have no place in France today. He knew that the French were a people, not an idea.

Charles de Gaulle was raised in a conservative, Catholic family in a neighborhood of Paris — near the Invalides and the military school of St. Cyr — that was rich in monuments to French military history. He was influenced by the nationalism of monarchist Charles Maurras, but it was poet and essayist Charles Péguy who most influenced him. Péguy’s “ecumenical nationalism” aspired to a “synthesis of all French traditions,” in Prof. Jackson’s words. “The Republic, One and Indivisible, is our Kingdom of France,” wrote Péguy. This concept of nation above ideology defined de Gaulle’s career.

The general’s famous June 18, 1940 broadcast from London calling on the French to resist surrender after the fall of France appealed to national “honor and independence.” And his idea of France was not necessarily republican. For months, he refused to commit to democracy, and he did not publicly utter the words “liberty, equality, fraternity” until November 11, 1941, and that was only after he was accused of fascism.

The general’s first argument for continued resistance was that France “has a vast Empire behind her” — the “Free French” territories in the Pacific and Africa. The pseudo-state de Gaulle set up was called the “Empire Defence Council,” which he proclaimed in a manifesto issued from Brazzaville in the French Congo. Gaston Palewski, later a close confidante, initially mocked de Gaulle’s “n***er kingdom.”

De Gaulle defended French imperial interests during the war and tried to keep control of Indochina. He even flirted with war against Britain in January 1945, when Churchill ordered British forces to restrain the French from violently suppressing Syrian protesters. “We are not, I recognize, in a position to wage war on you at the moment,” de Gaulle stiffly informed British Ambassador Duff Cooper, “but you have outraged France and betrayed the West.” In his Memoirs, de Gaulle spoke of France’s “civilizing mission” in the Levant.

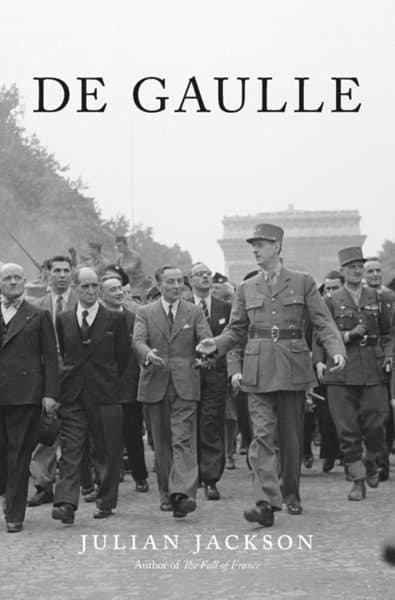

Charles de Gaulle’s most iconic moment was leading the massive march on August 26, 1944 through the streets of Paris after the liberation. He became head of government in November 1945, and wanted to promote immigration — of Europeans. Prof. Jackson writes that “he came down on the side of controlled immigration to limit the ‘influx of Mediterranean and Orientals’ and to encourage those from northern Europe.” De Gaulle resigned just over a year later because he thought he did not have enough executive power. His “Rally of the French People” movement, united by his personality, never quite got the majority it needed to bring him to power and dissolved in 1955. But even in retirement, de Gaulle was certain that in a crisis, France would once again seek his leadership. That crisis came in 1958.

In May, the pied-noirs or French-Algerians staged a coup against control from Paris. French paratroopers from Algeria even seized Corsica, and politicians, fearing civil war, restored de Gaulle to power. The general dismissed fears of fascism, declaring, “Do you think that at sixty-seven I am going to begin a career as a dictator?” Within a few months, the newly written Fifth Republic constitution gave de Gaulle the broad executive powers he had always wanted.

October 3, 1958 – Charles de Gaulle during his visit to Algeria. (Credit Image: © Keystone Press Agency/Keystone USA via ZUMAPRESS.com)

“The question remains: how deep was de Gaulle’s complicity in the Algerian insurrection?” asks Prof. Jackson. A few years later, de Gaulle denied involvement in what he called an “enterprise of usurpation from Algiers.” “I did not raise a little finger to encourage the movement,” he said. Prof. Jackson calls this “superb disdain for the facts.”

On June 4, in a display of strategic ambiguity, de Gaulle declared to a crowd in Algiers, “I have understood you,” leading them to believe he would never give Algeria independence. However, de Gaulle also offered reconciliation to Algerian rebels and promised equality for Muslims and Europeans. He did not utter the phrase “Algérie française” (French Algeria) in Algiers — but he did two days later in the Algerian port city of Mostaganem — only after some hesitation. Prof. Jackson claims the video of the speech was edited by “propaganda services of the army” to remove the hesitation.

“Algérie française” supporters wanted complete national “integration” with France. “The nine million Muslims, who were a majority in Algeria,” writes Prof. Jackson, “would be a controllable minority once ‘integrated’ into a wider electorate of forty-five million French voters.” Many would consider “Algérie française” supporters to be on the “Right.” Yet de Gaulle’s rationale for opposing it would today be called “far right.” He thought integration was suicidal, and called people who supported it “asses:”

Have you seen the Muslims with their turbans and their djellabas (traditional, hooded, long wool coats)? You can see that they are not French. Try and integrate oil and vinegar. Shake the bottle. After a moment they separate again. The Arabs are Arabs, the French are French. Do you think that the French can absorb ten million Muslims who will tomorrow be twenty million and after tomorrow forty? If we carry out integration, if all the Berbers and Arabs of Algeria were regarded as French, how would one stop them coming to settle on the mainland where the standard of living is so much higher? My village would no longer be called Colombey-les-deux-Eglises [the two churches] but Colombey-the-two-mosques.

Prof. Jackson notes that de Gaulle “was skeptical about integration because his beliefs were not grounded in that progressive tradition according to which the universal values of French republicanism had created a community of equal citizens superseding racial or ethnic identities.”

Jacques Soustelle, an anti-fascist, former member of the Free French, and a supporter of de Gaulle’s return to power, called the general’s views “racist.” Soustelle later joined the “Secret Army,” the OAS, usually called a “right wing terrorist group” that fought against Algerian independence. “Right” and “Left” are often misleading labels when it comes to racial issues.

De Gaulle wanted military victory before coming to a settlement in Algeria. He also resisted negotiating with the National Liberation Front (FLN) or the Algerian revolutionary movement. He privately told a group of officers he would “never” negotiate with the FLN. Yet he ultimately did.

In January 1961, French voters approved a referendum calling for self-determination for Algeria. On April 11, 1961, de Gaulle said, “France would contemplate with the greatest sangfroid a solution by which Algeria would cease to belong to her.” A little over a week later, there was an attempted coup by military men who refused to give up Algeria. In full military uniform, General de Gaulle furiously denounced the coup on television and swiftly suppressed it. On July 3, 1962, following negotiations and referendums in both France and Algeria, de Gaulle declared Algeria an independent country.

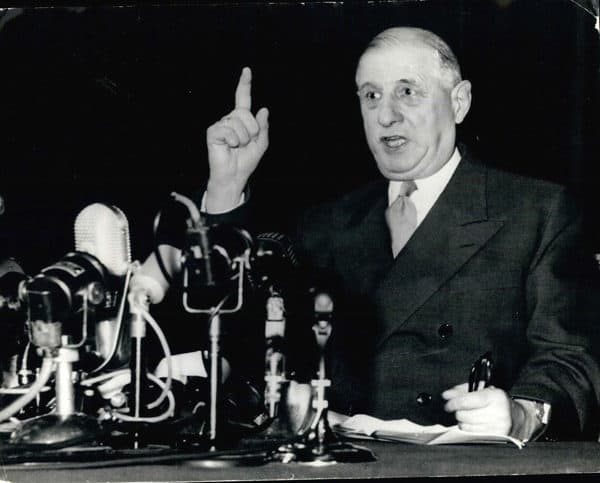

General De Gaulle, seen as he made his long awaited speech at the Hotel Palais D’Orsay. This was his first speech since he said he was ”ready to take over” following the crisis on the Algerian question. (Credit Image: © Keystone Pictures USA/ZUMAPRESS.com)

De Gaulle was mostly indifferent to the pieds-noirs. He dismissed the idea of reserving part of Algeria for Europeans, calling it a “French Israel.” “At least the Israelis fought for their independence after having conquered it,” he said. After Algerian independence — and after the massacre of Europeans in Oran — almost a million pieds-noirs fled to France, a country many had never seen. When told many were suffering in makeshift camps, de Gaulle brutally said, “None of this would have happened if the OAS [the anti-independence “secret army”] had not been able to operate among them like a fish in water.”

However, de Gaulle at least recognized France could absorb the pied noirs — not the Harkis, or Arabs who fought for the French. “No Harki must be allowed to embark for the Metropole [France] without the express and formal approval of the Minister of the Armies,” he instructed. “Any Harki who within 8 days has not accepted the job offered to him must be sent back to Algeria. The actual number of Harkis in the Metropole must not increase.”

Prof. Jackson also quotes de Gaulle saying, “I would like there to be more French babies and fewer immigrants.” As early as 1916, when he was a young officer in First World War, when de Gaulle heard his sister had given birth, he wrote his mother that “beautiful little French babies are going to be necessary to replace those who have died for the Fatherland.”

Prof. Jackson says de Gaulle had a “seeming immunity to the anti-Semitism that was such a feature of French society at this time,” though the general made occasional anti-Semitic remarks. “I do not know differences of race or political opinion among us,” he said during the Second World War. “I know only two kinds of Frenchmen: those who do their duty and those who do not.”

However, General de Gaulle’s “idea of France” had a religious component. “What is certain is that de Gaulle’s Catholicism was inseparable from his patriotism and sense of France,” writes Prof. Jackson. “For me, the history of France begins with Clovis, elected as king of France by the tribe of the Franks, who gave their name to France,” said de Gaulle. “My country is a Christian country and I reckon the history of France beginning with the accession of a Christian king who bore the name of the Franks.” His declaration that Muslims were “not French” is further evidence of such views.

“It is very good that there are yellow Frenchmen, black Frenchmen, brown Frenchmen,” de Gaulle wrote in a private letter in 1959. “They prove that France is open to all races and that she has a universal mission. But on condition that they remain a small minority.” He added: “Otherwise, France would no longer be France. We are, after all, primarily a European people of the white race, Greek and Latin culture, and the Christian religion.”

Charles de Gaulle would be horrified by today’s immigration crisis. He wanted to give Algeria independence because he wanted separation from the Arabs. “The incompatibility of the French and Algerians is what explains and justifies what I have called withdrawal,” he said to France’s first Ambassador to Algeria. “As for Algerian immigration,” he continued, “enough of that.” Whatever his faults, Charles de Gaulle understood that his “idea of France” was rooted in a specific French people with a defined culture and shared history.

Julian Jackson’s biography begins with a reference to the many memorials to the general: “In France today, Charles de Gaulle is everywhere.” The same could be said of the American Founding Fathers — and their position in the long term is no more secure. To a resentful banlieue resident, de Gaulle means no more than George Washington does to the people of East St. Louis. There can be no “idea of France” without the French themselves.