Affirmative-Action Portraits

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, February 13, 2018

When the collapse begins, people generally don’t realize it. Rarely do statesmen acknowledge the Golden Age of their nation has passed; every leader tells his people their best days lie ahead. And the rituals of statecraft, above all, are designed to impose a sense of continuity and eternity. The nation is forever, the state is uncontested, and the polity is essentially the same as it was when it was founded. Even a revolutionary regime tries to co-opt the legitimacy of its predecessors, not confess to the masses that it is composed of mediocrities and frauds. Decline is usually subtle.

Except when it’s not. Like when the official paintings of Barack and Michelle Obama were unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery on Monday.

The President of the United States is the head of state as well as the head of government. The official portrait is a serious matter. Whatever we think of a president or his policies, he represents the nation. Thus, the official representation of a president is in some sense a representation of the nation.

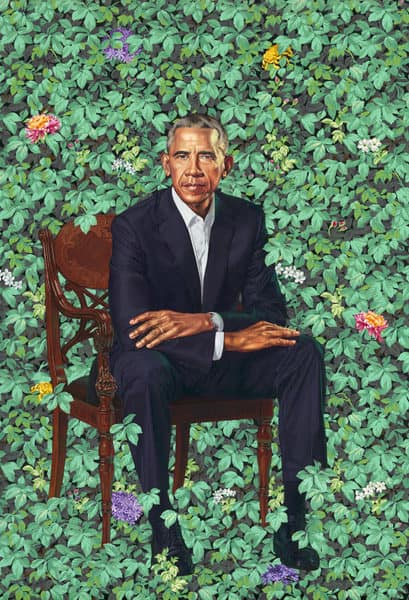

President Obama chose as the artist for his portrait one Kehinde Wiley, a diversity twofer who is both black and gay. Mr. Wiley’s prints, all of which feature non-whites, portray blacks framed in kaleidoscopic backgrounds of flowers. This means Mr. Wiley does not have to grapple with perspective, and it gives each paining a cheap look, like an airbrushed drawing you can get on a t-shirt. He may not even do any of the actual work, as he seems to simply do the self-promoting while outsourcing the actual painting to the Chinese.

As lovingly chronicled in the Washington Post, Mr. Wiley thinks that blacks are portrayed too negatively in the media, and that this leads to horrors such as the death of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. His art is meant to correct “this charade, this two-dimensional caricature” of blacks.

Mr. Wiley’s artistic viewpoint is best described as resentful plagiarism, which contradicts his stated purpose of avoiding caricature. His characteristic technique is to substitute blacks into great works, such as Jacques-Louis David’s “Napoleon Crossing The Alps.” “If Black Lives Matter, they deserve to be in paintings,” Mr. Wiley claims.

The result is not an homage to classic works, nor even parody. It is affirmative action applied to painting, something below even being derivative. Blacks are inserted into other paintings out of a feeling of entitlement. Because the paintings seem cheap and uninspiring, they serve only to insult the original.

Equestrian Portrait of King Philip II, 2009 Kehinde Wiley. (Credit Image: © Serge HasenböHler/Avalon via ZUMA Press)

Mr. Wiley explained his rationale for substituting blacks into these works:

Most of the work that we see in the great museums throughout the world are populated with people who don’t happen to look like me. As a child, I grew up studying and worshiping those great works of Western European painting. But I also wanted to fulfill the goal of feeling a certain personal presence in that work.

This man is at least capable of recognizing greatness. Making unattractive knockoffs of classic works as an appeal for inclusion or recognition should make us feel sorrow. It is another way of saying that Africa does not have its own tradition of painting worth studying and exploring. But rather than producing something authentic, Mr. Wiley gives us glorified Photoshops that portray a rapper as if he were Napoleon Bonaparte.

“The whole conversation of my work has to do with power and who has it,” says Mr. Wiley. But his work is not an expression of power. It’s a plea for a handout or for recognition. One hates to psycho-analyze, but President Obama has noted that both Mr. Wiley and himself were emotionally scarred by being abandoned by African fathers and raised by American mothers.

There is a more disturbing element in Mr. Wiley’s work. Some of his versions of classic paintings, such as Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Judith Slaying Holofernes,” depict black women holding the decapitated heads of white women. Mr. Wiley describes this lightly as a “sort of a play on the whole ‘kill whitey’ thing.” It certainly fits the recent pattern of art crudely portraying the slaughter of whites at the hands of blacks. But this does make Barack Obama’s praise of Mr. Wiley paintings because of “the degree to which they challenged our ideas of power and privilege” even more disturbing. Mr. Wiley also challenges our view of human anatomy: For some reason he gave Barack Obama what looks like an extra pinky on his left hand.

Credit Image: © Npg/Notimex/Newscom via ZUMA Press

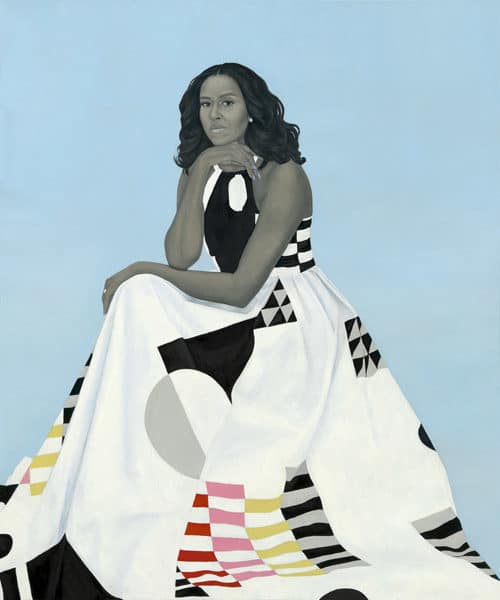

But this is still better than the portrait of Michelle Obama. It looks more like Jennifer Lopez than the former First Lady, and artist Amy Sherald has a distinctively Third World artistic style; her figures almost always stare straight out of the canvas. The propaganda during the Obama Administration about the “beautiful” and “stylish” Michelle Obama was overblown, especially in light of the media and fashion industry’s scorn for our current First Lady. But Miss Sherald’s depiction is far worse than what Mrs. Obama deserved, portraying her as homely and lifeless, like a child’s drawing of a person. But while a child’s drawing can be a source of pride, Amy Sherald is 44 years old.

Credit Image: © Npg/Notimex/Newscom via ZUMA Press

Like Mr. Wiley, Miss Sherald justifies her art as a means of getting black people into white people’s museums. As she put it in an interview with NPR: “As a black woman and somebody who paints Americans, that narrative of images of us just being were things I wanted to see exist, you know, within the museum institutions.” Being “within the museum institutions” appears to be more important than painting great work.

And lest presidential portraits simply be dismissed as a bureaucratic enterprise, some of the presidential portraits are indeed great art. Aaron Shikler’s portrait of John F. Kennedy will always hit the viewer emotionally. Rembrandt Peale’s sphinx-like portrayal of Jefferson captures the man who remains the most mysterious and complex of the Founding Fathers. President Teddy Roosevelt’s forceful portrait makes us feel like our former national leader is personally challenging us, urging us to take up the “strenuous life.” But even less effective portraits have dignity and respect, not just for the subject but for the viewer. When Barack and Michelle Obama unveiled their own portraits, they seemed taken aback rather than delighted.

The late Christopher Hitchens once said about North Korea that he had vowed to avoid invoking George Orwell’s 1984, but found he couldn’t help but make the comparison, so aptly did it fit. Similarly, one wants to avoid the old story about the boy and the Emperor’s new clothes, but the wild praise of the portraits from the likes of the New York Times makes it difficult. As Theodore Dalrymple said, “When people are forced to remain silent when they are being told the most obvious lies, or even worse when they are forced to repeat the lies themselves, they lose once and for all their sense of probity.” When an entire nation has to pretend representations of its former first couple are great works of art rather than two glorified participation trophies, the nation loses its self-respect.

Of course, it’s not just the National Portrait Gallery. Every day sees a once prestigious institution or award hollowed out by political correctness or the demand that we accept the mediocre as somehow elevated. Consider the state funeral given to a woman whose sole accomplishment was to sit down in a bus for a half hour. Or the urge to have Trombone Shorty play part of a “classical” music concert in the hope that a black audience will stick around for Beethoven. Or even the worshipful coverage of black “national debate champions” who “won” by refusing to accept the debate topic and instead loudly complained about racism.

There comes a point when an honor from a mainstream cultural institution becomes self-discrediting. We have an affirmative-action culture, in which “access” to institutions is prized over accomplishment, talent, or even meaning. America has become an affirmative-action nation. Future historians, looking through the portraits of American leaders, will be able to tell when the transformation from First to Third World took place.