A Conversation with Arthur Jensen

American Renaissance, August and September 1992

Arthur Jensen gave this interview to Jared Taylor in 1992. It is still as timely and relevant as the day it was recorded.

Arthur Jensen

Arthur Jensen is Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is perhaps the world’s best-known scholar in the field of racial differences in intelligence. Ever since 1969, when his article, “How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?”, appeared in the Harvard Educational Review, he has been at the center of what is probably the most controversial of all academic fields. Prof. Jensen has been widely reviled, but his patient research and keen analysis have now won a position of near-unanimity for his views — at least among specialists.

What follow are excerpts from a several-hour conversation with Prof. Jensen, in which he talks about race, intelligence, sex differences, eugenics, and the future of the United States.

American Renaissance: You are probably most famous, still, for that Harvard Educational Review article.

Prof. Jensen: That’s true, yes. I think that’s probably one of the most over-cited articles in the history of psychology.

AR: Well, I’ve always assumed that article got the incredible amount of attention that it did because this was really the first time after the Second World War that someone had stated that there could very well be a genetic factor that accounts for the difference in black and white achievement.

Jensen: Right, yes. It’s the first time that it had really been stated explicitly in the academic literature since before World War II.

AR: Why were you the person to first do that? What prompted you?

Jensen: I became involved in this subject the year [1967] that I spent at the Center for the Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, the Palo Alto [CA] think tank. I went there that year to write a book on the psychology of the culturally disadvantaged. I felt that I should have one short chapter about the inheritance of mental ability, if only to dismiss the subject. That was the standard stance at the time.

AR: That was your view at the time?

Jensen: Yes, that was my view at the time. I knew next to nothing about the subject, except that I had heard Sir Cyril Burt give the “Walter Van Dyke Bingham Address” at the American Psychological Association. I’d mainly gone just to see the most famous British psychologist. I wasn’t interested in the subject particularly, but it stuck with me because it was a brilliant lecture.

There also happened to be a geneticist at the think tank that year, and I became acquainted with him. He put me on a sort of reading course in this area so that I could learn more about it, the technical aspect of it. It was the year after that that I wrote the HER [Harvard Educational Review] article, in 1968, and it was published in the Spring of 1969.

And it was there that I met [William] Shockley. We got together periodically to talk about some of these things.

AR: Dr. Shockley had taken a public position on these questions before you had?

Jensen: Oh, yes; in two talks. One that he gave at the Commonwealth Club, here in San Francisco, and one that he gave at the National Academy of Sciences. This was in 1967. It was the first time he stuck his neck out on this.

AR: What do you think accounts for the ferocious opposition to your views — especially then — but which continues up to today?

Jensen: It continues today, yes. For one thing, people have been taught from early childhood — and it’s especially true of better-educated people — that all people are essentially the same, except for very superficial differences due to their social background and advantages in upbringing and so forth. To suggest anything else offends this deep conviction. In fact, I was brought up very much that way. My own parents, especially my mother — my father was more hard-headed and tough-minded — but my own mother thought it was just outrageous that I had written that HER article. The view being a very common one today, still, that blacks would be no different from the rest of us — the rest of the population — if they simply had the same education and all of that.

Even among a single racial group there’s a great sensitivity about individual differences in the trait of intelligence. This is probably the most highly valued trait. When people are asked what characteristics they want their children most to have, the two things they mention first are good health and good intelligence. If you suggest that people differ in intelligence for reasons that they themselves are not responsible for, because of the particular assortment of genes they happen to get, this seems terribly unfair.

AR: There’s an aspect of this that’s particularly curious, and that’s the fact that at the turn of the century there was a very strong acceptance, it seems, or a very strong movement towards acceptance of genetic differences by men like Sir Francis Galton and Karl Pearson. Even in the United States, very reputable people became advocates of eugenics.

Jensen: I think that World War II was really the main turning point in this. We’d been headed in that direction [egalitarianism], but the turning point, I think, was the revulsion against the Nazi Holocaust. People pointed to that as an example of what would happen if we recognized differences.

Of course it’s very inapplicable really, because the group that was persecuted there was the group that was doing very well in Germany and around the world. It had a larger percentage of Nobel Prize winners and members of the National Academy of Sciences and Fellows of Royal Societies than any other group.

AR: It’s my understanding that in fact there’s no record that Hitler even said that Jews were inferior anyway.

Jensen: That’s right, yes. They had other reasons for their views. But this [the Holocaust] was still given as an example of the result of making racial or ethnic distinctions between groups.

AR: I know that in the past Stephen Jay Gould, Leon Kamin and a few other people have been widely and popularly quoted as maintaining a strictly environmental point of view.

Jensen: That’s right. Well, certainly Kamin does; I’m not so sure about Gould. He does on the race difference issue, no doubt about that, but on individual differences in intelligence he doesn’t seem to be a strict environmentalist. He’s too much of a biologist for that. Kamin is, but whether Kamin believes this privately or not, I can’t be sure. He seems to me to be too intelligent to really believe what he says.

AR: You think that what he says might very well simply be what he thinks people should think?

Jensen: I think so. I think that is probably it. But then, I can’t accuse him of that, because that would be accusing him of dishonesty. I know he’s a very learned and bright person, and he’s a sane person basically, which some people in the opposition aren’t.

AR: Well, I guess what I’m driving at is whether or not there really are any people left in the psychometric community, or in intelligence testing, or serious applied biology, who do think — and are willing to say publicly — that racial differences in achievement are strictly a matter of environment?

Jensen: I know almost none myself. I’ve looked for such persons. When my book Bias in Mental Testing came out in 1980, Time magazine ran a full-page story about it. Then they got so many complaints about that article because it didn’t tear down my position at all. The same writer called me and said that they had gotten so many complaints that they had promised people they would bring out another article on the same subject after a certain amount of opinion had accumulated about my book. They would report this and it would satisfy the opposition.

Then they called me perhaps a month later and asked me if I could suggest anyone who might disagree with the main conclusions of this book, because they hadn’t been able to find anyone. I said, “Well, have you contacted Kamin?” And I mentioned a couple of other people. They said, “Yes, we thought of them first, but what they have to say sounds so weak that it wouldn’t satisfy our readership that we’ve done a job on this thing. Is there anyone else you could suggest?”

So I mentioned a couple of very competent psychometricians around the country. I didn’t know quite what their stands were, but I knew they were competent people who would be capable of criticizing this type of work and would likely have seen my book by that time. They called them, but they got nothing that they could use against me, so they never did the article. Now that would have been news itself, but it didn’t make the news.

One person who takes the opposite side on the race issue, not on the [test] bias issue, but on the race issue particularly, who I think is a respectable scientist, is James R. Flynn. He’s in New Zealand, at the University of Otago. He’s a professor of Political Science. I don’t agree with everything [he says] and I think he weights different items of information very differently than I would, or many others would. But he does seem to be a sensible and intelligent person without any very obvious ideological ax to grind.

AR: It sounds as though, in effect, you have to go all the way to New Zealand to find someone who is not an obvious ideologue with an obvious ax to grind who will take a reasoned and intelligent position that is opposed to yours.

Jensen: That’s right, yes.

AR: I understand that there are more or less physiological assessments of intelligence — reaction time correlates with height and myopia [all of which correlate with intelligence]. It seems to me, if the general public, or perhaps more importantly, the people who run the media, are to be made to accept the notion of genetic origins of individual and perhaps racial differences, then something like direct physiological assessment might be more convincing to them than IQ tests.

Jensen: Oh, I think so, yes. You see the black/white difference is mainly a difference in this g factor that I talk about. The term was invented by [Charles] Spearman

way back in 1904. If one does factor analysis on a whole battery of tests to determine the degree to which each of the tests measures this general factor that’s common to all cognitive tests — I don’t care what the test is; it can be as bizarre as anything you can imagine — if it measures cognitive ability, if it measures some kind of mental effort, however slight or however varied, it will measure this gfactor. Those g loadings, as they’re called, of the various tests, will predict quite well the degree to which whites and blacks differ on that test. Blacks and whites differ hardly at all on some tests, but they differ a lot on others. The thing that predicts the size of the black/white difference is the g loading of the test. Really nothing else, for all practical purposes.

AR: Can you describe in words the ones that tend to be the most g loaded?

Jensen: Yes. One of the best tests for measuring g is Raven’s Progressive Matrices. I can show you one right here. [Prof. Jensen describes the test — it involves recognizing patterns and making a selection that conforms to that pattern.]

Everyone is familiar with these kinds of shapes. There is nothing at all esoteric about these things as there would be with, say, a vocabulary test, where the words keep increasing in difficulty because they become rarer words. It’s really a test of true reason. It’s really inductive reasoning. It measures nothing but g plus error. There’s nothing verbal, nothing numerical, nothing spatial, nothing mechanical, nothing musical. I mean it’s just pure g.

AR: How do people who argue that test results are a function of bias in the test respond to a test like that? I can’t understand how there could be any cultural bias.

Jensen: Well, they will claim there’s cultural bias in doing this kind of activity. If the test were really culturally biased one thing we would notice would be that the items in this kind of test should be in a different rank order for different racial-cultural groups. I mean what’s hard for one would be easy for another and vice versa. But the rank order of item difficulty on this is exactly the same for blacks and whites.

AR: In other words, you can’t pick out particular questions that seem to be prejudiced against blacks?

Jensen: That’s right. Take the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), for example. This is an interesting one, because again the items in it are also the same for blacks and whites tested in this country, but if you take the PPVT, which was standardized on Americans, and give it in England, as I have done, you find that there are certain items that are way out of rank order of difficulty.

The way the test works, there are four pictures on each page, and you name one of them and the child simply has to point to it. Well, there’s one item that something like 75 percent of grammar school kids in this country get right, but Fellows of the Royal Society that I tried it on in England, flunk. It’s a picture of a caboose. You say “caboose”, and they look puzzled. I’ve tried this on Francis Crick [discoverer of DNA and winner of the Nobel Prize], and he said, “There is no caboose there.” I said, “Do you know what a caboose is?” He said “Yes, it’s a ship’s kitchen.” I said, “Sorry, that’s not right.” He said, “Well, I’m sure it’s right.” And he took down the Oxford English Dictionary and showed me that in England “caboose” means a ship’s kitchen. So that’s a true cultural difference, you see.

There are quite a few items that are of different difficulty in England, but it’s not true in this country. We tested hundreds of black and white children on the PPVT, and the item difficulties are the same rank order, except that fewer black children get any single item right.

AR: So those that argue cultural bias are reduced to arguing that the entire process is”

Jensen: The entire process is somehow biased, yes. That inductive and deductive reasoning is itself a cultural invention and it is biased against blacks.

AR: That seems a bit of a stretch, doesn’t it? That’s almost like saying that intelligence is somehow biased against blacks.

Jensen: That’s right, yes.

AR: It reminds me a little bit of the Ptolemeic Solar System, in which having assumed that the earth does not move, then people had to come up with increasingly hair-brained schemes to explain the apparent motions of the planets.

Jensen: Absolutely, and there’s sort of an infinite regress of this sort of thing. You have to make up one fiction to explain something, then you need another fiction to explain that fiction, and it goes on and on. This affects branches of psychology that are nominally totally disconnected from this issue. Things way out here someplace can’t be dealt with honestly because that fiction is a support for some other fiction. The bottom line turns out to be that we can’t face the prospect that there are real differences between the various racial and social groups. It’s really quite incredible.

AR: I have always thought that given this human genome project, that we can’t help but stumble on genes, that in certain combinations, result in intelligence.

Jensen: Right, yes. That is already a subject of research. Robert Plomin, at the State University of Pennsylvania, is actually researching this now with modern techniques of molecular genetics. He’s looking for specific genes that influence intelligence. It will be a difficult project, but this will eventually happen. Of course, when we do find those genes, I think that’ll probably settle the race differences issue, which can’t be settled by any known techniques of quantitative genetics, mainly because all of those techniques are for studying the heritability of individual differences in intelligence within racial groups, and it is highly inheritable within all racial groups that have been studied. There’s no question that the preponderance of the variance in intelligence — the g, more so than IQ — is attributable to the genetic variance.

But you can’t use the same techniques to study racial differences, because all these techniques are based on a comparison of relatives — twins, identical twins, fraternal twins, siblings, parents and children. You don’t find pairs of identical twins where one’s black and the other’s white, so there are no known ways in quantitative genetics for studying this, short of one that’s technically possible but practically unfeasible — to say nothing of the ethical objections. It would be something like a true breeding experiment such as they do in agricultural genetics.

There would have to be random samples of the white and black populations mated at random. Then the children cross-fostered at random in black and white homes. You’d have a complete experimental design of children whose parents are both white, both black, mixed white and black, and children who were reared in each type of home. Then if that were all thrown into what is called an analysis of variance, those data could be analyzed and one could sort out the degree to which the differences on any trait were attributable to genetic factors and environmental factors.

AR: So you could design an experiment that would give definitive data?

Jensen: Oh, right. No doubt about it, but it’s an experiment that simply couldn’t be done.

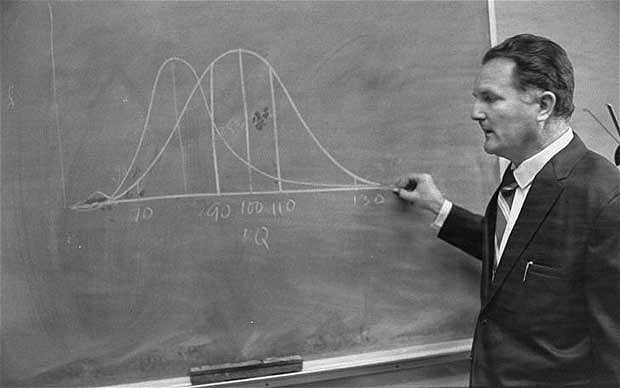

AR: Well, to raise another question about intelligence: it’s my understanding, although I’ve never seen it written about very much, that although the average male and female IQ is the same, the variance for men is greater.

Jensen: That’s absolutely true, yes. All of the data show that.

AR: Well that seems to be a thoroughly suppressed bit of data also.

Jensen: In some circles, yes. Although nearly everyone working in the field knows of this.

AR: But it seems to me that it’s important in so far as out at the tails of the curve — doesn’t that mean that the number of men with IQs of 160, say, could very well be five or six times greater than the number of women with IQs of 160?

Jensen: Right.

AR: Which seems to me would explain the kinds of things egalitarians are so often complaining about.

Jensen: Right, few women mathematicians and musical composers.

AR: Perhaps that’s explained as much by the difference of IQ in these tails [of the distribution curve] as anything else.

Jensen: Yes. Julian Stanley is a professor at Johns Hopkins University who, for 25 years has been conducting a nationwide talent search for high level mathematicians. He finds these kids when they’re anywhere from ten to fifteen years of age and he gets them into universities. He finds very few women each year, very few girls. The top fifty are always males. He goes through at least fifty males before he finds a female who’s next in rank.

These females who are selected into this program — he’s only interested in maybe the top 100 each year that he can find in the whole nation — but the females are the best in their schools. I mean they’re not girls who didn’t like math; they’ve loved it all their lives. They are the best in their schools. They are math whizzes, but there are always fifty or so males ahead of them in math talent.

Now, the same may be true in musical composition talent, because there’s no prejudice against women writing music, as far as I know. Women write novels and poetry, and there are a lot of women composers. I found a whole book in the library of biographies of women composers, but you probably haven’t heard of more than a couple of them, and

you’d have to name fifty male composers, at least, before you got to one that was on a par with the most famous woman composer.

AR: And you feel that that’s probably a reflection of their talent for composing?

Jensen: Yes, I think so. How would you explain that in terms of some cultural bias? You could explain it in the case of musical performance, let’s say — that the audience or the public doesn’t accept a woman pianist. But there are great women pianists, great women violinists, but there are no great women composers. There are no great women mathematicians, and there are no great women chess players. Those are the three fields in which there is a distinct sex difference — probably not at the middle — but at the top, and they are the three fields where there are authentic child prodigies, about the only ones where you find children who can outperform most adults who’ve devoted their lives to this kind of thing.

AR: Well, the sorts of things that you’ve been telling me, the sorts of things you’ve been doing research about, can you and do you freely teach these things in your classes?

Jensen: I sure do. I soft-pedaled things 20 years ago, and even then, there were great protests. I had students who would drop the course if these things were brought up even in a very mild way, in a hypothetical way. Students today wonder what all the shouting was about.

AR: Is that so?

Jensen: Yes, it’s rather hard to get students to believe that there were these protests and so on. They take a lot of this for granted. Oh, there’s been a great change in the students in that respect . . . But even in 1969-1970, I never saw a black in any of these demonstrations.

AR: Is that right?

Jensen: Not a one.

AR: They were SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]-types?

Jensen: All SDS and Progressive Labor Party, mainly. I tried to put them out when they tried to audit my course, because they were hecklers, and so some of the SDS people would sign up for the course. Of course, then they’d have to do the assignments and take the exams.

Interestingly enough, they usually were the top students in the course because they did so much outside reading to try and give me a bad time. They would go out and read everything Galton wrote! They were bright students. They just happened to be political radicals. “

Years ago, if I gave talks at the APA or the American Educational Research Association, the least little thing you’d say, people would get up on the floor and start denouncing you. I haven’t run into that for a long time, except in Canada and Australia. There’s about a ten year cultural lag in those places, I think, on this topic.

AR: I guess nowadays, as compared to fifteen or twenty years ago, you’re not a notorious presence on campus? People don’t say, “There goes Jensen!” You just don’t get that anymore?

Jensen: No, no. I used to. I used to have to be accompanied around campus by two campus policemen. In fact, they told me not to leave my office and go to the library, or any place, except to go to the men’s room around the corner, but not anywhere else without calling the campus police. They’d whiz across campus in a car and they’d be here in just a couple of minutes and walk with me wherever I wanted to go. One year I had two campus policemen, plain clothes men, in all my classes. They audited my courses.

American Renaissance: What about traits other than intelligence being differently distributed from group to group?

Prof. Jensen: Well, I think that’s very likely, too. It just hasn’t been studied very intensively. I think it’s interesting, for example, that nearly any famous concert violinist in this century that you could name is Jewish. It’s partly cultural, because there are so many famous Jewish musicians that Jewish parents tend to give their children music lessons to see if they’ve got one of these talented kids, so there’s something in the selection process there, too, but I think there’s undoubtedly a genetic factor in being a [Jascha] Heifetz or a [Fritz] Kreisler, or something like that.

AR: I know that in their book, Crime and Human Behavior, Prof. [Richard] Hernnstein and Prof. [James Q.] Wilson talk about — they’re very tentative about this, but — a possible difference in levels of impulsiveness in groups. They see an unwillingness to defer gratification as a psychological predisposition, one of the predisposing factors to crime. They suspect that traits like that could be distributed differently from group to group.

Jensen: Right. Any personality trait of that measure you examine, of course, has a genetic component, which means that it’s conceivable that groups can differ on such a trait for genetic reasons. Again, like intelligence, there’s no good way of proving this with the present technology in genetics, but it’s a plausible hypothesis, certainly.

AR: To get back to the intelligence question again, if society were to recognize the genetic origin of intelligence to the extent that you think it should, can you sketch out for us some of the things that society would do differently?

Jensen: There has to be much more emphasis than there is now on a more highly differentiated educational system — an educational system that allows people to develop to the maximum in whatever way their own potentials and abilities allow. So you would have much more educational diversity. You wouldn’t expect the same goals for everyone. Another would be a difference in the timing of the introduction of educational materials. There’d be a greater recognition of something that used to be called educational readiness for learning. We know that children differ enormously in their readiness to learn to read, to deal with numbers, and so forth.

Nearly all children within the normal range — by that I mean IQs of 70 and up, who don’t have organic brain damage and aren’t severely retarded — they can learn to read, provided it’s introduced in the right way at the right age. If you introduce a child who is in the 80 or so IQ range to reading at the usual age of six, he’s much more likely to fail than children with IQs of 100 or higher, and much more likely to be given up on by the time he’s at an age at which he could read with the same level of facility as the average six-year-old — that is to say, when he’s nine or ten. The average black entering first grade is about a year behind in level of development. A year is a crucial difference when it comes to readiness for reading and arithmetic.

AR: It’s my view, and this is a somewhat radical one, that a sense of racial difference, even independent of actual measurable differences, is sufficiently great so that any society that attempts to build a multi-racial nation is setting up what may be an insuperable obstacle for its own development. I think that to an unfortunate degree the mere fact of racial differences is something that human beings are almost always conscious of. For that reason, a society such as the United States, that is deliberately and explicitly trying to build a society on the notion that race can be made not to matter — which is in fact the unspoken assumption in America today — is doomed to failure.

Jensen: Now what if you had different racial groups that are compatible in abilities, general values and standards of living, as the Asians here seem to be? I mean, they’ve been conspicuously successful in our society, and what problems they’ve had have largely stemmed from their success.

AR: Well, it seems to me that if there are two racial groups that can live side by side in harmony, it appears to be whites and Asians. But the way our immigration policies work today, 90% of legal immigrants are non-white, overwhelmingly Hispanic, and it seems to me that the U.S. is making a terrible mistake by continuing to mix people from all the corners of the world who are as disparate as people can possibly be. It seems to me that one doesn’t necessarily have to posit racial differences in intelligence or characteristics to nevertheless fear for the future, perhaps even the survival, of a nation that pretends that race doesn’t matter.

Jensen: That may be true. But again, I’m wondering about the degree to which differences in basic characteristics may be at the basis of that. Where the differences in basic characteristics are not conspicuous, as in the case of Asians and whites, and when persons can fit in and do the same kinds of jobs and do them as well as anyone else, it may work. See, there are blacks who fit in this way too — who do all right.

But the black population in this country is in a sense burdened by the large number of persons who are at a level of g that is no longer very relevant to a highly industrialized, technological society. Once you get below IQs of 80 or 75, which is the cut-off for mental retardation in the California School System, children are put into special classes. These persons are not really educable up to a level for which there’s any economic demand. The question is, what do you do about them? They have higher birth-rates than the other end of the distribution.

People are shocked and disbelieving when you tell them that about one in four blacks in our population are in that category — below 75. Judge Peckham [in a case in which he ruled that black students in California could not be given IQ tests because the tests were biased against blacks] could not believe it when this was explained to him in a trial that lasted a year. He said, “Well, if there were twice as many blacks in classes for the retarded as whites, maybe that would seem not impossible, but since there are four times as many, there’s got to be something wrong with the tests. There’s got to be something wrong with the way you’re classifying them.”

AR: Well, what do you think should be done?

Jensen: Well, as Lloyd Humphreys said — he’s a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois who testified at the Larry P trial [about IQ tests for blacks in California] — the best thing the black community could do would be to limit the birth-rate among the least able members, which is of course a eugenic proposal. He was testifying on the side of the state; he knows the tests aren’t biased. The defendant in the case was, of course, Wilson Riles, State Superintendent of Public Instruction [on whose side Prof. Humphreys was testifying].

Riles denounced this testimony in no uncertain terms. He said he’d never heard anything so racist in his life. He made a public statement about it and denounced Lloyd Humphreys for making this reasonable statement. Humphreys pointed out that one doesn’t even have to talk about genetics. One only has to look at the raw correlation between parents and children. Whatever the cause, it would be better if these people did not have as many children because the children tend to turn out pretty much like the parents.

You see, the problem with relying entirely on education in these matters, is that these measures don’t get to the IQ group below 75. Even when it does get to them — maybe I shouldn’t mention his name, but a noted psychologist probably known to you — pointed out to me that somehow g also involves being able to act on what you know. He gave as an example the fact that everyone knows about AIDS today, yet there are many people who are taking no precautions against it and are behaving as though it didn’t exist, and you can’t say it’s because they haven’t heard about the danger.

AR: Although that’s what people continue to say. They seem to say the answer is more education, more targeted propaganda.

Jensen: Well this works for the above 90 IQ part of the population. It is probably effective for them. But it doesn’t get to this other group. The rate of AIDS in the black population of the United States is increasing much more rapidly than in any other segment of the population. In the homosexual population, which is not differentiated from the rest of the population in intelligence, the rate of AIDS is going down. I mean the message has gotten to them, apparently.

The message is really, probably, getting to just about everyone, but people in the lower part of the distribution don’t seem to be able to have enough g to put messages together in a way that influences their behavior. This is one of the reasons why all methods of birth control, except sterilization, are dysgenic, because the effectiveness with which they are used is related to g. There’s no getting around it.

AR: Do you think the state has any right to or role in stepping in in a forceful way?

Jensen:Well, that puts me into a political arena, if I make any pronouncements on that. My personal opinion is that I think society has to protect itself from dangers without and dangers within. I don’t think it can survive otherwise. I think the dysgenic effect that Shockley was worried about may become so evident one day, that when everything else has been tried and found not to be effective — importantly effective — people will realize that something has to be done at a political and governmental level. Because education will not do the job in a large segment of the population.

AR: Well, it seems to me what you describe as a possible future for the United States, namely one in which the dysgenic effects become so overwhelmingly obvious that we have to do something, is a terrifying prospect.

Jensen:It is. It absolutely is. I’ll send you a letter I received from someone who has to remain anonymous, that talks about these things. I’ve shown this letter to a number of other professors and they shake their heads and say they’re afraid it’s all too true. This person sort of predicted this thing going through stages, one stage being where the society becomes rather racially divided and lives in almost sort of enclaves that are protected one from another. You have a lot of that going on in countries like Brazil now.

I visited a professor in a large Eastern city last year, spent a couple days with him, and found that he lives in a protected community like this. I mean it’s a community within the outskirts of the city that’s completely fenced in and has a guard. You have to go through a gate. If you’re a guest of someone they have to phone him to see if that person’s expecting you or knows you. It’s like a prison, and these people live that way. People are just moving into these kinds of places because it’s unsafe to be anywhere else.

AR: It’s the same in Miami. Miami has many of those enclaves. The curious thing to me is, if one were to take, say, someone of my grandfather’s generation — the expectations he had for society, the kind of life he led, the assumptions he made about the way human beings should behave — if he were to come here today he would probably say, “My gosh! The dysgenic effects are so obvious, we must act now!” In other words, because it happens slowly, we accommodate ourselves bit by bit.

Jensen: It’s like the story of the frog that’s put into a bucket of water that’s gradually heated up, it finally gets cooked, never jumps out. You throw him in some fairly warm water, he’ll jump right out instantly. I think our population is becoming habituated to conditions that would have been thought ghastly a generation ago.

AR: Yes, sir. I think so too.

Jensen: It’s clear to me, I mean I’m old enough to believe that the quality of life has deteriorated in the United States over the last thirty years.

AR: I wonder how far things must go before people decide that something must be done.

Jensen: There’s a possibility that they may go to the limit and nothing will ever happen. I mean look how far they’ve gone in Brazil, Rio de Janeiro.

AR: At the same time, I think that there could very well be in countries — in Asia, Lee Kwan Yu [of Singapore] has suggested eugenic . . .

Jensen: Oh yes, he’s dealing with a very different thing. He’s got a small island community there and a small population, and it’s racially quite homogeneous. All they’ve got there are 80% Chinese, 15% Malaysian, and 5% Indian, and the Malaysians are still getting out. Those who can’t make it go to the mainland. So he’s had it easy that way. He’s certainly got one of the few spots in the world where you’d feel safe today walking in the streets.

AR: Japan is another. I think it’s not inconceivable that a country like Japan, if it started giving even relatively mild inducements to more intelligent people to have more children and less intelligent people to have fewer children, it wouldn’t be long before Japan would be just an utterly dominant power.

Jensen: Right, well when China starts doing this — of course China’s now controlling its population. If they start using eugenic means to improve the quality of the population in various ways, which is sort of the next step, think where they will be with that size population to work on. They don’t have the severe space problem that Japan has.

AR: It just seems to me that everyone talks about [international] competitiveness, but no one dares talk about the genetic component, the biological component of competitiveness.

Jensen: But you know, every great society in history so far has lasted a certain length of time, and then something has happened. Greek civilization, the Roman Empire, the British Empire — so when things finally go down, some other part of the world becomes predominant.

AR: But can you take such a philosophical attitude towards your own civilization?

Jensen: Well, I’m merely interested in the preservation of civilization, regardless of where it is. Some people are so afraid, of say, the Asians taking over in this country. Well if they can take over and do a better job than the rest of us, if they preserve the great things of both Western and Asian civilization, well I don’t think the world will be worse off. Race and color and national origin and that sort of thing, don’t really matter much to me at all. I’ve just never thought along those lines.

My fear would be a nation that devolved to the point where the great things of Western civilization would be lost. I’d hate to think that Beethoven would be lost to all except some small elite, and that these things could only be accessible on recordings and laser discs and so on. I like the idea of having an opera house where I can go and see Wagner, Verdi, and Puccini. I think that the Asians are capable of preserving that level of civilization, once introduced to it.

My fear is that if the population deteriorates to the point where there’s no demand for these things, then that part of our culture is lost, at least here. Maybe it will be preserved somewhere else in the world. The fruits of genius, wherever they’ve occurred in the world, have to be preserved for future generations. It’s conceivable you could have a country, or maybe even the world, in which these things become irrelevant because people are more concerned with creature comforts, overpopulation, and pure survival.

AR: That to me would be a catastrophe and a tragedy of unparalleled proportions.

Jensen: Oh, absolutely!

AR: I can think of nothing worse, really.

Jensen: Evolution itself doesn’t care. These things are a product of evolution, and they’ve just, by some kind of fluke, reached this point — I mean, unless one takes a religious view of this, which I don’t — they’ve reached this peak of having Beethovens and Wagners and Einsteins and Goethes and Shakespeares and so on. But then to move away from that to a population for which these things become meaningless, it would be just a tremendous tragedy. But it’s not an impossibility, because evolution doesn’t care what direction it goes in. It’s simply opportunistic.

This AIDS crisis is simply another opportunity for evolution, in a sense. That’s what’s going to happen. It’s going to divide the population into those who can avoid AIDS and those who, for whatever reasons, can’t.

Prof. Jensen is the author of the definitive work on the validity of mental tests, Bias in Mental Testing (1980), and a more popular condensation of this book called Straight Talk About Mental Tests (1981). Some of his more recent views are reflected in “Spearman’s g and the Problem of Educational Equality,” which appeared in the Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1991. He is the author of many other publications and is currently at work on a book for the layman about his latest findings.