Frenchman, European, White Man

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, December 11, 2015

Dominique Venner, The Shock of History: Religion, Memory, Identity, Arktos Media, 2015, 160 pp., $21.00.

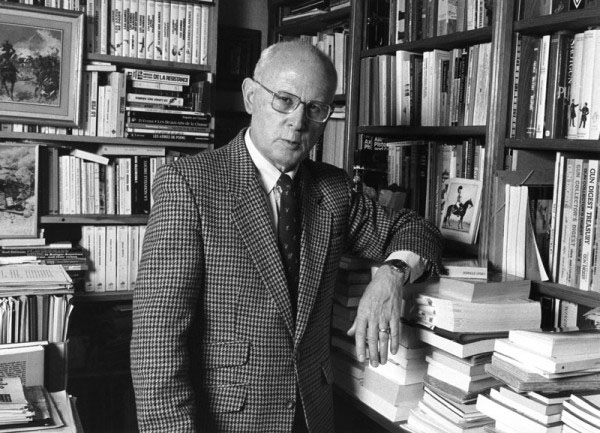

On May 21, 2013, a Frenchman virtually unknown outside of Europe suddenly burst into the consciousness of racially aware Americans. That day, Dominique Venner walked into the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris and shot himself in the head. As he explained in his suicide note, he took his own life as an act of sovereignty–of control over his own destiny–and in protest against what his beloved France had become: a husk of a once-great nation, whose rulers submitted to American dominance, celebrated a decades-long invasion by unassimilable foreigners, and had legalized homosexual marriage.

Venner was a political activist and also a prominent historian. He was awarded the Broquette-Gonin Prize of the French Academy in 1981 for “philosophical, political, or literary achievement that inspires a love for the true, the good, and the beautiful.” Yet, until his death, none of his work had been translated into English. Thanks to the indispensible work of Arktos Media, this slim volume–composed for English-speakers–makes a few highlights of his thinking available to new audiences.

Venner had two great advantages as a historian: He did not just study history, he participated in it. He was also among the tiny handful of intellectuals who understood tribe, nation, and race, and who grasped the horror that Europe is inflicting on itself. Venner’s experience and insight shine through every page of The Shock of History.

Dominique Venner was born in 1935 and joined the French army the first day he became eligible: his 18th birthday. He served as a paratrooper, fighting the Algerian insurgency. In 1956, after three years of combat, he returned to France, where he was active in nationalist politics. That same year, he helped raid and ransack the headquarters of the French Communist Party to protest the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian uprising.

Later, Venner took part in the attempted coup against the French government when Charles de Gaulle–in Venner’s view–betrayed France by supporting independence for Algeria. Venner was imprisoned for 18 months as a “political undesirable,” but his experiences gave him rare insights. As he writes in this volume, “It is total immersion in action, with both its most sordid and noble aspects, that has forged me and given me the ability to understand history from the inside, as an initiate, and not as a scholar . . . or as a spectator.”

After his release in 1962, Venner began his career as an intellectual. He worked with the main figures of the French New Right until 1971, from which time he devoted himself to history. He wrote about the traditions of Europe, the French resistance during the occupation, the Russian civil war of 1918 to 1921, the Confederacy’s struggle for independence, and many other subjects. His French Academy prize was for History of the Red Army.

Venner also wrote handbooks about weapons, as well as a book on hunting called Dictionary for Those Who Love to Hunt. As he explains:

To my mind, hunting is not a sport. It is a necessary ritual in which every participant, predator and prey, plays the role imposed upon him by nature. Along with childbirth, death, and seed-sowing, I believe that hunting, if practiced according to the rules, is the last primordial rite to have partially escaped defacement and manipulation at the hands of rational, scientific modernity.

The fate of Europe

But history was Venner’s great passion. These are the first words of this volume: “The shock of history: we live it neither knowing it nor comprehending it.” And yet Venner devoted his life to trying to know and comprehend. “History is knowledge of the past,” he writes, “but this knowledge is not neutral. It incites reflection on events of the past in order to illuminate the present.” Venner writes that objective history is a European invention. Homer laid the foundation for what Herodotus and Thucydides were the first to practice.

Venner probed Europe’s past because he loved Europe and its people. He believed that no one could understand any people or culture unless he completely rejected universalism:

Men exist only by what distinguishes them: clan, lineage, history, culture, tradition. There are no universal answers to the questions of existence and behavior. Every civilization has its truths and its gods . . . . Every civilization creates its own answers, without which the individual, man or woman, lacking identity and archetypes, is thrown into a world of chaos. Like plants, men cannot exist without roots. Every individual must discover his own.

Universalism is a dangerous illusion because “it stunts our ability to comprehend that other men do not feel, think, or live the same way we do . . . .” He writes that “higher civilizations are not simply regions of the planet, they are different planets entirely.” He urges Europeans to search for their own, unique “spiritual morphology,” because “a human group is not a people unless it shares like origins, in a specific location, commanding a space, giving it direction and a border between the inside and the outside. This location, this space, is not only geographic but spiritual.”

A people’s spirit is embedded in tradition, which comes from the past, but gives life and meaning to the present: “If a tradition survives over time, it is because it rests upon the hereditary dispositions of related people.” Europeans must steep themselves in their traditions because they:

make us who we are, unlike any other. They constitute our perennial tradition, our unique way of being men and women in the face of life, death, love, history, and fate. Without them we are fated to become nothing; to disappear into the chaos of a world dominated by others.

Venner believed that Homer marks the beginning of what is truly European: “My holy texts are the Iliad and the Odyssey, the founding poems of the European soul.” Homer is the best teacher for those “looking for the decisive categories of the European soul, those of action, knowledge, beauty, excellence, and tragic wisdom.”

Venner also argues that the world itself is a standing refutation of universalism. Wherever we look, non-Europeans reject our ways and are incapable of adopting them. But the inability to reject universalism could prove fatal to Europe: “After having colonized other peoples in the name of universalism, Europeans are now in the process of being colonized in the name of the very same principle–against which they do not know how to defend themselves.” Because Europeans are unable to draw and defend spiritual and political boundaries, “Europe has been thrown, naked and defenseless, into a world aching to vengefully humiliate her.”

Why did Europe lose its nerve? Venner believes it was what he calls the repetition of the Thirty Years’ War, that took place between 1914 to 1945:

After the disaster caused by the two great wars, Europe entered into a state of ‘dormancy,’ crushed militarily, politically, and morally by her own mistakes, her quasi-suicide, and her terrifying and useless expense of energy and blood. Completely demoralized by the notion that European civilization could produce such horrors, the idea that it must be corrupt or cursed in some way began to creep into people’s hearts and minds.

Venner draws a parallel to the Opium War. Until then, China had never doubted itself nor its own civilization, but defeat shocked it into a headlong imitation of the West that led to the horrors of communism. In 1945, Europe had not only destroyed itself but was dominated by non-European powers: the Soviet Union and the United States. The result, writes Venner, is that “we have lost faith in our own values, which we no longer even know. We copy the American model, even as we criticize it, lacking the freedom to imagine a European future.”

Like so many European traditionalists, Venner is deeply suspicious of the United States. He mocks the idea of American exceptionalism, of “manifest destiny” and the “city on a hill.” He wonders how Emerson could have written that the United States is “the greatest favor God has ever granted to the world.” He continues: “These principles are never doubted by the American people. They are taught as dogma. Americans are told that they are representatives of the Empire of Good.”

Venner believed that America had degraded Europe with a rapacious form of capitalism that glorifies material possessions over everything else. Europeans have become Americans: “The zombie is happy. He is told he will find happiness in satisfying his desires, because his desires generate revenue.” Technological progress–America’s forte–is virtually all that remains of the European spirit.

But America’s greatest sin is to have promoted equality and to have built a nation that repudiated inequality and aristocracy.

The inevitability of inequality

Venner believed that healthy European societies need aristocrats who are conscious of their duties and prepared to sacrifice. He notes that before the First World War, with the exception of France, every major European power was a monarchy with an “active and modern nobility.” Nobility was not a matter only of birth but also of merit. It offered a higher ideal of duty, just as the Homeric heroes were models for the Greeks. The Prussian aristocracy, for example, believed that “freedom can only be conceived in relation to duty,” and that “solid education [was] passed down from one generation to the next, who would subconsciously interiorize the ethics of duty.”

Aristocrats understood that Europeans were all of the same blood and culture and that wars should be of limited duration and destructiveness. Venner writes that it was democratization and mass participation in politics that helped push Europeans towards national hatreds and unlimited war.

In this context, Venner writes admiringly of Clause von Stauffenberg and the other aristocratic leaders of the failed assassination plot against Adolf Hitler. “The only true German opposition to Hitler came from an aristocratic, Prussian military faction,” writes Venner, “composed partially of former National Socialists.”

Stauffenberg was inspired as a young man to join the army because of his fascination with Homer, the Greeks, the Romans, and the chivalric ideal. At first he supported Hitler, but was appalled by Hitler’s savage treatment of Russians and Ukrainians who could have been recruited to the German cause. He saw that Hitler was leading Germany to defeat and degradation, and he lead other aristocrats and traditionalists such as Erwin von Witzleben and General Ludwig Beck in an uprising he hoped would save Germany.

Shortly before the assassination attempt, Stauffenberg co-wrote a manifesto addressed to the leaders of the traditional Germany that he hoped would survive the war: “You seek a new nobility . . . You will recognize your brothers by the radiance in their eyes.” Venner argues that Stauffenberg knew his plan was likely to fail. He “knowingly acted in a self-sacrificial manner in order to prove that the ‘hidden and heroic Germany,’ of which he was the incarnation, morally condemned the blemishes of Hitler’s regime and called for a new Germany, wholly unrelated to the future Bundesrepublik imposed by the American victors.”

Venner adds that it was not a coincidence that one of the early acts of the American occupation was the obliteration of Prussia as a legal entity. Even in opposition to Hitler, the Prussian spirit of honor, commitment, valor, and personal responsibility was anathema to the conquering egalitarians.

Venner similarly admired Ernst Jünger, who wrote the great war novel Storm of Steel, and was one of the leaders of the Conservative Revolutionary movement in Germany after the First World War. Jünger, who also became hostile to Hitler, was a personal friend of Venner and died in 1998 at the age of 103. “His writings helped me to understand that the crisis facing the European people of today is not political,” Venner writes. “It is a spiritual and civilizational crisis that requires far more than just political solutions.” He adds that although aristocracy has disappeared as a social class, he found, in Jünger, that “the qualities of honor, self-sacrifice, and of noble conduct survive in those of elite character who, in decadent times, constitute a sort of hidden aristocracy.”

Until the end of his life, Venner believed that aristocracy could be reestablished, even though it would be “an immense revolution of ideas and education.” For this great task, he again turns to Homer:

When we live in the company of people who walk with nobility, if we are not of low-born disposition, we feel an impulsion. It is thus that Homer has left us our life principles; nature as our basis, excellence as our goal, beauty as our horizon.

Hope for Europe

Venner writes that the two alien blocs that dominated Europe during the Cold War froze Europe into immobility for 45 years. With the fall of the Berlin wall, history began to move again, and Europe is slowly rising from its state of prostration. “There seems to have been a general weakening of American power,” Venner writes, “which should be exploited by Europeans in order to snap out of their dormancy.”

But in order to regain its spirit, Europe must rediscover itself. It was this in mind that Venner wrote History and Traditions of Europeans: 30,000 Years of Indentity: “My stated intention was to lay the groundwork for a reformation through the discovery of our origins.”

But one handicap for Europe is that it does not have an identitarian religion. Venner believed that Christianity was an alien, Middle Eastern faith that does not promote European identity. He writes that it was the perfect, universal religion for a Roman empire that wanted to spread its mores along with its power. But Venner is not hostile to Christianity, noting that “the cathedral of Chartres is as much a part of my universe as Stonehenge or the Parthenon. . . . Christianity, alien to Europe in its origins, was transformed from the inside by our ancestors: the Romans, the Gauls, and the Germans.”

In any case, Europeans are falling away from the Church, and must replace it with a deep cultural identity that unites them spiritually. An identitarian religion ensures survival and even justifies conquest:

In the same way that some consider themselves sons of Shiva, Muhammad, Abraham, or Buddha, it is important that Europeans see themselves as sons of Homer, Ulysses, and Penelope. . . . Whether one is Christian, free thinker, or whatever . . . we must rise above political and denominational variables and rediscover the permanence of tradition, which has permeated our founding poems for millennia.

Venner admires Hindu nationalism, for example, because it is such a powerful identitarian force that the political follows naturally from the spiritual. At one time, the Catholic Church had a similar political-spiritual power in Europe, and was led by hard-headed politicians who were also servants of God. Venner was not sure Europe could ever recreate anything similar but even if it did not, he believed Europe would find the courage to save itself.

This short book is mainly about history, but Venner touches on other important subjects, including the Western view of suicide. It is clear from The Shock of History that Venner had already made up his mind to kill himself. He writes approvingly of Publius Spendius who committed suicide at age 53 in 210 AD “because he refused to live in a degenerate society that negated the Rome of his soul.” He quotes Antoine de Saint-Exupery, author of The Little Prince, whom he believes deliberately flew his plane into the ocean: “I hate my era with every fibre of my being . . . Man is neutered, severed from his original resonances . . . The termite mound of the future horrifies me. I hate their [the Frenchmen of his day] robotic virtues.”

Venner also salutes Admiral von Friedeburg’s decision to end his life after signing the capitulation papers for the Kriegsmarine in 1945, and wonders how the disgraced commander of the French forces who surrendered at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 managed to live out the rest of his life. For Venner, suicide is the noble course if life is no longer worth living. It is the ultimate act of power and control. If it is an assertion of autonomy rather than a cry of despair, it is “a proclamation of sovereignty over one’s very self” and is a right that should be “limited only by the sadness we might cause to those close to us, or by obligations requiring us to stay alive.”

But more important, suicide was Venner’s final act of service to his beloved Europe. It was a proclamation that “the world is entering into a new phase of history in which the historically unexpected has become possible again.” His dramatic death was a rejection of the view that Europeans “will allow themselves to be displaced.”

To the end, Venner had faith:

We will be forced to rise up and face immense challenges and fearsome catastrophes even beyond those posed by immigration. These hardships will present the opportunity for both a rebirth and a rediscovery of ourselves. I believe in those qualities that are specific to the European people, qualities currently in a state of dormancy. I believe in our active individuality, our inventiveness, and in the awakening of our energy. The awakening will undoubtedly come. When? I do not know, but I am positive that it will take place.