Austerity Can’t Save White America

Hubert Collins and Chris Roberts, American Renaissance, November 21, 2020

As America becomes less white, it will be harder for conservatives to win national elections. But race is not the only factor. Even when the country was 90 percent white, Republicans still lost presidential races. In fact, in most of America’s landslides, the Republican lost. Since the 1930s, the losers of landslide elections have all had one thing in common: They promoted economic austerity, promising to cut social programs and/or raise taxes to shrink the national deficit and keep government out of the economy.

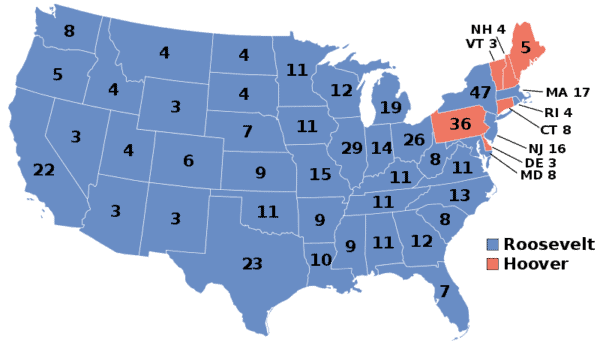

1932: Franklin Delano Roosevelt vs. Herbert Hoover

Popular vote: 57.4 percent for FDR; 39.7 percent for Herbert Hoover; 2.23 percent for Norman Thomas (Socialist).

Historian William E. Leuchtenburg writes that although FDR wasn’t always very specific about his plans for government largesse, he still:

“. . . hinted at the shape of the New Deal to come. FDR told Americans that only by working together could the nation overcome the economic crisis, a sharp contrast to Hoover’s paeans to American individualism in the face of the depression. In a speech in San Francisco, FDR outlined the expansive role that the federal government should play in resuscitating the economy, in easing the burden of the suffering, and in insuring that all Americans had an opportunity to lead successful and rewarding lives.”

Even Ayn Rand voted for FDR that year.

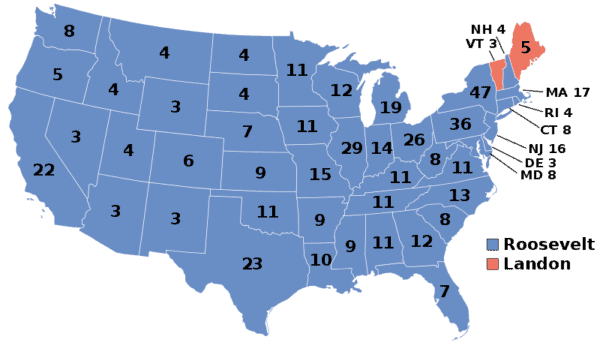

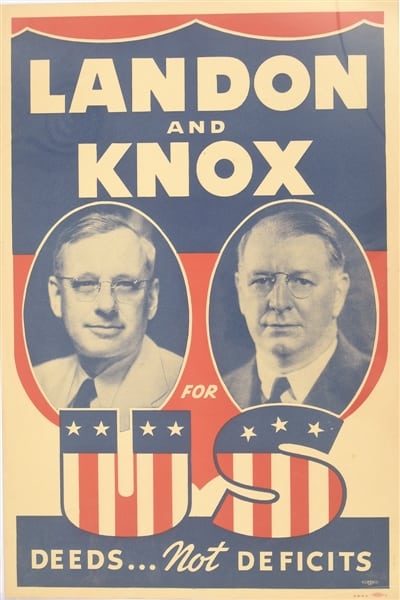

1936: Franklin Delano Roosevelt vs. Alf Landon

Popular vote: 60.8 percent for FDR; 36.5 percent for Alf Landon; 1.95 percent for William Lemke (Union).

Alf Landon, the loser, campaigned against FDR with the slogans, “Defeat the New Deal and Its Reckless Spending” and “Deeds Not Deficits,” and called the newly established Social Security system “unjust, unworkable, stupidly drafted, and wastefully financed.”

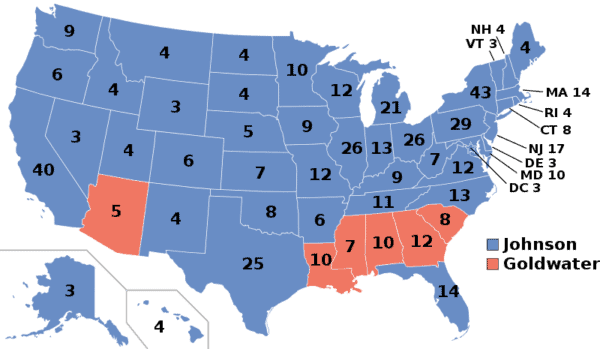

1964: Lyndon Baines Johnson vs. Barry Goldwater

Popular vote: 61.1 percent for LBJ; 38.5 percent for Barry Goldwater.

Barry Goldwater broke from the peace the Republican Party had made with the New Deal. He proposed deep cuts to all social spending, suggested Social Security should be voluntary, and recommended that the Tennessee Valley Authority be sold to the private sector. He said the Eisenhower Administration, the only Republican presidency of the previous 30 years, was “a dime store New Deal.”

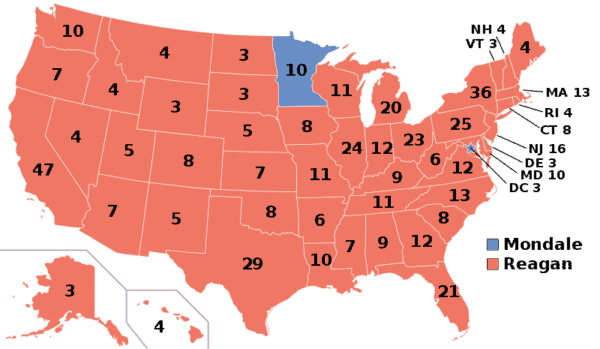

1984: Ronald Reagan vs. Walter Mondale

Popular vote: 58.8 percent for Ronald Reagan; 40.6 percent for Walter Mondale.

Walter Mondale is remembered as a bleeding-heart liberal today, but in 1984, he combined his dovish foreign policy and liberal social values with right-wing criticism of the President. Senator Mondale made the growing deficit a major issue. The mild-mannered Minnesotan’s DNC acceptance speech sounds like something Grover Norquist might write:

“Here is the truth about the future: We are living on borrowed money and borrowed time. These deficits hike interest rates, clobber exports, stunt investment, kill jobs, undermine growth, cheat our kids and shrink our future. Whoever is inaugurated in January, the American people will have to pay Mr. Reagan’s bills. The budget will be squeezed. Taxes will go up. And anyone who says they won’t is not telling the truth. I mean business. By the end of my first term, I will cut the deficit by two-thirds. Let’s tell the truth: Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I. He won’t tell you. I just did.”

The liberal political scientists Thomas Ferguson and Joel Rogers noted:

“On economic issues the Democrats offered voters almost nothing in 1984. Walter Mondale became the first Democratic nominee in many years to fail even to put forward a major jobs program. Nor did he couple his call for tax increases with a program of economic revitalization. There is no particular mystery as to why voters, faced with a choice between someone who promised them little besides a rise in taxes and a candidate who at least verbally championed economic growth and lower taxes, deserted Mondale for Reagan or declined to vote at all.”

The 1980 election is sometimes called a landslide, but it wasn’t. The results of the electoral college make it look like one, with Governor Reagan winning 44 states, but his share of the popular vote, 50.7 percent, was not exceptional.

Even in the 19th century, conservative presidential candidates who called for austerity rarely won elections. Andrew Jackson was America’s first populist, but his belief in small government has been mischaracterized. Although he did pay off the country’s debt and end the national bank, he was not a believer in “fiscal conservatism.” Before the Civil War, one of the biggest political debates was over how much federal money (raised almost entirely with tariffs) should go to “internal improvements” — building roads, canals, etc. Most of Jackson’s rivals, such as John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, believed the more improvements, the better. But Old Hickory did not, as is sometimes claimed, oppose them outright. Instead, he wanted them administered cautiously to avoid corruption. As he put it at the end of his sixth annual message as President:

“I am not hostile to internal improvements, and wish to see them extended to every part of the country. But I am fully persuaded, if they are not commenced in a proper manner, confined to proper objects, and conducted under an authority generally conceded to be rightful, that a successful prosecution of them can not be reasonably expected. The attempt will meet with resistance where it might otherwise receive support, and instead of strengthening the bonds of our Confederacy it will only multiply and aggravate the causes of disunion.”

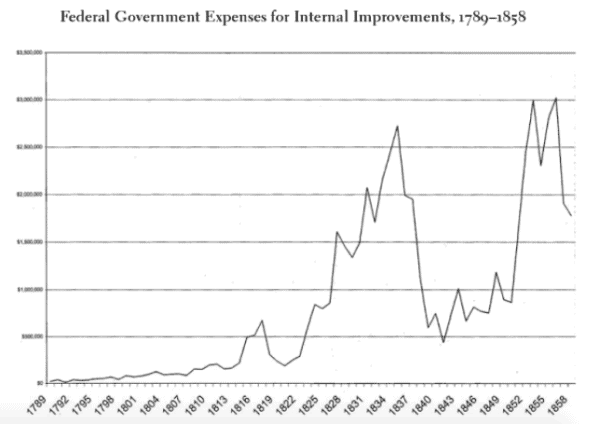

And indeed, President Jackson oversaw a great increase in spending on internal improvements:

Graph from page 362 of Daniel Walker Howe’s What Hath God Wrought; Andrew Jackson was president from 1829-1837.

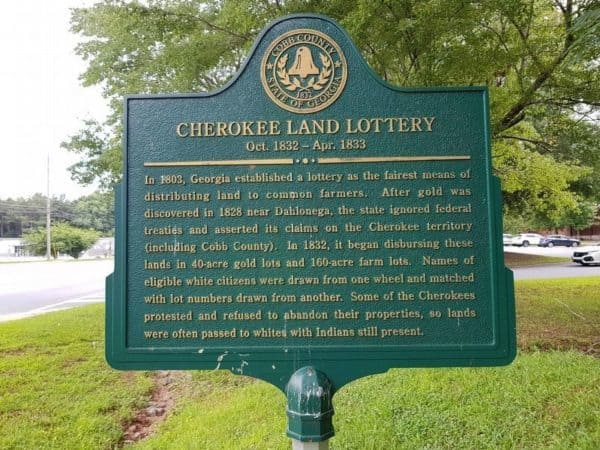

Jackson’s Indian Removal was a populist economic policy. White expansion made new land available to Americans unable to afford any in areas that were already settled. As Georgian yeomen used to sing:

“All I ask in this creation

Is a pretty little wife and a big plantation

Way up yonder in the Cherokee Nation.”

New frontiers gave poor people a chance to stake their own claims on farmlands. Even when the government made the new territory its own, the land was quickly parceled and either sold off cheaply or granted by lottery. Opposition to these policies came from that era’s “woke” elite — Religious New-Englanders whose economic wellbeing was tied to cities and ports, not to land or farms.

Credit Image: J. Makali Bruton / The Historical Marker Database

In the second half of the 19th century, many Democrats took the populist stance of eliminating the gold standard to increase inflation in order to reduce the debts of farmers. The Republican Party said that was economically unsound, but had its own populist proposal: higher tariffs to protect American industry and American workers. Neither was the “austerity” party; each was trying to protect its constituencies.

Today, the Republican Party represents austerity. As David Frum lamented in 2011:

“In the throes of the worst economic crisis since the Depression, Republican politicians demand massive budget cuts and shrug off the concerns of the unemployed. In the face of evidence of dwindling upward mobility and long-stagnating middle-class wages, my party’s economic ideas sometimes seem to have shrunk to just one: more tax cuts for the very highest earners.”

There are many examples of the GOP putting “small government” policy über alles. In 2016, Donald Trump broke with that. His campaign manager, Steve Bannon, a self-described “economic nationalist,” wanted “a trillion-dollar infrastructure plan,” along with regulatory relief for businesses and higher taxes on the rich to pay for tax cuts for the middle class. Two of Mr. Trump’s main campaign issues were limiting free trade to protect American manufacturing and scaling back immigration to protect American wages. But once he was in office, he passed a tax cut that might as well have been written by Mitt Romney or John Boehner:

Under #TaxCutsandJobsAct a married couple earning $100,000 per year ($60,000 from wages, $25,000 from their non-corporate business, and $15,000 in business income) will receive a tax cut of $2,603.50, a reduction of nearly 24 percent.

— Senator John Cornyn (@JohnCornyn) December 19, 2017

These policies do not benefit the middle class that is the bedrock of GOP support — and the rich people who do benefit don’t even vote Republican in high numbers. President Trump could have cruised to reelection if he had given unemployed whites across the Rust Belt “government works” jobs building roads, schools, bridges, dams, etc. In 2016, he gave voters the impression that he would do that, but he governed very differently. His 2020 campaign didn’t even include many of his main 2016 themes.

Trump 2016 would always bring up jobs, outsourcing and war. Now there’s none of that. He just whines like a fox news grandpa. #Debates2020 #Debate2020

— Secular Talk (@KyleKulinski) October 23, 2020

Am I having a stroke pic.twitter.com/OuRH2DtRYi

— american nationalist (@NationalistTV) July 26, 2020

How to Win

Any Republican with economic proposals to boost the middle- and working-classes, as against the Democrats’ “top-bottom” alliance of liberal elite and troublesome underclass stands to win national elections. This candidate wouldn’t have to rely on finicky “suburban moms” giving him narrow victories in “purple states.” Instead, he could challenge Democrat dominance in the Midwest and New England while holding onto the “red states” of the 2000s.

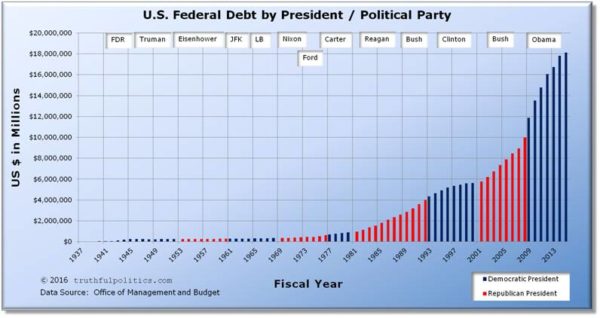

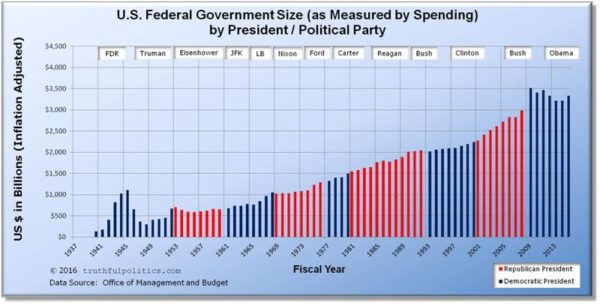

Successful right-wing presidential campaigns have three themes: National greatness (especially on the world stage), a return to order, and opposition to vice and/or leftist degeneracy. George W. Bush defended Christian values and denounced Islamic terrorism. Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush defended Middle America from the crime and the radicalism of the 1960s and fought Communism. Some cut taxes and overregulation, but laissez-faire economics was not their top issue. President Nixon created the National Cancer Institute, the Council on Environmental Quality, and the Environmental Protection Agency — and wanted “big government” to expand medical coverage. Before him, President Teddy Roosevelt broke up business monopolies and supported the beginnings of a welfare state. And for all their promises, the government and its debt grow even when Republicans are in office:

Few Republicans really believe in small government. As political scientist George Hawley has shown in White Voters in 21st Century America and The Vanishing Tradition, there are very few Republican voters who agree across the board with mainstream conservative media, such as The Daily Wire or National Review. Even within the Tea Party, only a minority opposed all of these: gay marriage, abortion, marijuana legalization, even minimal economic intervention, and an aggressive foreign policy. Other analysts and plenty of polls show the same thing:

Fox News Exit Poll

Change to a government-run health care plan

Favor 72%

Oppose 29% pic.twitter.com/9220tD7lms— Political Polls (@PpollingNumbers) November 3, 2020

Demographic change puts conservatism at a permanent disadvantage. But the GOP does itself no favors by opposing any government expenditure other than defense. Majorities of white Americans join the Right when they are threatened by violence and radicalism at home or abroad. The threats sometimes change: in the 1960s, Middle America’s enemies were hippies and Communists; today the threats are “social justice warriors” and Jihadists. Other threats are more constant, such as immigration and violent crime. But America never turns to economic austerity to solve problems. White Americans deserve politicians who care about their cultural values and their economic interests. Until the Republican Party starts protecting both, it will keep circling the drain.