Justices Reconfirm: Discrimination Against Whites is OK

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, June 25, 2013

The Supreme Court’s decision in Fisher v. University of Texas has generated headlines about “compromise” and “partial victory for the foes of affirmative action,” but it is not that at all. It is an out-and-out affirmation of the right to discriminate against white students (and sometimes Asians) in the name of “diversity.” David Hinojosa of MALDEF (Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund) got it right when he said, “It’s a great decision by the court reaffirming diversity as a compelling interest.”

If even this allegedly “conservative” Supreme Court is not willing to ban racial discrimination against whites, it is hard to imagine any future Supreme Court that will. The most recently appointed justice, Elena Kagen, did not take part in the decision because she argued for discrimination against whites when she was solicitor general, and it is impossible to imagine any justice appointed by a Democrat — and what other kind are we likely to get? — voting to strike down “affirmative action.” This could be the high-water mark for the Supreme Court’s partial and inadequate rollback of the race-preferences policies under which whites have suffered for the last 40 years.

The court piously denounced racial “quotas,” and reaffirmed that discrimination must be “narrowly tailored” to achieve its goals, and may be resorted to only when non-racial tricks to achieve racial diversity don’t work. This is all the loophole a racial zealot needs. That is why UT President William Powers said he was “encouraged” by the ruling, and notes that it won’t effect admissions policies at all.

So what actually happened?

UT has used every trick it could think of to get more blacks and Hispanics into its flagship campus at Austin. At first, it didn’t even need tricks. It openly gave non-whites extra consideration, which meant they got in with much worse grades and test scores than whites. However, in the 1996 case of Hopwood v. Texas the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that this was a violation of the “equal protection” clause of the 14th Amendment, and said UT must not pay any attention to race.

UT immediately started paying attention to other things. It invented something called a “Personal Achievement Index” (PAI) that gave applicants extra credit for being poor, growing up without a father, and speaking a language other than English at home — but no points for race. It was a transparent effort to get race in through the back door, but it didn’t work very well. An annoying number of white students got high PAI scores.

So, in 1997, the Texas legislature obligingly passed a law saying that any Texas student who graduated in the top 10 percent of his high school class would be admitted to UT. This was another allegedly non-racial way to be gin up diversity that was based on the fact that so many Texas high schools are largely segregated.

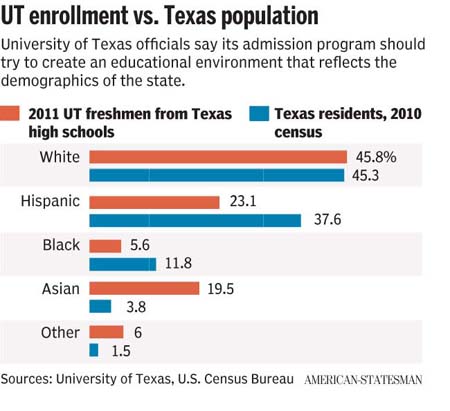

All this maneuvering worked. Before Hopwood, when UT was free to discriminate however it liked, the entering class was, on average, 4.1 percent black and 14.5 percent Hispanic. After it invented the PAI system and got the 10-percent law passed, those figures increased to 4.5 percent and 16.9 percent.

But the new system had drawbacks. Some of those top-10-percenters were doubtful characters from miserable ghetto high schools, and although they were certifiably diverse, not even the anti-white fanatics thought they belonged at UT. So in 2003, when the Supreme Court ruled in the two Grutter cases that race could be part of the admissions process after all (see my analysis of those tortured cases here), UT shouted for joy and went back to racial discrimination.

UT set aside 25 percent of its incoming class for people who were not in the top 10 percent, not poor or illegitimate, etc., but whom it could let it for various slippery reasons, mainly race. And now that it could go back to explicit racial preferences, it cut back automatic admits to the top eight percent of students. UT admits that it wanted middle-class, non-deprived blacks and Hispanics who may not have been at the tops of their classes, but who attended good schools and were better than the nasty types coming from the worst schools. UT was worried these lowlifes might encourage “stereotyping.” It was this part of the admissions process — that openly considers race — that Abigail Fisher challenged.

So, what did the court decide? The worst part of its ruling was to confirm, seven-to-one (as noted above Elena Kagan sat out this decision, but we know very well what she thinks), that “student body diversity is a compelling state interest that can justify the use of race in university admissions.” That is the heart, soul, lungs, and gizzard of the ruling.

A university, said the court, is in the business of educating people, and if a university decides in its Olympian wisdom that “diversity” is an important part of an education, the university must be shown “deference.” If UT thinks having non-whites on campus is vital to a college education, then, yes, it may can kick Abigail Fisher and other white applicants in the teeth. However, it can’t do it according to rules ordinary people would understand.

UT can’t just simply add 200 points to SAT scores as a reward for being black. It can’t just hold open 20 percent of the slots for Mexicans. That would be something people understand, and white applicants would know what they were up against. Instead, discrimination has to be “narrowly tailored,” and therefore “cannot use a quota system.” It must “remain flexible enough to ensure that each applicant is evaluated as an individual and not in a way that makes an applicant’s race or ethnicity the defining feature of his or her application.” Simple rules are unconstitutional. A university must meditate and consult chicken entrails and take it to the Lord in prayer before it slams the door on better qualified whites and Asians.

So what’s all this about sending the case back to the lower courts? The problem with the Appeals Court ruling that upheld the admissions policy, say the justices, is that it did not paw through the chicken entrails. Discrimination is fine and we don’t dispute that, they say, but the Appeals Court should have plumbed the mysteries of the process to see whether it was “narrowly tailored.” The only thing the Appeals Court considered was whether UT reintroduced race-based admissions “in good faith.” That, say the justices, is not a strict enough hurdle:

On this point, the University receives no deference. Grutter made clear that it is for the courts, not for university administrators, to ensure that ‘[t]he means chosen to accomplish the [government’s] asserted purpose must be specifically and narrowly framed to accomplish that purpose.’

Grutter, the justices added, also “imposes on the university the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available, workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice.” Since the District Court and the Appeals Court both skated over those questions, the case goes back to the Appeals Court for another round. In the meantime, UT’s admissions policy is unchanged.

I repeat: This not a compromise, or if it is a compromise it gives very little to the foes of affirmative action. Courts may be able to look a little more closely at how universities go about achieving diversity. For the most part, however, this is a reaffirmation of Sandra Day O’Connor’s boneheaded decision of 10 years ago that upholds the principle of racial discrimination against whites and surrounds it with a fog of mumbo-jumbo about “narrow tailoring.” Also, this ruling applies directly to only one admissions policy: that of the University of Texas at Austin. Even if the lower courts find that there was too much mumbo and not enough jumbo, it will make no difference to other admissions policies. Each one will have to be litigated separately. There are plenty of liberal judges who will bless even blatant discrimination, so long as it is against whites.

And I repeat again: For the foreseeable future, we are not likely to get a court that is more hostile to “affirmative action” than this one. If the Roberts Court won’t overturn the principle of racial preferences, the increasingly non-white court we can expect in the future certainly will not.

In her dissent, Justice Ginsberg pointed the way. She noted that the 10-percent deal in Texas was a transparent dodge to get non-whites on campus. If that’s OK, she wanted to know, what’s wrong with plain old racial preferences. We need them, she said, because of “the lingering effects of an overtly discriminatory past” and “the legacy of centuries of law-sanctioned inequality.” Quoting herself in a previous dissent, she wrote: “Among constitutionally permissible options, I remain convinced, ‘those that candidly disclose their consideration of race [are] preferable to those that conceal it.’ ” She is all for race preferences for non-whites; lay ’em on thick. She said the UT admissions policy was plenty “narrowly tailored,” and said if it were up to her she would let the university get on with it.

Where were the court’s conservatives, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas? Justice Scalia put his head in hole, saying that Miss Fisher did not ask that the principle of discrimination be considered, so he was happy to send the case back to have the entrails examined. Theoretically that is true. During oral argument Miss Fisher’s lawyers danced away from asking for a reexamination of principle, and said they would be satisfied with a ruling on whether UT’s admissions policy was sufficiently incomprehensible.

Justice Scalia despises racial preferences, yet he has just put his name on a decision that confirms them in principle. Maybe he sees a better chance ahead to knock them dead, but if he does, he must have X-ray vision.

Clarence Thomas, the only black on the court, was the only justice to take a principled stand against preferences across the board. In a dissent that the media are sure to ignore, he analyzed what is really meant by the term “compelling state interest,” which the University of Texas has invoked to justify discrimination. He wrote that official government racial discrimination is so loathsome that whatever it achieves had better be awfully important: “[O]nly those measures the State must take to provide a bulwark against anarchy, or to prevent violence, will constitute a ‘pressing public necessity’,” adding that “the educational benefits flowing from student body diversity — assuming they exist — hardly qualify as a compelling state interest.”

Justice Thomas went on to make interesting comparisons between the arguments segregationists used to make and the arguments the preferences crowd are now making. Segregationists used to say that blacks need separate schools because blacks are happier among their own kind, and black schools give them a chance to be leaders on campus. The preferences maniacs say “diversity” will break down “negative stereotypes” and help people become leaders in our increasingly multi-culti country.

Justice Thomas wrote:

There is no principled distinction between the University’s assertion that diversity yields educational benefits and the segregationists’ assertion that segregation yielded those same benefits. . . . The Constitution does not pander to faddish theories about whether race mixing is in the public interest. The Equal Protection Clause strips States of all authority to use race as a factor in providing education.

He also pointed out that the racial angle is blindingly obvious in UT’s admissions gimmickry. The students who were let in outside the top-ten-percent had the following average SAT scores: blacks — 1524, Hispanics — 1794, whites — 1914, and Asians — 1991. That’s a nearly 400-point difference between blacks and whites. Please recall that the Supreme Court says that when preferences are used, they are not supposed to make “an applicant’s race or ethnicity the defining feature of his or her application.” UT had to ignore that language to get spreads like that. Justice Thomas wrote that if it were up to him, he would ban race preferences forever.

So, what happens now with Fisher v. University of Texas? It was a fellow named Edward Blum, who runs a one-man show called the Project on Fair Representation that brought Abigail Fisher and her lawyers together and made the case happen. Now he has to go back to the Appeals Court and arrange a rematch. He says he will do so, but eventually he will run out of money. The University of Texas can dip into the state treasury and litigate the case into the next century.

The astonishing irony in this case, as in so many others, is that the one black justice is the only one who opposes any kind of government discrimination for whatever reason. All the whites are on record as saying discrimination is fine, so long as it is sufficiently opaque. Of course, it is only in this insane, topsy-turvy world that Justice Thomas sounds like a hero. In a properly race-conscious world, organizations and individuals would discriminate freely, entirely as they saw fit.

Far-seeing whites should think carefully about arguments against discrimination in principle because discrimination, private and even public, is necessary to our survival as a people. In cases such as Fisher, we are drawn to anti-discrimination arguments because the only acceptable, legal targets of public discrimination are ourselves. Such is the astonishing, absurd, and suicidal fix we whites have gotten ourselves into while we are still, for the time being, the majority.

The full text of the Supreme Court’s decision is here.