Anthony Trollope’s White Genius

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, May 25, 2012

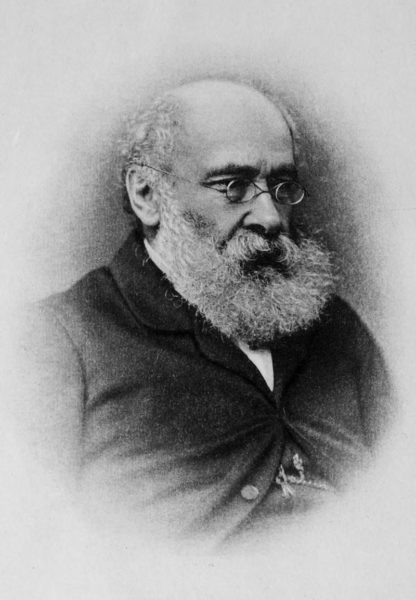

Anthony Trollope

It is hard to think of behavior that is genuinely exclusive to one race. Naming one’s daughter Quaneesha or leaving one’s estate to the Sons of Confederate Veterans are as close as anything I can think of, but there are others that are not far off: having 30 children by 11 women, volunteering for the Red Cross, or living under a bridge after a career with the NFL. Certain things just seem quintessential.

It occurred to me, as I read the last few pages of Barchester Towers, that a taste for Anthony Trollope is something else that sends an almost unerring racial signal. You could add “reads Trollope” to the profile of people you would like to meet through a dating service, and you wouldn’t have to specify race. If Detroit still has public libraries, I bet the Trollope volumes never leave the shelves.

Trollope is one of my favorite authors — I have read a dozen of his novels — but probably even in the eyes of most whites he has little to recommend him. In Barchester Towers, which I just finished, there is no sex. There is no violence — with the exception of a lady who boxes the ear of a man who forgets himself so far as to put his arm around her waist. There are no car chases — cars had not been invented — no shipwrecks, no abductions, no mistaken identities, no great matters of state, in fact, nothing that would make for excitement by contemporary standards.

Barchester Towers is a story of 19th-century church politics, set in the fictional British cathedral town of Barchester. Most of the characters are curates, chaplains, archdeacons, bishops, minor canons, deans, prebendaries, and their families. I don’t know how it would be possible to make a novel sound more boring. But Trollope was a genius, who filled his stories with finely drawn personalities whose passions and follies and triumphs and weaknesses are as vivid as anything in literature. Within the unpromising limits of rural England, he invents high drama that is all the more compelling because his characters are so ordinary. He sometimes gets his characters into improbable fixes, but this only gives him a greater range of emotions to depict. To read one of his novels is to take a tour of the human mind, with one of the English language’s great stylists as your guide.

Trollope wrote in sentences that are sometimes long but always well crafted. He makes classical allusions. He expects his readers to enjoy language as much as he does, and to be unafraid of antique and unusual turns of phrase. In other words, people who are forced to read him before they are old enough to understand him hate him just as they hate Shakespeare or Dickens, but for those who discover him when they are ready, he is pure joy.

I skimped in my description of Barchester Towers. It is about church politics, but it is also about love. With few exceptions, Trollope’s novels follow at least one couple to the point of a declaration, but there are always snags, and the lady is as likely to spurn her suiter as she is to accept him.

I don’t know why reviewers of novels so seldom let the novel speak for itself, but Barchester Towers is worth quoting almost at random. Here is the state of mind of a 40-year-old prelate, who has become acquainted with an agreeable young widow:

He had, as was his wont, asked himself a great many questions, and given himself a great many answers; and the upshot of this was that he had set himself down for an ass. He had determined that he was much too old and much too rusty to commence the manoeuvres of love-making; that he had let the time slip through his hands which should have been used for such purposes; and that now he must lie on his bed as he had made it. Then he asked himself whether in truth he did love this woman; and he answered himself, not without a long struggle, but at least honestly, that he certainly did love her. . . He also decided that Eleanor did not care a straw for him. Then he made up his mind not to think of her any more, and went on thinking of her till he was almost in a state to drown himself in the little brook which ran at the bottom of the archdeacon’s grounds.

And here is the redoubtable Signora Neroni, ravishingly beautiful, but a married woman and a cripple who must spend her life on a couch. She fascinates all men who meet her, including the unfortunate Mr. Slope:

As for the signora . . . she cared no more for Mr Slope than she did for twenty others who had been at her feet before him. She willingly, nay greedily, accepted his homage. He was the finest fly that Barchester had hitherto afforded to her web; and the signora was a powerful spider that made wondrous webs, and could in no way live without catching flies. Her taste in this respect was abominable, for she had no use for the victims when caught. She could not eat them matrimonially as young lady-flies do whose webs are most frequently of their mother’s weaving. Nor could she devour them by any escapade of a less legitimate description. Her unfortunate affliction precluded her from all hope of levanting with a lover. It would be impossible to run away with a lady who required three servants to move her from a sofa. . . .

Mr. Slope was madly in love, but hardly knew it. The signora spitted him, as a boy does a cockchafer on a cork, that she might enjoy the energetic agony of his gyrations. And she knew very well what she was doing.

Needless to say, ladies do not like the signora, and Mrs. Proudie, the bishop’s wife, does not even leaven her feelings with any hope of reform:

Her dislike of Signora Neroni was too deep to admit of her even hoping that that lady should see the error of her ways. Mrs. Proudie looked on the signora as one of the lost, — one of those beyond the reach of Christian charity, and was therefore able to enjoy the luxury of hating her, without the drawback of wishing her eventually well out of her sins.

Sentences like these were not written for speed reading, but they are full of entertainment for those who take the time to find it. Some people like this kind of writing and some don’t. Some people like opera and some don’t. But I think it is hard to like Anthony Trollope and not be white.

This is hardly unique to Trollope, of course. All the great authors of Western literature — and some critics do not even rank Trollope among the really great — have the same subtle understanding of human nature and make the same demands on readers. They appeal to a sensibility that is not only thoroughly adult, but adult in a way that is thoroughly European. I suppose there must be a few Frenchified Senegalese who read Stendahl for pleasure, but it takes an effort of the imagination to conjure one up.

And this, of course, is one of the reasons why curricula are changing. Hispanics and blacks do not see the point of reading Tolstoy or studying Italian, and as their share of the population increases, colleges and high schools will give up trying to get even whites to do these things. And some unfortunate whites who have been taught to think that Alice Walker and Rigoberta Menchu are great writers will never discover what great writing really is.

I am not saying that you have to read Antony Trollope to be genuinely white; far from it. But those who have not read yet him have in store an experience that is, I believe, quintessentially white.