What Is the West Guilty Of?

Roland Johnson, American Renaissance, October 18, 2013

According to the trendy nonsense of our time, the history of Europe and Western Civilization is a legacy of shame. The West bears the mark of Cain for its sins of aggression, colonialism, slavery, and racism. It does not matter that the West gave birth to the ideals of liberty and human dignity — and practiced those ideals by eliminating the slave trade and colonial rule. Or that our political systems have promoted freedom around the world, and our science has improved the lives of people everywhere.

For a sense of balance, let us consider the history of non-Western aggression against the West. The fact that so many of us are unaware of these aggressions is proof of the bias of our media and educational systems.

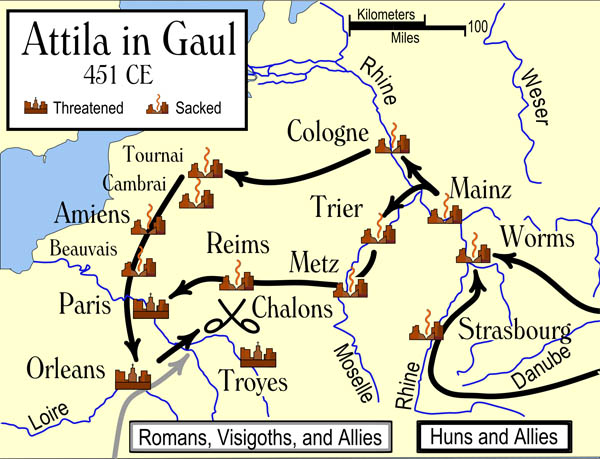

A good place to start is the invasion of Europe by Central-Asian Huns in the fourth and fifth centuries. This fierce warrior people launched a series of aggressive attacks against Germanic tribes living in what is now Russia and Eastern Europe. Fleeing pillage and slavery, many Germans sought sanctuary in the Roman Empire, but the Huns kept advancing into Roman territory. Finally, in 451, a combined Roman and Germanic army drove Attila’s armies back at the Battle of Châlons (near Châlons-en-Champagne in modern-day France).

Alas, that victory did not save Rome. The movement of the Germanic tribes into the Western Empire destabilized and overwhelmed it. What followed was a Dark Age during which Europeans languished for centuries. Part of the blame rests with the Huns.

Scarcely had Europe emerged from the Dark Age when it faced another Asiatic invasion. This was the onslaught of the Mongols who turned west in the 13th century after conquering large parts of Asia. They pillaged Russia and Eastern Europe, leaving behind devastation and slavery. This is an account written by Giovanni de Plano Carpini, the Pope’s envoy to the Mongol Great Khan, who traveled through Kiev in February 1246:

They [the Mongols] attacked Rus [Russia], where they made great havoc, destroying cities and fortresses and slaughtering men, and they lay siege to Kiev, the capital of Rus; after they had besieged the city for a long time, they took it and put the inhabitants to death. When we were journeying through the land we came across countless skulls and bones of dead men lying on the ground. Kiev had been a very large and thickly populated town, but now it has been reduced almost to nothing, for there are at the present time scarce two hundred houses there, and the inhabitants are kept in complete slavery.1

The Mongols wanted all of Europe, and might have gotten it if the death of the great Ogedei Khan in 1242 had not sent Batu Khan, the leader who was ravaging Europe, back to the Mongolian capital to ensure his succession. Batu Khan left Eastern Europe depopulated and in ruins, but his return to Ulan Bator saved Western Europe. Still, Mongols remained in southern and central Russia for centuries in the Crimean, Kazan, and Astrakhan Khanates, which became hubs for slave raiding and trading. Some historians estimate that they enslaved more than three million Ukranians, Russians, and Poles.2 The word “slave” is etymologically close to the word “Slav” because of the number of Slavs who were enslaved over the centuries.

Although the heart of Europe was spared, the Mongols may have inflicted an even more horrible toll. In 1347, as bubonic plague raged from central Asia to the edges of their empire, Mongol forces besieged a Genoese outpost in the Crimea. They catapulted infected corpses into the city, thereby infecting Genoese traders who later traveled to southern Europe. The plague broke out in those areas and spread across the continent. Between 1348 and 1350, bubonic plague — the Black Death — wiped out a third or more of Europe’s population.3

The predations of the Huns and Mongols, however, were short-lived, compared with the thousand years of aggression unleashed against Europe by Moors, Turks, and other Muslims. A mere century after its founding, Islam advanced by the sword across the Middle East and North Africa and stood at the gates of Spain in 711.

Muslims quickly conquered most of that country and then surged into France. The fate of Europe hung in the balance at the Battle of Tours in 732, when the forces of Charles Martel defeated the Muslims and drove them back into Spain. The war in Iberia between Islam and Christendom waxed and waned for seven more centuries. Spanish Christians under Muslim rule lived in varying conditions at different times, but always had the status of dhimmis: non-Muslims subject to discriminatory laws.

Bataille de Poitiers en octobre 732 by Charles de Steuben (1837). A triumphant Charles Martel (mounted) facing Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi (right) at the Battle of Tours.

Spaniards managed to gain back some of their territory, but in 1085 the Muslim commander Yusef ibn Tashufin led a fierce African army in an attempt to reconquer all of Spain. Mayhem and slavery followed in his wake, and he was stopped only by the courage of the legendary El Cid and other Spanish warriors. In the next century, another African army tried to finish what Yusef started. Brutal warfare continued until the Spaniards decisively defeated the Muslims at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212. Nevertheless, Islam maintained an outpost in Europe until the Spaniards overran the last Muslim stronghold, Grenada, in 1492.

Many Muslims who left settled in North Africa. Some of them took to slave raiding along the coasts of Europe. In his book Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800, Professor Robert Davis noted that between those dates, “Enslavement was a very real possibility for anyone who traveled in the Mediterranean, or who lived along the shores in places like Italy, Spain and Portugal, even as far north as England and Iceland.” During that time, which was approximately the same period as Atlantic slave trade, Davis estimates that Muslim slavers captured one to one-and-a-quarter million Europeans, often working them to death in quarries and oarsmen in galleys.4 This number well exceeds the 800,000 black slaves estimated to have been taken to North America.

After the victory of Las Navas de Tolosa and the retreat of the Mongols, the heartland of Europe enjoyed only a brief period of peace. In the middle of the 13th century a new force gathered under the flag of Islam: the Ottoman Turks. Originally from Central Asia, the Ottomans drove into southeastern Europe in the early 14th century. In 1389 they crushed the Serbs at the battle of Kosovo and continued north for the next century-and-a-half. Europe’s defenders finally managed to halt them at the gates of Vienna only in 1529.

The Turks were renowned for their cruelty. During their rule of southeastern and central Europe they enslaved millions of people — three million from Hungary alone — sending many to the slave markets of Asia Minor and the Middle East. Some of the women went to harems; some of the men were made eunuchs. In Eastern Europe, as in Spain, Christians were dhimmis, and were forced to offer a regular quota of their sons to serve in the Ottoman army’s Janissary corps. These men had to embrace Islam and cut all ties to their families.5

The threat to Europe subsided somewhat in the 16th century, following two stunning Christian victories. The first was in 1565 when the Turks attacked Europe’s western flank by trying to capture the island of Malta. The heroic defenders — Spaniards, Italians, Maltese, outnumbered eight to one — hurled the Turks back with heavy losses, in what was one of the most bloody and bitterly contested sieges in history.

The second victory was at Lepanto, off the coast of Greece in 1571, when Christians met a Turkish armada of galleys intent on destroying Christian naval power once and for all. The Turks were stopped by the Holy League fleet, largely manned by Spaniards and Venetians and commanded by Don John of Austria. Shortly before the battle, the Europeans learned that the Turks had captured Cyprus, cut off the ears and nose of the Christian commander, and flayed him alive. Don John’s men vowed vengeance — which they took abundantly. Most of the Turkish fleet was either destroyed or captured. Don John’s men liberated 15,000 European slaves who had been Turkish galley slaves.6

The Turkish threat subsided but did not disappear. In 1683, the Ottomans launched their final attempt to conquer Europe, advancing once again to the gates of Vienna, where they lay siege to the city. Coming to its rescue was a Polish-German force commanded by King Jan Sobieski of Poland. The Ottoman army outnumbered Sobieski’s, but the Polish king launched a surprise attack that routed the invaders.

For approximately two more centuries, the Ottomans fought a losing battle to keep their European possessions. They could not keep up with European military technology, and by the dawn of the 20th century, Europeans had long forgotten their fear of Muslim conquest. That danger was over — or so it seemed.

Long before the Muslim collapse, the nations of Europe began to establish their own colonies. Some, like the Spanish conquests in the New World, were harshly run, but centuries of Islamic aggression forged the Spanish character. In any case, European colonialism rarely lasted much more than two centuries, a short span compared to the foreign domination of large portions of Europe. European rule often ended peacefully, unlike the alien rule of Europe, which had to be thrown off by force of arms.

Europeans conducted their own slave trade, but they also did more than any other people to end slavery. Africans who made fortunes selling tribal enemies as slaves bitterly resisted the abolition of the trade, and slavery has still not been eradicated in Africa. In modern times, the West has given enormous amounts of aid to the Third World.

Why hate the West?

Why do so many Westerners hate the West? The roots of their thinking go back to classical Marxism, which aimed to incite working class rebellion. The workers refused to rebel, however, and sided with their national governments during World War I. After the war, a number of Marxists decided to revise their dogma. Prominent among them was a group living in Frankfurt, Germany, known as the Frankfurt School, who believed that class struggle was not enough to bring about revolution. What was necessary was cultural Marxism that would attack the key pillars of Western Civilization: religion, patriotism, and family life. They called this attack on Western identity and culture “critical theory,” and members of the Frankfurt School brought this theory to the United States.7

Critical theorists Max Horkheimer (front left), Theodor Adorno (front right), and Jürgen Habermas (back right).

Today, critical theory holds tremendous power. It endlessly harps on the West’s colonial past without mentioning the colonization of the West. It holds up Hitler and the Third Reich as symbols of Europe, without conceding that most of the West united against Hitler.

In Europe, cultural Marxists are using Muslim immigration to destroy the West claiming, ironically, that Europeans must atone for their sins by surrendering to those who sinned against them for so long. In America, Latin American immigration serves the same purpose. Cultural Marxists use Western guilt, manipulated by critical theory, to neutralize opposition — and yet these ideological heirs to the Cheka dungeons, the Ukrainian famine, the Gulag camps, and the Cambodian genocide have no moral authority to condemn the West

Today the fate of our civilization is in the balance, just as much as it was at Tours and Vienna. If they are to have a future, Europe and its overseas outposts must revisit their past. They must shed their guilt and rekindle their will to live. The spirits of Charles Martel, El Cid, Jan Sobieski, and all their valiant company will point the way.

_________________________________________

1. Wikipedia: Mongol Conquests-Europe. Original source.

2. Mike Bennighof Ph.D. Soldier Khan, September 2007, www.avalance.com.

3. The New Encyclopedia Britannica, Vol 2, 15th edition p. 253.

4. Davis, Robert Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary coast, and Italy, 1500-1800 P.23, Palgrove MacMillan, 2003.

5. Fregosi, Paul. Jihad, P.328, Prometheus Books 1998.

6. Ibid., P.328.

7. William Lind, the Origins of Political Correctness, Accuracy in Academia (www.academia.org), February 5, 2000.