The Fortunes of Africa

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, May 15, 2015

Martin Meredith, The Fortunes of Africa: A 5000-Year History of Wealth, Greed, and Endeavor, Public Affairs, 2014, 784 pp., $35.00.

It is not easy to fit 5,000 years of the history of anything between two covers, much less the history of an entire continent. Journalist and historian Martin Meredith has not only done it, he has done it very well. The Fortunes of Africa is a first-rate introduction to a part of the world about which most Americans know next to nothing, and is an excellent companion to Mr. Meredith’s masterful account of black Africa since independence, The Fate of Africa.

Like the previous volume, this one is marvelously unsentimental. Mr. Meredith has no use for fantasies about mythical black sages and empires, nor does he make a fetish of the sins of the white man. He just tells the story–and it is a fantastic tale of colorful characters and useful lessons.

Recurring patterns

Although the author does not always call attention to them, there are clear patterns that emerge from this history, one of which is the importance and persistence of slavery. Except among people such as the Pygmies and Hottentots who were so poor that they were all struggling to survive, slavery was practiced all across the continent for as long as we have records.

Foreign peoples who came into contact with black Africans appear to have found them deeply alien and fit candidates for slavery. Place names that persist to this day reflect what must have been the first reaction of all outsiders on first meeting blacks. “Sudan” by which was meant the entire south Saharan region, comes from the Arabic Bilad as-Sudan, meaning “land of the blacks.” “Guinea,” which is in the names of three African countries as well as the gulf of that name, comes from a Moroccan word meaning “black.” “Ethiopia” comes from the Greek, meaning “burnt faced.” Zanj, which is the Arab name for the east coast of Africa and for its inhabitants, means “black.” Likewise, “Zanzibar” is from the Persian, and means “black coast.”

For centuries, black Africa had only three major exports: gold, ivory, and slaves. When trade caravans began crossing the Sahara in the 8th century, they brought slaves north. Mr. Meredith notes that the service life of early trans-Saharan slaves was about seven years, so there was steady demand. A good horse could be traded for 10 to 30 slaves, and eunuchs brought the highest prices. From 600 to 1500 AD, before the trans-Atlantic trade began, there were probably some 4 million slaves taken across the Sahara to markets in North Africa and the Middle East. Enslavement of blacks was so common that the Arab word abd, which means “slave,” (the name Abdullah means “slave of Allah”) also meant any black person.

Muslim Arabs tried to conquer the black Christian kingdoms in the highlands of what is now Ethiopia (missionaries from Alexandria had converted them in the fourth century). The Christians fought the Muslims to a standstill and established a truce, under which there was to be an annual exchange. The Arabs would supply horses, wheat, etc., in return for 360 of “the finest slaves of your country,” both male and female. Mr. Meredith writes that this deal, known as the Baqt, was honored for six centuries.

For about 800 years, Muslims shipped slaves from the east coast of Africa. Zanzibar is only 20 miles off the coast of Africa, but sea-faring Arabs controlled the island, and Islam was firmly established by the 11th century. From bases in Zanzibar, Arabs controlled a vast, East African slave and ivory trade, with destinations throughout the Middle East. During the 1860s, after the trans-Atlantic trade had been essentially abolished, Zanzibar was still shipping out some 20,000 slaves and 250 tons of ivory every year.

Stone Town, on Zanzibar, was the world’s last public slave market. The British shut it down in 1873, but could not root out the system, and Arab traders continued to hunt slaves in the interior to work on plantations on the coast. In 1875, the British Navy had to put down several local rebellions by slave traders on the coast who were furious that outsiders were meddling in their business. Mr. Meredith notes that British interference resulted in a sharp rise in the price of slaves.

It was the Portuguese who began the Atlantic slave trade in 1441, initially supplying markets in Portugal and Spain. Henry the Navigator initially promoted exploration of the African coast in the hope of finding a sea route to the gold mines in what is now Ghana, but slaves turned out to be a more accessible commodity. Since slavery was widely practiced in West Africa, the Portuguese had no trouble finding suppliers, and rarely had to go on slaving expeditions themselves. The Spanish church sent missionaries to the Congo delta, where profits were so high that even priests traded slaves.

In many African kingdoms, the punishment for crimes such as murder or theft was enslavement, and chiefs were happy to sell off their criminals to Europeans. A horse could be had for 9 to 14 slaves, but guns were also very popular. Africans who got their hands on them first attacked neighboring tribes in order to capture and sell yet more slaves. Chiefs policed their turf just as drug gangs do today, executing rivals.

The first shipments to Spanish territory in the New World came directly from Spain in 1510, and the first cargo directly from Africa arrived in 1518. Thus, slavery had been practiced in Latin America for a century before the first blacks arrived in Jamestown in 1619.

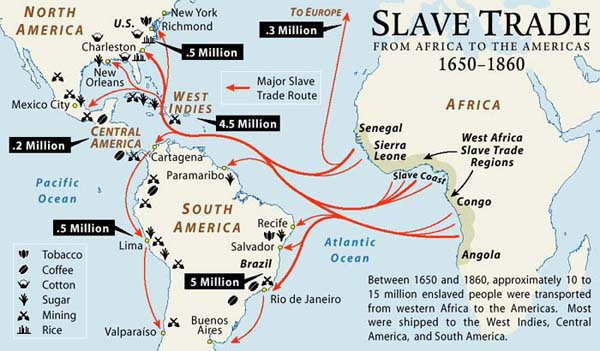

Most North American slaves came from West Africa, but Mr. Meredith notes that the port that shipped the largest number of slaves was Luanda in what is now Angola. The Portuguese controlled the area, and most of the 2.8 million slaves shipped from Luanda were bound for the Portuguese colony of Brazil, and for sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The next largest source of slaves was the coast of what is now Togo, Benin, and Nigeria–known then as the Slave Coast.

The mouths of rivers were the best trading posts. African chiefs sent their men up river in huge canoes with 50 paddlers and filled them with captives to sell to Europeans.

Part of the Atlantic trade stayed in Africa. The Akan people managed to keep control of the gold mines until the British seized them in the late 19th century. Slaves worked the mines, and the Akan bought slaves from the Luanda area when local supplies were low.

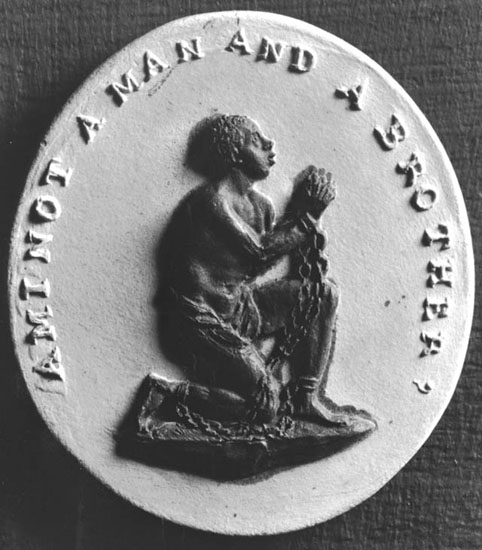

The end of the 18th century was the high water mark of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, with shipments reaching 80,000 a year. The British carried more than half of the trade, but Parliament, bowing to abolitionist pressure, passed a law in 1807 banning the slave trade in British ships. The British West Africa Squadron patrolled the area, and beginning in the 1840s, the navy began breaking up land-based slave operations as well. Africans were dumbfounded by this incomprehensible interference in age-old business practices.

An engraving produced by English anti-slavery campaigners in the 1700s. It reads “Am I Not A Man And A Brother?”

The British founded the colony of Sierra Leone initially as a place to send blacks who were not wanted in England, but later they used it as a haven for slaves freed by the navy. Between 1810 and 1864, some 150,000 blacks were settled there.

In the interior of Africa, however, the trade went on undisturbed. Tippu Tip was a Zanzibar trader who stripped a vast part of the Eastern Congo of ivory and slaves. A missionary who was appalled by the sight of one of his caravans in 1882 wrote that Tippu Tip’s men made slaves carry the ivory. Anyone who complained that the ivory was too heavy was speared to death and left in the jungle. This discouraged slackers.

Tippu Tip knew David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley, but could not understand what motivated explorers:

If you Wazungu [white men] are desirous of throwing away your life, there is no reason we Arabs should. We travel little by little to get ivory and slaves . . . . but you white men only look for rivers and lakes and mountains and you spend your lives for no reason, and to no purpose.

Of Livingstone he said, “He bought no ivory or slaves; yet he traveled further than any of us, and for what?”

Mr. Meredith reports that the best estimates for the total number of slaves shipped from Africa in the long-haul trade between 800 to 1900 come to about 24 million. They took the following routes:

Trans-Sahara: 7.2 million.

Across the Red Sea: 2.4 million.

From the East African coast: 2.9 million.

Trans-Atlantic: 11.3 million.

These numbers do not include the countless millions trafficked within Africa. Some 800,000 are estimated to have been brought to British North America.

Slavery, of course, continues in Africa. In 1981, Mauritania was the last country officially to abolish it, but did not provide for criminal penalties. Today Arabs there own an estimated 150,000 to 600,000 blacks, which means that as much as 20 percent of the population could be slaves. Slave status is hereditary, and slaves can be bought, sold, rented out, or given as gifts.

Historically, Arabs enslaved whites as well as blacks. Mr. Meredith describes the Janissary and Mamluk systems in which Christian boys were captured and trained as soldiers. He also describes the Barbary Pirate raids, estimating that at least one million Europeans were enslaved between 1530 and 1780. Christians were worked to death as galley slaves, and white slaves helped build 18th-century Algiers into one of the most beautiful cities in the world.

Religion and superstition

It is clear from The Fortunes of Africa that the continent has seen a great deal of religious frenzy, with as much jihad as in the Middle East. Islam’s sweep through all of North Africa in the 7th century is one of history’s prime examples of conversion by the sword.

Similar tactics spread Islam south of the Sahara. In the 18th century in what is now northern Nigeria, Usuman dan Fodio established the Sokoto caliphate, which forcibly extended Islam over an area of 180,000 square miles. In the 19th century a jihad movement of Tukolor tribesmen also spread Islam into great swathes of West Africa.

One of the most famous Muslim warriors was Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abdallah, better known as “the Mahdi.” He was a Sudanese hermit with a reputation for great piety. In 1881, he saw visions in which he learned that he had been sent to prepare for the judgment day. “We shall destroy this and create a new world,” was his motto, which he said came straight from Allah. It was his armies that attacked Khartoum in 1885, killing General Charles George “Chinese” Gordon.

The Mahdi died shortly after this victory, but his successor, Abdullahi, expanded his territory to the equivalent of half the size of Europe, and wrote a letter to Queen Victoria inviting her to come to his capital at Omdurman, submit to him, and accept Islam. Abdullahi ran his empire for another 13 years until Lord Kitchener led a heavily armed force into the Sudan from Egypt and destroyed the Mahdist army of “Fuzzy-Wuzzies” at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898.

In Somalia, the British had to fend off another Muslim fanatic they called the “Mad Mullah.” Muhammad Abdullah Hassan waged guerrilla war from 1900 to 1920, and eluded five military expeditions sent to kill him. “I wish to rule my own country and protect my own religion,” he explained. His poetry about the death of a British commander became a staple of Somali national literature.

The toughest native resistance to French colonization of Algeria was in the name of Islam.

A fanatical Muslim movement, known as the Sanusiyya, was started by Muhammad ibn Ali al-Sanusi in the 1880s and rampaged through Libya until 1931, when the Italians finally put it down using bombers and concentration camps. Mr. Meredith reminds us that Osama bin Laden spent six years building up Al Qaeda in Islamist Sudan. There has been nearly perpetual low-grade war between Christians and Muslims in northern Nigeria. Boko Haram is only the latest version of high-octane Islam.

Further south there have been even weirder enthusiasms. From 1856 to ’57 a cult grew up around the prophecies of a 16-year-old Xhosa girl named Nongqawuse, who persuaded her people that their ancestors would rise from the dead and drive the whites into the sea if the Xhosa slaughtered their cattle and destroyed their grain stocks. Forty thousand people died in the famine.

In German Tanganyika (today’s Tanzania), Kinjikitile Ngwale had visions that led him to believe that if his tribesmen used his holy water (maji) it would turn German bullets into water. In 1905 he started the Maji Maji Rebellion, in which some 26,000 men were cut down by German machine guns.

In the 1980s, a Ugandan spirit medium named Alice Lakwena started something called the Holy Spirit Movement to oppose the Ugandan government. She mixed up holy oil to smear on followers who believed it would stop bullets. She also blessed stones that were supposed explode like grenades. Her units went into battle singing hymns and marching in cross-shaped formations. This sort of thing worked better against Ugandans than against the Germans, so Miss Lakawena held out against the national army for several years.

Her relative, Joseph Kony, proclaimed himself a prophet in 1987, and press-ganged thousands of children to fight in his Lord’s Resistance Army. He told them his holy water made them immune to bullets. Mr. Kony got the support of neighboring Sudan against the Ugandan government, and his campaign of rape, mutilation, and murder displaced some two million people. He claimed that all he wanted was to start a new government based on the Ten Commandments, but in 2005, the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for his arrest. Mr. Kony is now thought to be holed up in eastern Congo.

The various civil wars in Liberia also produced colorful characters, such as General Butt Naked, who would sacrifice a child and then lead his men into battle naked. General Die and Captain Kill Easy also made lurid names for themselves in battles in which no one seemed to know what he was fighting for and everyone was high on drugs.

It is clear from The Fortunes of Africa that human life has not counted for very much on the continent. The colonial powers certainly did a great deal of killing, but they did it methodically and scientifically in the interests of empire. No one seems to rival black Africans for killing their own people. The 19th century Zulu king, Shaka, is notorious for arbitrary mass executions of entire villages, but there are less well known monsters.

The rulers of the kingdom of Buganda, in what is now Uganda, had unlimited power of life and death. In hard times, they practiced what was known as kiwendo, or mass killing of subjects to propitiate the gods.

When Mutesa took the throne, he had to kill about 30 half brothers to consolidate his position because he was the son of his father’s 10th wife. The British explorer John Speke recorded a meeting with Mutesa, in which Speke gave the king a gift of firearms, and demonstrated their usefulness by shooting a few cows. Mutesa immediately had the weapons tried out on some of his subjects, of whom he made a practice of killing several every day. In old age, Mutesa suffered from advanced venereal disease and resorted to extravagant kiwendo cures, sometimes sacrificing as many as 2,000 people in a single day.

A later Buganda ruler named Mwanga had a predilection for young boys. In 1886, when several pages refused his advances, he decided that Christians were the problem. He had 45 of them castrated, and then hacked or burned to death.

This sort of thing survived into the post-colonial era. Nowhere has shooting political rivals been more popular, and many “big men” have been mass murders. The number of victims of Idi Amin, who ruled Uganda from 1971 to 1979 is said to be half a million, and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe is still adding to his death toll. Mengistu Haile Mariam, who was president of Ethiopia from 1987 to 1991, had thousands of enemies killed, and kept famine relief out of restive areas, causing an estimated 1.5 million deaths.

There have been plenty of autocrats who were not mass murderers. Hastings Banda, who led Malawi to independence used to say, “Anything I say is law. Literally law.” Habib Bourguiba, the first leader of independent Tunisia, was once asked about the political system of his country. “System?” he asked. “What system? I am the system.”

Equatorial Guinea is a small country with lots of oil, and a per capita GNP of $35,000, which makes it easily the richest in Africa. However, all the oil wealth goes into the pockets of the ruling clique, so three quarters of the population live on about one dollar a day.

Many African countries do not bother with elections, and those that do are usually just putting on a show. Mr. Meredith notes that between 1960 and 1989, over the course of the 150 elections held in 29 countries, opposition parties were not allowed to win a single seat. Recently, opposition parties have actually won power in a few cases, but Mr. Meredith notes this usually means only that a different gang gets to loot the country.

At least this is government of some kind. Eastern Congo and most of Somalia have been a lawless mess for decades.

Botswana, just north of South Africa, seems to be a shining exception to the African rule of mismanagement and kleptocracy. It has a genuine democracy, a middle class, and enjoys economic growth–but it has advantages: Almost the entire population is Tswana, meaning there is no ethnic conflict, tribal governance was traditionally based on discussion rather than murder, and it has a thriving diamond industry. It does, however, have one of the highest AIDS rates in the world.

Mr. Meredith does not predict a happy ending. He writes that world food production rose by about 150 percent from 1970 to 2000, but in Africa it fell by 10 percent. From 1950 to 2010, the continent’s population more than quadrupled, from 225 million to 1 billion. Young people are swarming into reeking, pollution-choked cities surrounded by endless slums. The last words of the book warn that “the urban crisis . . . posed a threat not only to the stability of Africa’s cities but to entire nations.”

Africa poses threats beyond its borders. Africans who have wrecked their own countries are streaming into Europe, whose leaders do not have the backbone to keep them out. An exploding African population just to the south of a shrinking Europe is one of history’s great dysgenic menaces.

Population pressures and migration alone will keep Africa in the headlines. Along with The Fate of Africa, The Fortunes of Africa is an excellent history of what led to the current crisis.