The Truth in Black and White

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, September 7, 2020

An American Dilemma, written by the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal, may have been the most influential study of American race relations ever written. Published in 1944, this 1,400-page book went through 25 printings — an astonishing number for a heavily academic work — before it went into a second, “twentieth anniversary” edition in 1962.

The dilemma arose out of the attempt, beginning in 1619, by whites and blacks to live together in what became the United States. The country stumbled through several systems of racial organization, all now universally reviled: slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation. Our current system began with the civil rights revolution of the 1960s. After 350 years of hierarchy — often written into law — the United States officially embraced equality. Racial discrimination in hiring and accommodation was forbidden by law, and the nation started an immense moral campaign to eliminate race as a relevant criterion for any purpose. Our country was to become one in which race did not matter.

It was a time of great optimism. In a postscript to the “twentieth anniversary” edition of The American Dilemma, Arnold Rose of the University of Minnesota wrote that improvements in race relations “between 1940 and 1962 appear to be among the most rapid and dramatic in world history.” Rose added that at this rate, racial prejudice “will be on the minor order of Catholic-Protestant prejudice within three decades.” (xliv) Three decades would have taken Rose to 1992, and since then almost three more decades have gone by. Rose was wrong.

We live in the era of Trayvon Martin, white privilege, Black Lives Matter, Oscars so white, race riots in Ferguson and Baltimore, and even claims that the President of the United States is a white supremacist. Fifty-eight years after Rose wrote those words, are we not justified in asking if black-white differences will ever be no worse than those between Protestants and Catholics? For how long will race continue to be the American dilemma? For another 60 years? Forever? Many people think it is immoral even to ask such questions, because they suggest that it may be impossible to build a society in which race doesn’t matter.

If anything, race seems to matter more and more. It has been so hard to build a society in which it doesn’t matter that some people now insist on a different but deeply confusing goal. The fashionable view today is that trying to ignore race is “colorblind racism,” which “erases” the richness of racial identity. But racial identity itself has racial distinctions: “Persons of color” are allowed and even encouraged to think of themselves as proud members of their race, but for whites, racial identity is shameful. Whites may speak as whites only to apologize.

But are well-intentioned whites really slighting non-whites if they try to treat them exactly as they would other whites? The only way for whites to affirm the racial identities of non-whites is to treat them differently from whites. But wasn’t different treatment for different races the problem to begin with? Or are whites to overcome racism by treating non-whites better than they treat whites? That was certainly never part of the civil-rights bargain of the 1960s.

This is as bewildering and annoying to whites as the idea that they are all racist, no matter what they think or do, but that “persons of color” can never be racist, not matter what they think or do. This is another classification by race; why isn’t it “racist”?

Clearly, we are to believe that the race problem is exclusively a white problem. White people were at fault from the start, and only they can solve the problem. But this puts an impossible burden on ordinary whites. They had no part in building American society and their best efforts to treat all people equally apparently aren’t good enough.

This book doesn’t try to solve these riddles; they are merely examples of the surprising turns the “dilemma” has taken, and of complexities that Gunnar Myrdal and Arnold Rose could never have imagined. What this book does is paint an honest picture of black-white relations that may make it easier to understand why conventional thinking leads us into logical traps. Conventional thinking is wrong; that’s why it will never solve the dilemma.

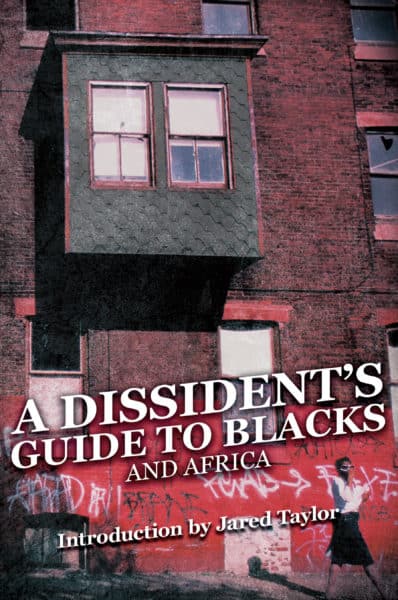

This book is free from dogma, preconceptions, and wishful thinking, and this freedom explains why the word “dissident” is in the title. The authors of this anthology are dissidents, just as Andrei Sakharov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and Yuri Orlov were dissidents in the Soviet Union. We are so badly out of step with orthodoxy that we risk our reputations and livelihoods when we write what we believe — and even know — is true. We are not yet likely to be expelled from the country or put into mental institutions, but penalties for dissent are high. This is why race is surely the subject Americans fear the most and about which they are the most dishonest.

One of the great strengths of this book is its variety. Some of the authors have studied and written about race for decades. Others have simply written about something they saw or experienced. Some of the authors are black. Some live in Africa. This variety of tone, approach, author, and focus made it so difficult to group the chapters thematically that they are presented in no particular order at all. Every chapter is an article that first appeared in American Renaissance, and each begins with the date it appeared in either the monthly magazine or on the website.

This book does not ask specific questions, nor does it draw specific conclusions. But I believe that, taken together, these essays suggest profoundly important questions and imply conclusions that are just as important. They are questions America and the world cannot afford to ignore, and conclusions that America and the world will be able to draw only after a thorough reappraisal of virtually everything it is now fashionable to say about race. Race is not a “social construct.” The races are not equivalent and interchangeable. Diversity is not a strength. Only after we understand these things can we begin to think realistically about how to solve the American dilemma.