The Chinese Uprising Against Whites

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, December 29, 2017

Kill the foreigners and the mandarin beasts. There will be no hope for the common people until the foreigners and mandarins are gone.

— Battle cry of the “Boxers.”

In China, they are known as the Yihequan, or the Fists of Harmony and Justice. In the West, they are known as “Boxers,” a name that comes from their practice of Chinese martial arts and other rituals that supposedly made them impervious to Western weapons. In 1900, these suicidally brave fighters laid siege to Peking (Beijing) and Tientsin (Tianjin) for over a month, while a loose coalition of European, Japanese, and American troops scrambled to protect their resident citizens. The coalition succeeded, but the Boxer Rebellion, which began as an anti-white and nationalist movement, played a large role in priming East Asia for a global confrontation.

Ever since the two Opium Wars of the mid-19th century, China had been carved up by European powers, primarily the British and French. While the ethnically Manchu Qing dynasty remained in ostensible control and no parts of China were colonized outright, Europeans dominated Chinese trade and industry through extraterritorial concessions. A series of droughts and floods in 1898 and 1899 made conditions worse for Chinese peasants in the north, and many gravitated towards the Boxer movement.

As noted in Diana Preston’s The Boxer Rebellion, the Boxers were a secret group that had its origins in various anti-Manchu movements that sought to establish a Han royal family. However, as northern China descended into increasing anarchy, the anti-Manchu societies began blaming the “white devils” rather than the Qing for their misfortunes.

Neoconservative Max Boot writes in his book The Savage Wars of Peace that the rebellion “resembled other millennial movements elsewhere . . . among peoples whose traditional way of life was crumbling before the onslaught of modernity.” In this case “modernity” meant Western civilization, Christianity, and white people themselves. Mr. Boot compares the Boxers to the Mahdists of Sudan and the Sioux Ghost Dancers of the American West.

By 1898, the primary Boxer slogan was “Support the Manchus, Destroy the Foreign.” In Shantung Province, Boxer placards read: “Heaven is now sending down eight million spirit soldiers to extirpate these foreign religions, and when this has been done there will be a timely rain [to end the drought].” For the Boxers, white foreigners were “Primary Devils,” Chinese Christians were “Secondary Devils,” and all non-Christian Chinese who collaborated with the foreigners were “Tertiary Devils.”

Anti-white, anti-Christian violence started decades before the full-scale rebellions of 1900.

In 1870, hundreds of Chinese attacked an orphanage run by the French Catholic Sisters of Charity after several Chinese orphans died from an unknown disease. Many Chinese at that time practiced traditional medicine that used wild animal parts — the kind of traditional medicine that threatens the world tiger and rhino populations today. The attackers believed that the Europeans made medicine out of the hearts and eyes of the children and that the French nuns were guilty of removing fetuses from Chinese women in order to practice Western alchemy. In its fury, the mob raped sixteen of the orphanage’s nuns, chopped them into pieces, and threw them into the flames of the burning orphanage.

On All Saints’ Day in 1897, Boxers hacked two German Catholic priests to death. A third managed to survive despite being repeatedly stabbed and slashed. On December 31, 1899, Boxers killed and decapitated the British missionary Sidney Brooks. Other such attacks plagued northern and central China up until the rebellion of 1900. For Europeans, the Boxers represented the “savagery” of the East that needed to be conquered by Christian civilization. An armed confrontation was inevitable.

Diana Preston notes that Europeans generally held Chinese in disdain. Citizens in the various legations in Peking wrote in letters and journals of the filth of the city and its citizens. They often used phrases such as “the worst smells imaginable,” “dusty and malodorous,” and “disgusting.” Missionaries and diplomats often treated Chinese haughtily.

Boxers finally rose up in earnest in early 1900, and by May they had surrounded Peking. Hundreds of European, American, and Japanese citizens — including women and children — were trapped. Chinese Christians also found refuge in the besieged legation quarters and the few Christian churches manned by foreign troops in Peking. They brought accounts of Boxers killing Christians and burning churches. By June 13th, the Boxers were in full control of Peking — except for the foreign quarter — and pillaged the city. They chanted “Sha! Sha!” (Kill! Kill!) as they burned Christian churches and destroyed European shops.

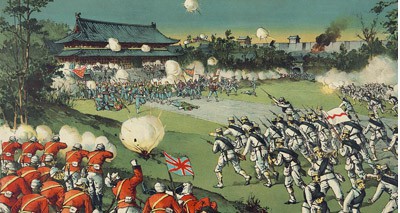

A Boxer during the revolt.

The “yellow” presses of America and Great Britain falsely reported in July that 1,800 white men, women, and children had been tortured, murdered, and mutilated. Editors demanded a firm response to these fabricated atrocities, and goaded a coalition into being.

The reaction in the West was typified by leaders such as Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. He evoked the “yellow peril,” or the belief that rising Chinese birthrates and waves of Chinese immigration to Australia, Canada, and the United States were a threat to Western civilization. Here is part of the Kaiser’s message to his men when he sent then to China in 1900:

A great task awaits you: You are to revenge the grievous injustice that has been done. The Chinese have overturned the law of nations; they have mocked the sacredness of the envoy, the duties of hospitality in a way unheard of in world history. It is all the more outrageous that this crime has been committed by a nation that takes pride in its ancient culture. Show the old Prussian virtue. Present yourselves as Christians in the cheerful endurance of suffering. May honor and glory follow your banners and arms. Give the whole world an example of manliness and discipline.

Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated! No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! . . . [M]ay the name German be affirmed by you in such a way in China that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German.

Leaders from London to St. Petersburg spoke in similar terms while the American and British press penned lurid stories about crimes against Westerners by bands of Boxers.

Richard Bassett notes in For God and Kaiser that Austro-Hungarian sailors were the first to come over fire in the defense of Peking — even before the relief missions set out. Typically portrayed as cowardly or incompetent, the sailors of the Dual Monarchy (almost all of whom were ethnic Croats) brought a Maxim machine gun to the battle and did much to shore up weak French and Belgian defenses. With only 420 men in total, the Austro-Hungarians repulsed thousands of Boxers and uniformed Chinese troops who had joined the rebels. Elsewhere, hundreds of British, French, Belgian, German, Japanese, and Russian legation guards tried to keep the Boxers out of the foreign quarter.

The first major relief effort from the West was the Seymour Expedition. On June 10, 2,100 hundred British sailors and 112 US sailors and Marines led by Admiral Edward Seymour were sent towards Peking but the small Anglo-American force was harried by Chinese troops and was unable to move effectively on Peking. Seymour had to be rescued by an allied force of 1,800 men and fell back to Tientsin, which was not captured until July 14.

Combined British, Italian, German, Russian, American, Japanese, and Austro-Hungarian forces moved towards Peking, while their compatriots in the foreign quarter managed to withstand the Boxer siege for a total of 55 days. They were finally relieved on August 15.

Foreign Troops Entering Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion, circa 1900 (Credit Image: © Glasshouse/ZUMA Wire)

The battles for Peking and Tientsin eerily presaged World War I and the difficult art of coalition warfare. In some instances, the coalition barely functioned. When an initial march on Tientsin began on June 4, 1,700 Russians decided to leave their allies behind in order to take the city by themselves. Their ill-advised rush into battle was halted by 50,000 enemy troops, many of them Chinese Army regulars. The Russian retreat was covered by 140 U.S. Marines commanded by Littleton Waller. Four enlisted men earned the Medal of Honor for their part in the running firefight.

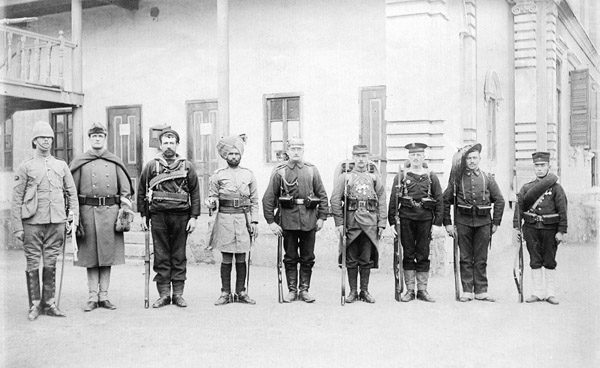

“Troops of the Eight nations alliance of 1900 in China. Left to right: Britain, United States, Australia, India, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan.”

Other notable men included Marine Private Dan Daly, a future winner of two Medals of Honor. During the siege of Peking, Daly spent an entire night by himself on a defensive wall. With just a 6mm Lee Navy rifle, Daly managed to fend off hundreds of Boxer and Qing troops. When he was relieved the next day, he told fellow Marines that the Chinese had called him quonfay (“devil”) all night long. Another plucky American was Corporal Calvin P. Titus of the 14th Infantry. At Tung Pien Gate outside of Peking, Titus scaled the wall by himself and held down Boxer and Qing troops with rifle fire. This allowed fellow soldiers to enter the city and break the siege.

Marine Private Dan Daly

The Boxer Rebellion played an outsized role in the course of geopolitics between 1900 and 1945. As part of the $335 million dollar indemnity imposed on the Qing Empire by the victorious allies, the Russian government decided to take Port Arthur and occupy all of Manchuria. This in turn angered Tokyo, which sought to expand Japanese economic power throughout East Asia. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 not only helped to cause the proto-Bolshevik revolution of 1905, but it also showed Asians that white soldiers were not invincible. During the Second World War, Japanese further damaged the image of the white man by dehumanizing captured Allied POWs and white civilians.

The Boxer Rebellion also opened up a historical wound on the Chinese psyche. Chinese students today still learn about the foreign soldiers who committed sacrilege by marching through the Forbidden City. The Chinese Communist Party also used the example of the Boxers to encourage the depredations of the Red Guards. During the Cultural Revolution, which may have killed as many as two million Chinese citizens, Chinese communists sang songs about ridding China of all foreigners. Like the Boxers before them, the vanguard fighters of the Cultural Revolution participated in a peasant uprising predicated on superstition and a belief in a false religion (this time communism instead of folk customs).

Chinese see the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion and the entire 19th century as an age of shame. In order to avenge that shame, China must again reclaim its proper place as the “Celestial Kingdom.” The Chinese Communist Party spent the 1960s and 1970s giving guidance, weapons, and money to anti-Western insurgencies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. China is not likely to use its increasing power and influence to the benefit of the increasingly beleaguered West.