The Old College Try

Peter Bradley, American Renaissance, May 1, 2015

Jay M. Smith and Mary Willingham, Cheated: The UNC Scandal, the Education of Athletes, and the Future of Big-Time College Sports, Potomac Books, 2015, 280 pages, $26.95.

In the summer of 2010, the University of North Carolina (UNC) athletic department was caught up in a scandal. Many basketball and football players were found to have taken phony courses and to have been given high grades for papers they did not write and classes they did not attend. This had been going on for over a decade, and involved thousands of players. Cheated, by Jay Smith, a professor of history at UNC, and Mary Willingham, a UNC academic advisor and whistle-blower in the scandal, is a full account of this sordid tale of academic fraud.

The authors provide an abundance of evidence for bogus independent-study classes, inflated grades, plagiarized work, and an administration that deliberately ignored obvious fraud. All the cheaters were apparently black athletes, and many black professors were involved, but the athletes are portrayed as victims rather than beneficiaries of this fraud.

Students or athletes?

The problem of lowering academic standards to recruit athletes goes back many years. In 1939, University of Chicago President Robert Maynard Hutchins chose to eliminate the school’s football program rather than relax standards. “To be successful, one must cheat. Everyone is cheating, and I refuse to cheat,” he explained. This was when college athletes were nearly all white, and the problem has only gotten worse.

In 1986, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) enacted Proposition 48, which set minimum academic standards for athletic eligibility. A minimum score of 700 out of 1,400 on the SAT and a 2.0 grade-point average hardly seem demanding, but a number of coaches and black race activists decried the measures as discriminatory. And, indeed, a 1988 report found that 78 percent of the athletes who could not meet these requirements were black. Coaches quickly learned how to get around these minimum standards. This book shows how.

The center of the UNC scandal was the African and Afro-American Studies Department (AFRI/AFAM), and the chairman of the department, Julius Nyang’oro, an immigrant from Tanzania, was at the heart of the fraud. Prof. Nyang’oro enrolled athletes in AFRI/AFAM courses and made sure they got grades good enough to keep them eligible to play. Four of the five starters from UNC’s 1993 national championship basketball team were AFRI/AFAM majors. Prof. Nyang’oro got season tickets right behind the UNC bench.

Independent studies classes were a key part of the fraud. Independent study is generally reserved for talented graduate students who want to do work that is more focused than a typical course syllabus. Students are usually graded on a paper that reflects original research.

Needless to say, the UNC athletes were not producing original research, though in most cases they seem to have turned in a paper. Whether they actually wrote them is another matter. As the authors note, the purpose of AFRI/AFAM independent study was to give “virtually free grades to players who were valuable to their profit-sport teams.” These courses were popular; more than 2,300 students did AFRI/AFAM independent study from 1991 to 2011.

But how did athletes pass required courses such as English and math? UNC also has a foreign language requirement. How did students barely literate in English learn a foreign language?

Keep him eligible

Cheated devotes a section to the career of Julius Peppers, a star black athlete who played on both the football and basketball teams from 1998-2001. Mr. Peppers went on to a long NFL career and is still an active player at age 35. He did not earn a degree but was kept eligible thanks to the AFRI/AFAM department and other phony courses, such as Swahili and French drama, in which athletes got passing grades for little or no work.

At UNC, Mr. Peppers had to maintain a GPA of at least a 1.75, but when he took real classes he failed. He got Fs in Algebra, Earth & Climate, and World Regional Geography, and Ds in Applied Ethics, English Composition, and Stagecraft. It was his inflated grades in AFRI/AFAM courses (usually Bs) that barely gave him the GPA he needed to keep playing.

Football and basketball players had tutors, counselors, and advisers whose main job was to keep them eligible–even a D is better than an F. One of Mr. Peppers’s academic counselors, Carl Carey, remembers that basketball and football coaches were always after him to “keep him eligible, keep him eligible.” He then put pressure on faculty. In one case, Mr. Carey literally banged on the doors of a drama teacher’s office to get Mr. Peppers a second chance to take a test that he had failed. He got a D, which saved his eligibility.

Mr. Peppers case was not unusual. Another unnamed football player teetered on ineligibility despite earning 9 As, 8 of them in AFRI/AFAM courses, and the other in an equally corrupt class, The French Novel in Translation.

By the mid-2000s, Prof. Nyang’oro had abandoned all restraint. Confident that he would not be caught, he gave student-athletes As in “paper classes” for which they did no work at all. This particularly benefited the UNC 2005 national championship basketball team:

A single statistic underlines the enormity of the fraud from which the 2005 team benefited. A handful of players from the team took a total of thirty-one paper classes over a few semesters and summer sessions. All thirty-one grades awarded, without exception, were either A or A-. Rashad McCants, a star forward on the championship team, followed a paper classes-only schedule during the spring semester of 2005, meaning that he was relieved of all academic burdens in the season in which he pursued his national championship dreams. Perversely, McCants saw his GPA rise significantly–he even made the dean’s list after a semester in which he had done no academic work.

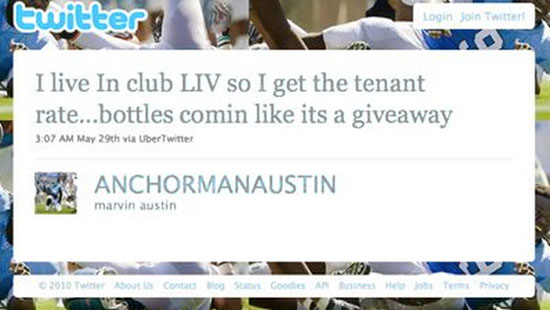

A 2010, a UNC football player named Marvin Austin tweeted about glamorous evenings at nightclubs with “bottles comin’.” This drew the attention of the Raleigh News & Observer, which investigated, and ran a series of articles on the fraudulent courses. The university’s response was, at best, a cover-up:

No instance was found of a student receiving a grade who had not submitted written work. No evidence indicated that student athletes received more favorable treatment than students who were not athletes. In addition, no information was found to indicate that the department personnel involved in these courses received a tangible benefit of any kind.

The NCAA gave UNC minor punishments, including the loss of some scholarships and a year’s probation for the football team. The Epilogue of the book notes that at press time the NCAA had announced a new investigation into “academic irregularities,” so further punishments may yet be announced. Prof. Nyang’oro retired in 2012, and charges against him were dropped in exchange for his cooperation in the investigation, though he should surely be the main target of the investigation.

Race

Race is a constant subtext to Cheated, and the authors profess to believe that black athletes were the true victims–they were “cheated” out of a college education. The book is full of liberal posturing:

Between the early 1990s and 2011 the Department of African and Afro-American Studies appears to have been on the receiving end of a form of racism that most often goes unacknowledged, a patronizing racism rooted in low expectations.

It is not only the uninformed and secretly racist sports fan who believes that African American athletes should feel ‘lucky’ even to be on a college campus.

Self-satisfied and privileged whites tend to chalk up classroom shortcomings among black athletes to laziness, lack of drive and ‘cultural’ issues.

Why would UNC tolerate a 51 percent graduation rate among black male athletes (versus 89 percent for the student body as a whole) unless its officials assumed that lower levels of achievement were to be expected of black students?

Not once does Cheated blame any of the black athletes who actually participated in and benefited from the cheating. Some of this is perhaps understandable. The book is full of black athletes who couldn’t pass even remedial courses despite an army of tutors and counselors. Perhaps the book could not even have been published if it also portrayed them as pampered beneficiaries.

However, black athletes are admitted to top universities despite not even coming close to meeting admissions requirements, they get full scholarships with free room and board, and end up with degrees they don’t deserve. This does not even include the “under-the-table” money and gifts they often receive from recruiters. These people are exploited and cheated?

Moreover, playing at a top school such as UNC means a chance to play professional sports. Even a few years in the NBA or NFL can mean millions. Julius Peppers has already spent 14 years in the NFL. Is he a victim or a beneficiary?

Although Cheated is all about race, it does not treat it directly. How many of the athletes involved in the UNC scandal were black? Were any of them white? The school has produced a number of white athletes, but Cheated does not mention a single white in connection with the scandal–though the mother of Tyler Hansbrough, a white basketball player, landed a make-work job at UNC when he agreed to attend.

Most college athletes are white, and play sports such as baseball, wrestling, tennis, or hockey. Were any of those sports involved in the scandal? How many black athletes actually earned their degrees? Did women athletes get special treatment or only men?

Cheated does not answer these questions, but it suggests that academic fraud almost exclusively benefited black football and basketball players.

Solutions

The authors offer two solutions. One is simply to pay college football and men’s college basketball players. Players could pursue degrees if they wanted, but they would not have to go to class at the school they supposedly represented.

What would feminists and Title IX advocates say? What would be the status of black athletes in other sports who couldn’t keep up their grades? Most schools lose money on football and basketball teams; would they still have to pay players?

Here is the book’s second solution: “Every university that plans to lower its admissions standards in pursuit of athletic glory should be required to develop an intensive literacy program that will ensure college readiness by the player’s second year in residence.” Good luck.

There is a third solution. Make athletes meet minimum standards on SATs and grades, and expel any who cheat or plagiarize. In other words, treat athletes like regular students. This works for wresting, swimming, hockey, baseball, field hockey, volleyball and all other sports.

It would mean far fewer blacks playing football and basketball, and there would be cries of “racism.” But quality of play might not decline that much. The college basketball national championship game this year featured an 80-percent white Wisconsin team against a Duke team that–though it had darkened considerably–won four national championships with mostly white teams over the last 24 years.

The scandals at UNC and many other major sports colleges can be understood only though the lens of race and racial differences, and despite the usual platitudes and hectoring, Cheated gives glimpses of the racial realities behind the scandal. But blacks as a whole simply cannot meet academic standards created for whites, and this makes a return to the tradition of the student athlete impossible. Scandals such as the one at UNC are likely to continue.