Boycott by Whites Threatens South African Restaurants

Dan Roodt, American Renaissance, June 1, 2017

Spur Steak Ranches is a popular, pseudo-American chain of restaurants in South Africa. On March 19, at a restaurant in a shopping mall not far from Johannesburg, the child of a black patron apparently hit the child of a white patron. The white complained to the mother, which led to a heated confrontation, recorded on a cellphone video that went viral. It seems that the black woman first used the “F word” in English, after which the white man responded with a few choice expletives in Afrikaans. To apportion blame in such a situation would be difficult, but the video immediately added to black-white polarization.

Two days after the argument, Spur issued a media release, explaining that it would ban the white man from its chain of restaurants. Whites, especially Afrikaners, responded with an immediate call for a boycott. Sales at Spur outlets are reportedly down by 25 to 45 percent.

At first Spur, which is listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, ignored the boycott, but over the last week or so, CEO Pierre van Tonder began a major public relations drive. His angle: “The boycott is hurting independent franchisees” and leading to hardship and job losses for them.

One such franchisee, Alan Ranson, described the boycott to the left-wing 702 talk radio station:

It happened almost immediately . . . . It was like wildfire. Within a week we had immediate reaction, and then it just grew. And grew . . . . In 34 years I have never seen anything like it . . . . We are battling. We are suffering.

The print article by the radio station has the title “Spur is bleeding from right-wing boycotts.” Another left-wing site, The Daily Maverick, ran an article called “A taste for strife: How a right-wing boycott has lost Spur millions and counting.” In South Africa, the term “right-wing” is now virtually synonymous with “Nazi” or “white supremacist.” The mainstream media invariably use it when they write about whites, Afrikaners and the Afrikaans language, or any dissent from the current system of majoritarian black supremacy.

The CEO of Spur warmed to the “right-wing” theme in an open letter on the South African Huffington Post:

To understand why some franchisees in specific areas were more affected than others, we researched the demographic context and established a link to historically conservative political constituencies. This data also helped us to make sense of the racist comments on social media and political leanings of the groups driving the boycott. Journalists who investigated the incident and the racist responses and threats online characterised the boycott as a right-wing boycott.

The boycott is particularly successful in white, Afrikaans-speaking areas where people in the late 1980s supported the former Conservative Party in its vehement opposition to handing power over to the African National Congress (ANC.) However, there are other factors. One is the tendency of corporate South Africa to bend over backwards to accommodate both our crazy Afro-Marxist government and the anti-white black middle class that thrives on government jobs and affirmative action. Spur’s ban against its white customer was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The sentiment on social media among whites is decidedly against Spur.

The other element is “white flight.” Restaurants or bars that become “too black” lose white clientele. As an “affordable family restaurant,” Spur Steak Ranches have darkened considerably, and in many areas now probably make whites feel uncomfortable. One reason is the noise. For whites, SA blacks sound as if they are screaming when they are just having a normal conversation in their own African languages.

Then there is the matter of staff. After the collapse of Zimbabwe under Robert Mugabe, the Johannesburg restaurant sector was overrun by legal and illegal migrants. Zimbabwean waiters and cooks essentially keep their country afloat by sending part of their earnings to relatives back home. In my experience, they are never satisfied with their tips. Afrikaners also prefer being served in Afrikaans, a language at least understood by most local blacks. Zimbabweans consider Afrikaans an irritation, and sometimes make it arrogantly clear that they do not speak it. There have also been rumors of Spur waitresses dripping body fluids into the food they serve to whites.

So the black child hitting the white child may not have been the only thing that angered the white man in the video — who does seem to be overreacting.

The average Spur has a white franchise owner who, with or without a white manager, oversees a staff of about 30 blacks. Although it has been years since I went to a Spur, I was impressed neither by the food nor the service. Spur’s cowboys-and-Indians theme has an underlying anti-cowboy, pro-Indian flavor, which is part of the chain’s corporate political correctness.

Spur is now trying to create sympathy for the white franchisees, but the “right-wing” boycotters are not falling for it. I was at the Johannesburg airport the other day, and the Spur was virtually empty while the hamburger joint right next to it was full.

A happy outcome of the Spur boycott is that people are now looking for alternatives and discovering independent family-run restaurants — and are sharing this information on social media. A few days ago, my family and I were looking for a place to celebrate my 60th birthday. I Googled in Afrikaans, and found a new place in Pretoria that had been open only for two months — more or less since the Spur boycott started. We had to drive about 25 miles, but it was worth it.

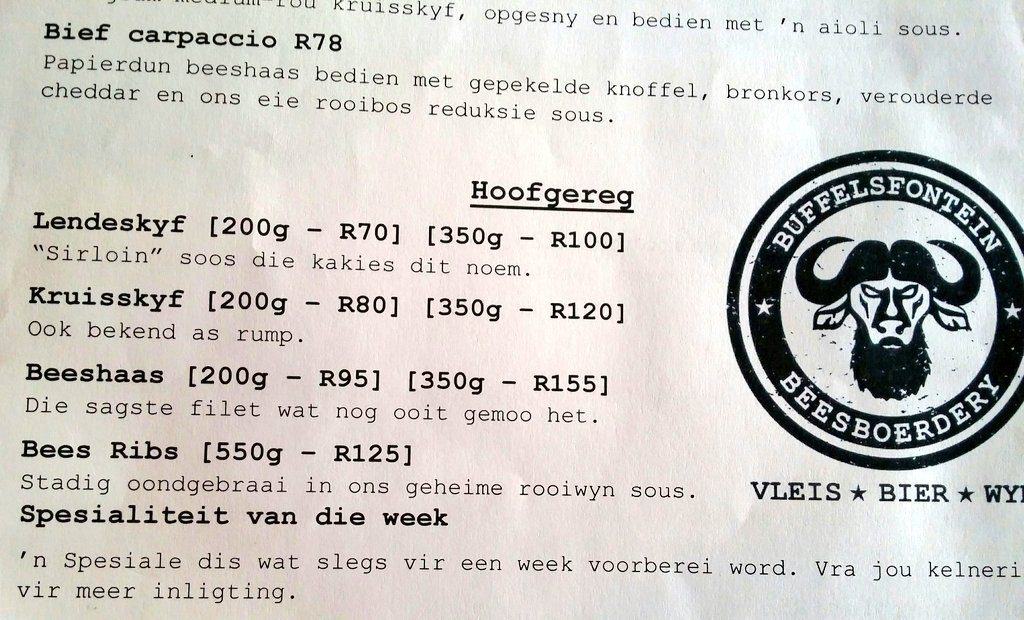

It was a hard-core Afrikaner steakhouse, called Buffelsfontein Beesboerdery, which literally means “Buffaloes Fountain Cattle Farming.” The African buffalo is a formidable animal, capable of killing people, so the name expresses a kind of Afrikaner machismo in a playful, ironic way. There was no English on the menu, except in a few places the words “sirloin” or “fillet” in quotes for the stray tourist.

The waitresses were young, blonde, beautiful, and courteous, with no Zimbabweans in sight. In fact, I saw no blacks at all, whether among the staff or patrons. The piped music was either Afrikaans pop or the occasional American country song. Compared to the Spur and many of the brand-name restaurant chains in South Africa, it felt as if I had just crossed the border to another country. The food and wine were excellent.

Because whites are increasingly excluded from corporate and government sectors, they have to hustle to survive. They work long, stressful hours, sit in snarled-up traffic, and wives have little time to cook. That is partly why they spend a lot of money on takeout, and eating out. Spur got rich on the back of the white middle class, but is now betraying them by pandering to political correctness.

In a sense, buying power is the only form of power South African whites have left. Most corporations have decided that sometime in the future “there will be no more whites,” so they adapt their advertising to that forecast even now. Accordingly, it has become rare to see any whites on South African billboards or in corporate advertising, even though whites still represent roughly half the buying power in the country, especially for expensive or durable goods.

Whites must therefore write regular reviews of independent, white-owned restaurants like Buffelsfontein Beesboerdery, and freely promote them. We must create jobs for our own people, not for Zimbabwean migrants. The boycott could become a pro-white business movement!

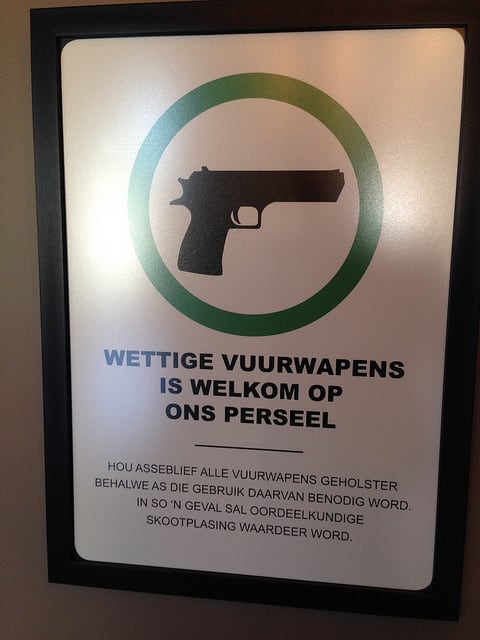

The owner of Buffelsfontein Beesboerdery clearly has a sense of humor. He put up a big sign at the entrance with the following caption:

“Legal guns welcome on our premises. Please keep all guns holstered except if the use thereof becomes necessary. In such a case judicious shot placement will be appreciated.”