James D. Phelan, Prophet of the Chinese Peril

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, April 14, 2020

“The Chinese, by putting a vastly inferior civilization in competition with our own, tend to destroy the population, on whom the perpetuity of free government depends,” James D. Phelan wrote in 1901. His article “Why the Chinese Should Be Excluded” added that Chinese immigrants are “indifferent to sanitary regulations” and therefore are breeders of disease. These words seem prophetic as Europeans and North Americans fight COVID-19.

It appears that people first caught the novel Coronavirus in a Wuhan “wet market.” The SARS outbreak of 2003 also began in a Chinese wet market. In these places, stalls are packed close together. Health regulations are lax. Live animals wait in cages, while butchers hack them up for customers. Blood sprays into the air and runs across the ground. Domesticated animals crowd beside wildlife sold illegally for medicine or food.

Phelan was not the only member of his generation who worried about the health habits of foreigners. While he was serving as San Francisco’s mayor, the British Empire was bringing proper sanitation to places such as India and sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The American military did the same during its occupations of the Philippines and Mexico, producing sharp reductions in cholera [2]. But Phelan’s support for the exclusion of Chinese immigrants went deeper than a concern about bad hygiene. He also wanted to exclude Chinese and Japanese because of their effect on wages and jobs.

James Duval Phelan was born in San Francisco on April 20, 1861. His parents had moved to California from Ireland for the Gold Rush. They stayed, and young Mr. Phelan spent most of his life in San Francisco. He attended a Catholic high school and graduated from the University of San Francisco in 1881. After earning a law degree and working as a banker, he was elected mayor in 1897.

James D. Phelan

Phelan was an Irish Catholic Democrat in a city run by Irish Catholic Democrats. He was also a civic progressive who led the Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco [3]. Unfortunately for him, his term as mayor coincided with the now-forgotten San Francisco plague of 1900-1909.

The plague began when a ship from Hong Kong docked in San Francisco in the summer of 1899. On board were two men with the Bubonic plague, which killed one-third of Europe’s population during the “Black Death.” When the plague began spreading in 1900, Mayor Phelan quarantined and cleaned up Chinatown. The plague returned after the earthquake of 1906, but Phelan’s energetic measures resulted in a relatively low death toll of 119 out of 121 total cases. (Before antibiotics, the death rate for the disease was very high.) [4]. It was during this plague that Phelan publicly denounced Chinese immigration. He also wanted to relocate Chinatown to the outlying Hunters Point neighborhood, but Chinese diplomats pressured Governor Pardee to quash the plan.

Phelan also wanted to keep out the Japanese. In an interview with the Boston Sunday Herald on June 16, 1907, he said that the “Japanese question . . . is not today a race question, but a labor question.” He added that “as soon as the Japanese coolies are kept out of the country, there will be no danger of irritating these sensitive and aggressive people.” As early as 1878, Dennis Kearney, the president of the Workingman’s Party of California, called Chinese workers “cheap slaves” who “are whipped curs, abject in docility, mean, contemptible and obedient in all things” [5]. Kearney, Phelan, and other nationalist politicians understood that thousands of cheap Chinese and Japanese workers would enrich corporations but cut wages for Americans. Most whites agreed.

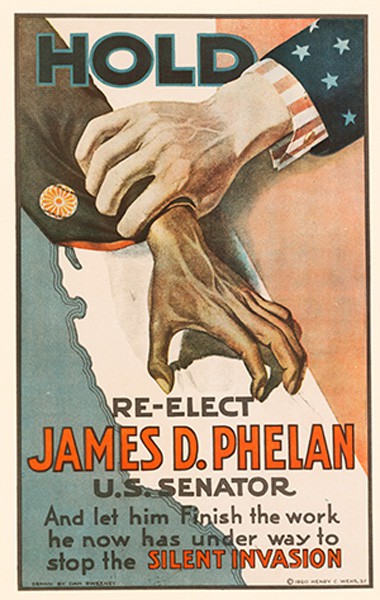

Thanks to men like Kearney, the Chinese Exclusion Act became law in 1882. During the presidential election of 1912, Phelan worked to persuade Woodrow Wilson to support Japanese exclusion as well. A year later, he supported alien land laws designed to limit the number of Japanese in the American West, and federal legislation in 1917 and 1924 stopped immigration from other Asian countries in addition to China. When Phelan ran for the US Senate in 1920, his campaign slogan was “Keep California White.”

One of Phelan’s posters from the 1920 campaign.

It is hard to believe, but early in the 20th century, Democrats in California campaigned to keep the state white. Phelan said in 1920 that stopping Japanese immigration to California meant that whites would not “be treated as the negro” [6]. This was because fewer Chinese “coolies” meant better wages and working conditions for white and unionized workers. Fewer immigrants from the slums of Hong Kong and Canton meant fewer plagues in California’s cities. So widespread was public concern over the growth of Asian influence in San Francisco that some Californians and other Americans considered the city “lost” by the 1920s. Los Angeles boosters marketed their city, built on “Anglo-Saxon virtue,” as an alternative to San Francisco and the immigrant-heavy cities of New York, Philadelphia, and Boston [7].

Phelan’s last great accomplishment came in 1924, when he joined Valentine S. McClatchy, publisher of the Sacramento Bee, along with the Japanese Exclusion League of California, in a successful campaign to lobby President Calvin Coolidge to strengthen Asian exclusion with that year’s immigration act. Phelan died in 1930, having accomplished a great deal.

America should return to its former policy of limiting Chinese immigration. Just as in James Phelan’s era, health is not the only concern. “Birth tourism” is a billion-dollar industry, and illegal Chinese immigrants in California dominate the trade. Our money-hungry universities admit many thousands of Chinese students every year, an unknown number of whom are spies.

We should produce our own hospital equipment and drugs rather than import so much from China. Americans now recognize how dependent we have become, but how soon will they forget once the threat of the virus has subsided? We should not be teaching science and technology to Chinese students, who will use it to compete with us. Nor should we hire them to work in high-tech or defense industries. China is an economic, military and — sometimes — a medical threat. James D. Phelan recognized this; so should we.

* * *

[1]: The British Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1 & 2, ed. Mark Doyle (Santa Barbara and Denver: ABC-CLIO, 2018): 129.

[2]: Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power, Revised Edition (New York: Basic Books, 2014): 100.

[3]: Mel Scott, The San Francisco Bay Area: A Metropolis in Perspective, Second Edition (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1985): 99.

[4]: Rebecca Rego Barry, “San Francisco’s Plague Years,” Science History Institute. 10 Sep. 2019. Web.

[5]: Dennis Kearney, President, and H.L. Knight, Secretary, “Appeal from California. The Chinese Invasion. Workingmen’s Address,” Indianapolis Times, 28 Feb. 1878.

[6]: Roger Daniels, The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 83.

[7]: John Butin, L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America’s Most Seductive City (New York: Harmony Books, 2009): 12.