You Got Raced

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, April 20, 2018

In a recent piece, Slate’s Jamelle Bouie explained that the two African-American men recently arrested at the Starbucks in Philadelphia had been “raced.” “Race is about power and hierarchy,” claims Mr. Bouie. “When one is ‘raced,’ one is placed in relationship to that hierarchy — your position assigned to your body and made visible to the world.” A place also can be “raced,” says Mr. Bouie, and when blacks enter a “white space” like the Philadelphia Starbucks, blacks are perceived as a threat.

Mr. Bouie bases his analysis on sociologist Elijah Anderson, who penned “The White Space” for Sociology of Race and Ethnicity in 2015. Dr. Anderson’s piece mostly recounts subjective, anecdotal experiences and uses them to justify sweeping assertions. He argues that blacks who enter “white spaces” are immediately distrusted as a dangerous foreign element. Thus, middle class blacks must perform what some call a “dance” to show ghetto stereotypes do not apply to them. Examples of this “dance” include dressing well, using sophisticated language, or providing identification when whites are not required to do the same.

Contra Dr. Anderson’s assertions, white people do not behave like those in Eddie Murphy’s Saturday Night Live sketch, beginning elaborate celebrations the second the last black person leaves the room. It’s doubtful a white person even notices how many black people are in a restaurant or bar. Nor would the typical upscale restaurateur turn away a well-dressed black customer to joyfully welcome a white man dressed in a dirty sleeveless shirt.

Whites are certainly self-conscious if they are in a mostly black space, the same way Dr. Anderson is about being in a mostly white space. However, what he regards as a “dance,” most whites regard as basic social norms that make them feel comfortable. More importantly, while Dr. Anderson and other blacks claim to worry about possibly being hassled or judged in a “white space,” whites are generally more concerned about their physical safety in a “black space.”

A “black space” in Philadelphia.

Yet Dr. Anderson claims blacks are in a position of danger and terror in “white spaces.” He writes:

When a racial epithet, or the attitude underlying it, is expressed, it tells the black person directly that he does not belong. As one black informant observed, ‘Once it happens to you, all bets are off, and you do not know what to expect, no matter what you thought of yourself; for the moment, you don’t know just where you stand. You feel like a stranger in a strange land.’

Almost any white person present in the white space can possess and wield this enormous power.

Of course, what Dr. Anderson calls a “white space” is no such thing. A mostly “white space,” usually established by economic requirements, is far different than an explicit white space by, for, and about white people. Indeed, any conscious attempt to maintain a real “white space,” even verbalizing a desire for one, will be fiercely punished by the same institutional power structure Dr. Anderson claims supports white interests.

More importantly, Dr. Anderson has the power situation precisely backwards. White people are not in a position of “enormous power” in these situations, but powerless. Whites are at blacks’ whims. If blacks go through the “dance” of upholding white middle class social norms, it’s because they want those norms upheld too.

If a black person forces a confrontation and it is caught on video, he can count on support from the media, ethnic lobbies, and progressive organizations. Whites are extremely conscious of and sensitive to accusations of racism, not simply because of the perceived moral connotations, but because of the disastrous economic and social consequences of being labeled “racist.” Therefore, blacks have the power to violate social customs, start unnecessary arguments, or even make threats without being called to account.

For example, if a white man is being loud and disruptive at a public place such as a restaurant, he may be expelled. That will be the end of the incident. However, if a black man is being loud and disruptive, the calculation changes.

To accuse a black man of being loud or disruptive may draw accusations of racism. Whites therefore tolerate the disruption to avoid a showdown which may cost them their job. Of course, this means abandoning certain standards of behavior, what Dr. Anderson seems to deride as a “dance.” Calling the police is no escape, as the black person can simply claim he wasn’t doing anything and thus create even more controversy.

In other words, a “white space” exists only at the sufferance of blacks. If blacks choose to enter a “white space” and violate the behavioral norms of that space, there isn’t much white people can do about it. The reason, of course, is that the institutional power structure — meaning the courts, media, and politically powerful organizations — will not be on the side of whites.

(Credit Image: © Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

Using physical force in such situations to expel misbehaving blacks is unthinkable for similar reasons. Expelling a disruptive white person is business as usual; expelling a black person would become “racist assault.” Dr. Anderson says bouncers often approach blacks with a “disingenuous” question, “Can I help you?” He argues this is interpreted by young black men as “What is your business here?” Yet even in predominantly white areas, bouncers at spaces such as bars and concert venues are often black themselves. One suspects the reason is because blacks can expel other blacks without drawing accusations of racism. As a kind of bonus, black bouncers can more easily persuade excitable whites to leave, as few whites want to start fights with them and be accused of racism or even a hate crime.

Even when a white person does use what Dr. Anderson alleges is his “enormous power” of making a black person feel unwelcome, it is often a windfall for the black victim. If caught on video, being the subject of a “racist” verbal attack automatically turns a non-white into a figure of sympathy. Indeed, the desire to be a victim and reap the rewards that go with it is likely driving the many fake hate crimes.

Blacks know this, which is why they have no fear of forcing confrontations in certain situations. This may be what happened in the Starbucks incident. According to an initial statement by Commissioner Richard Ross of the Philadelphia police, the two black men at the Starbucks had told employees, “Go ahead and call the police, we don’t care” and repeatedly refused officers’ instructions to leave the store. According to Commissioner Ross, “There is also some alleged rhetoric [from the black men to the police] that you don’t know what you’re doing, you’re only a $45,000 a year employee.”

This does not necessarily mean calling the police was the right move by the Starbucks manager. However, almost every white person would either buy something or leave the store if confronted, would be desperate to avoid a police confrontation, would not refuse the police, and most importantly, would not expect public sympathy and support for defying or insulting police officers. Blacks understand the power calculation is different and act accordingly. They are right to do so; Police Commissioner Richard Ross has already reversed himself and apologized to the black men. This means either his initial account is a lie (or that his officers lied to him) or that he is backing down for political reasons. The latter seems more likely.

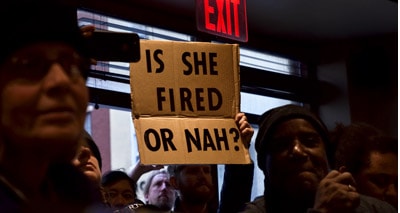

Jack Willis leans on a sign that reads Coffee Is Black as protesters gather at the Starbucks location in Center City Philadelphia. (Credit Image: © Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

At worst, Starbucks manger Holly Hylton acted too rashly to call the police. Yet she is now receiving hostile coverage from major media outlets, and activists are demanding she be punished. A former employee who worked under Miss Hylton, one Ieshaa Cash, is accusing her of racism, and will likely profit by doing so. Even those who claim to be conservatives are recycling these accusations of “racism.” Thus far, no one has been willing to defend Miss Hylton publicly, and probably no one will. Her physical safety is probably also in danger, at least in the short term.

In contrast, for the two black men who were arrested, this may be the greatest thing that has ever happened to them from a career standpoint. They are not facing charges, so they have no legal worries. Rashon Nelson and Donte Robinson (along with their attorney, Stewart Cohen) told their story on ABC’s Good Morning America, and their version was quite different from what Commissioner Ross said happened. As the commissioner is already groveling before them, that is the version which will stay in the public mind. They are established as victims — the most lucrative status to hold. Whatever “real estate” deal they were supposedly going to discuss at the meeting, this whole experience will probably be far more profitable for them.

The same cannot be said for Holly Hylton. Or Justine Sacco. Or the countless others who have had their lives destroyed after being accused of racism. Until now, there wasn’t even a word for what happens to white people like them. Thanks to Mr. Bowie, now we have one. What happened to them shows the reality of power and hierarchy in multiracial America. They got “raced,” and they were destroyed.