From Public Policy to Public Quackery

Joseph Kay, American Renaissance, June 13, 2020

Current discussions on race have an almost surrealistic quality. How many people can correctly identify Confederate General Williams Carter Wickham, whose statute was recently pulled down from its pedestal in Monroe Park, Richmond, Virginia? Does anyone seriously believe that banishing it will do anything useful? Will changing our vocabulary — for example, redefining “criminals” as “those involved in the criminal justice system” — reduce crime or help criminals lead a decent life? Future clear-eyed historians might write about “The Age of Hysteria: Race Relations in the Early 21st Century.”

Understanding such craziness involves recognizing that humans naturally find solace by seeking control over their lives. This may be superstitious (sacrificing a chicken to win the lottery) or even self-destructive (taking arsenic to cure syphilis) but the act of “doing something” is almost always more attractive than doing nothing. Indeed, “doing something” is a staple in the self-help industry, where the troubled are advised to take charge of their fate.

For the seriously ill, “doing something” may follow a progression from the sensible to the bizarre, as initial actions fail to cure; desperation replaces rationality. A person diagnosed with cancer may start by heeding his doctor: taking medicine, eating better, joining a support group and so on — all with a clear connection to a desired outcome.

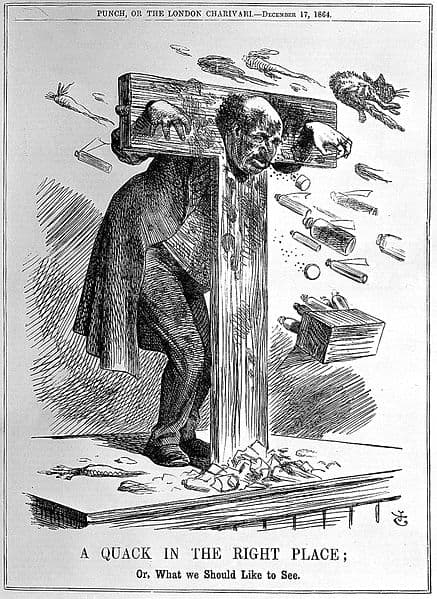

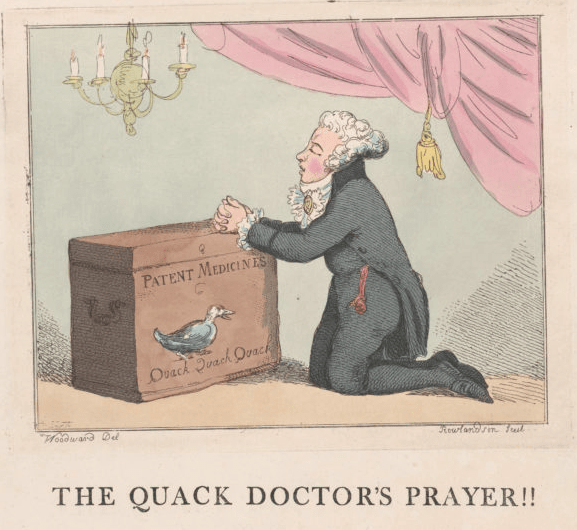

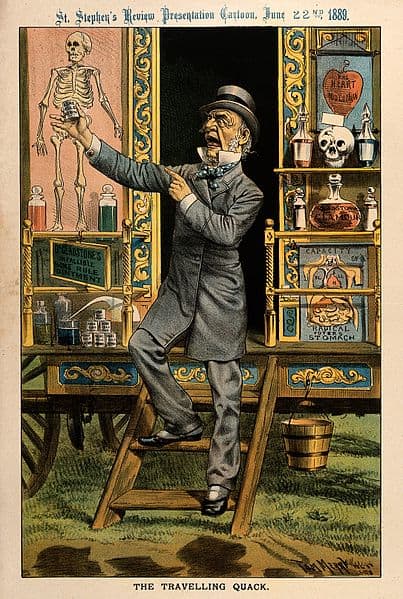

If matters deteriorate, “doing something” can drive a patient into the merely reassuring and even dangerous. This is the world of quackery, of snake oil and faith-healers hawking miracle cures “the government doesn’t want you to know about.” One website about alternative cancer treatments lists several dozen bogus cures, and the desperate are all too happy to believe reassuring testimonials.

There is a parallel with public policy: The repeated failures of ameliorative policies bring exasperation, and the exasperated turn to snake oil. The crusade to achieve racial equality clearly illustrates this progression from rationality to quackery. When the quest began in the 1960s, widespread optimism was reflected in a popular expression, “The Moon and the Ghetto.” If we can send a man to the moon, we can fix inner cities.

Early legislation was based on an arguably logical connection between problems and solutions. Federally funded jobs programs would uplift young blacks so they could participate in a modern economy. The 1964 Civil Rights Act banned discrimination in public accommodations and hiring. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 would overcome decades of black disenfranchisement while vigorously enforcing anti-discrimination laws. Head Start would help overcome the disadvantages of growing up poor and thus, eventually, lead to equal outcomes. Washington would make all federal contractors practice affirmative action to compensate for past injustices.

President Lyndon Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act, July 2, 1964.

Through the 1970s onward, there was a flood of new civil rights legislation. Alas, all the laws and spending failed to produce results, and in most cases there was deterioration. Current rioting illustrates that a large, unruly black underclass still exists, just as it did during the 1960s and 1970s. Charles Murray’s Losing Ground, published in 1984, showed the failure of billion-dollar uplift programs, and is still relevant. Black academic achievement has remained flat; “minority” college admissions, especially at top schools, would collapse if not for affirmative action, and even privately funded voucher programs have barely altered the record of underperformance. Millions spent on public housing have changed the appearances of slums but not improved the inhabitants. Key measures of pathology — illegitimacy, drug addiction, and crime — remain high. Yes, there is now a new black middle class, but how much of it depends on government jobs and political pressure? Are all those deanships of Diversity and Inclusion anything more than cosmetic positions created to placate black activists?

Sustained failure prompts the urge to “do something,” even if purely theatrical, pointless, foolish, or cynically dishonest. Consider today’s penchant for blaming the plight of blacks on “institutional racism,” or “structural racism,” or “systemic racism,” and other invisible forces. This is the equivalent of attributing a drought to angry gods. I have yet to see a single scientific study that even goes through the motions of trying to quantify or verify these malign influences. Do whites radiate racism as they might radiate heat or odor? How, exactly, does this radiation debilitate blacks; and, as with all toxic radiation, can it be blocked, or does a cure require the infected white person to be disinfected via contrition? Of course, to demand scientific proof is racism.

What is achieved by apologizing for the supposed sins of dead white men? Will acknowledging white responsibility for the evils of slavery contribute to black home ownership, reduce black criminal behavior, or improve black school performance? Such collective apologies are like rituals of religious devotion, in which the supplicant begs God for mercy and promises to lead a new and more righteous life. Walmart has just pledged $100 million to fight “systemic racism,” but does anybody believe this pledge is anything more than a self-promoting gesture? In my own upscale, almost entirely white enclave, a recent notice on a community e-bulletin board asked the members to set up a local “End White Supremacy” group. One can only image how this group will cool racial tensions in America.

There is a renewed frenzy to erase all memory of the Confederacy, from banning the battle flag to removing statutes, and even digging up buried generals and hiding the bodies. This relocation is a huge undertaking, involving thousands of sites from parks to cemeteries, but it is only the latest in a long series of purges. Beginning in Chicago in 1968, the renaming of streets in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. progressed so far that by 2014, by one estimate, there were more than 900 such streets in 42 states. The latest application of this cosmetic therapy is that the open space outside the White House is now “Black Lives Matter Plaza.”

The intersection of Martin Luther King, Jr. Ave. and Malcolm X Ave. in Washington DC’s black ghetto. (Credit Image: Chris Roberts / American Renaissance)

Let’s not forget that removing slave-owners’ names from public schools, also a task of major proportions, is far from complete (“Robert E. Lee” alone adorns 80 schools and “George Washington” countless more). Academics have been busy for years issuing anti-racism proclamations. In 2001, for example, the American Psychological Association declared that it “denounces racism in all its forms for its negative psychological, social, educational and economic effects on human development throughout the life span . . . .” Has anyone figured out exactly how this proclamation improved the lives of blacks?

The battle hardly ends here. Cities now declare racism to be a public health menace as if it were cholera. The science of public health began over a century ago; why has it has taken so long to discover this new and dangerous pathogen? Nevertheless, the American Public Health Association has announced that “Racism is a driving force of the social determinants of health (like housing, education and employment) and is a barrier to health equity.” And for good measure, to anticipate today’s rioting, in 2018 it found that police violence is also a public health issue. Will NIH will commit millions to find a cure, or better yet, a vaccine for racism or police violence?

This quackery has flourished for decades, and follows three patterns. The first is its democratization; the costs of quackery have fallen as the opportunities for pontification expand. Ocean cruising, once the exclusive domain of the rich, is a useful parallel; today a mass-market business lets ordinary people travel in luxury. When formulating race-related uplift measures in the 1960s, it took some pretense of evidence-based arguments linking policy and outcomes to enter the marketplace of ideas, and policy making was a relatively exclusive club.

Today everybody can play the “do something” game while acquiring valuable virtue-signaling points. Hollywood seems to think it can improve the skills of black filmmakers by giving them Oscars, and TV commercials now feature Ozzie-and-Harriet-style black families as if this will reverse high rates of illegitimacy. Suggesting foolish solutions is a cheap way to fill airtime on TV cable news.

At a recent event at Sag Harbor, Long Island, the upscale inhabitants cheered as 100 local surfers staged a “National Paddle Out” to honor the memory of George Floyd. No doubt, these wealthy bystanders were “doing good” in their own minds, and with the inevitable escalation of these status-boosting contests, the next craze will surely be lavish A-list cocktail parties to honor looters (recall Leonard Bernstein’s Park Avenue soiree to celebrate the Black Panthers, so aptly depicted by Tom Wolfe).

A second pattern is the absolute incoherence of the quackery. This is not Marxism or any other intellectually systematic program. Rather, it is a collection of semi-literate slogans and rioter chants that evaporate under scrutiny. What does “Black Lives Matter” or “Fight White Supremacy” actually mean? Amorphousness precludes rebuttal. At least communism had a clear manifesto. The Great Society may have failed, but it least it offered a vision of government’s role in economic progress. Today’s incoherence only empowers muddle-brained hotheads.

Finally, a more serious pattern is that as participants try to outdo each other in status-bestowing quackery, the remedies grow more dangerous and divorced from reality. Virtue-signaling is a series of ever-shorter dopamine highs. Parallels from cancer treatment again offer insight, and one particularly dangerous quack treatment is Chelation therapy. This “cure” supposedly extracts harmful metals from the body with doses of chelating agents. Although chelation therapy can be used to treat heavy-metal poisoning, it is worthless against cancer; and, as the American Cancer Society has warned, it can lead to toxic reactions, kidney damage, irregular heartbeat, and even death.

Ending mass incarceration, eliminating cash bail, and defunding police departments (including removing pro-police shows from TV) are obvious parallels to Chelation therapy. That such policies will most likely harm blacks — especially ghetto blacks — hardly matters to those desperate to “do something.” And why should it? To claim that the cure is worse than the disease is not just an unwillingness to “do something;” it’s “racism.”

Two questions remain: (1) how long can this hysteria last, and (2) what explains it?

First, it could go on for decades. Its very formlessness and irrationality make it invulnerable. This is not like mortal illnesses, in which death ends the search for miracles. There is no trusted authority to halt the madness, and the hucksters who once peddled Ebonics, who then moved on to implicit bias training, who then demanded reparations, now insist that schools be re-named after George Floyd.

Money undoubtedly explains this persistence, especially in education and law-enforcement. Here the quacks are entrenched, and usually supported by the establishment. Defunding the police will unleash more violence — and more quacking about how we must “do something.”

The deeper explanation — one unspeakable in public — is that each new quack remedy pushes awkward questions about racial differences off the table. As long as there is a newly discovered mysterious miasma of white domination or a new magic bullet to overcome some racial gap, why consider the genetic contribution to intelligence or crime rates? Nor is there any need to admit that some race-related problems can’t be solved. To the extent that quack solutions are never put to serious analysis, and there is an endless supply of both problems and snake oil, racial environmentalism sails along unquestioned.

Quackery is popular because it makes us feel good and avoids troubling realities. Who dares argue with that?