Black Kids Go Missing at a Higher Rate Than White Kids. Here’s Why We Don’t Hear About Them

Harmeet Kaur, CNN, November 3, 2019

{snip}

In fact, data shows that missing white children receive far more media coverage than missing black and brown children, despite higher rates of missing children among communities of color.

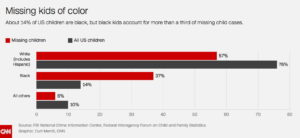

The FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database lists 424,066 missing children under 18 in 2018, the most recent year for which data is available. About 37 percent of those children are black, even though black children only make up about 14 percent of all children in the United States.

It’s harder to say how many Hispanic kids are missing. The FBI’s report groups white and Hispanic children together. Based on other reports, about 20 percent of missing children are Hispanic or Latino, according to Robert Lowery, vice president of the missing child division at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). But the real number, he said, is likely higher.

{snip}

Here are some reasons experts say we don’t hear more about missing children of color:

Their families are hesitant to call police

Some families are hesitant to contact law enforcement, even if they think their child is missing.

“There’s a sense of distrust between law enforcement and the minority community,” said Natalie Wilson, co-founder of the Black and Missing Foundation.

{snip}

Other families might not report that their child is missing because they fear it could have unintended, negative consequences.

{snip}

They don’t get as much media coverage

{snip}

A 2010 study found that black children were significantly underrepresented in TV news. Even though about a third of all missing children in the FBI’s database were black, they only made up about 20 percent of the missing children cases covered in the news.

A 2015 study was bleaker: though black children accounted for about 35% of missing children cases in the FBI’s database, they amounted to only 7% of media references.

{snip}

Families don’t have the resources

Families don’t always have the financial resources to respond appropriately when their child is missing. They might not be able to afford a private investigator or take off from work to help look for their child and follow up with law enforcement and the media.

And in some cases, they may not know what to do.

Wilson said some people are under the misconception that they must wait 48 hours before filing a police report, when that waiting period varies by location. Places like Illinois or Washington, DC, don’t have waiting periods to report a child missing.

{snip}

The Black and Missing Foundation helps families of color file police reports, create missing posters and spread the word about missing children.

{snip}

Some get classified as runaways

{snip} But missing children can refer to kids who are abducted by relatives or children who leave home, either voluntarily or after being lured by someone else.

Many missing children of color are classified as runaways, Wilson said. And while running away from home isn’t a problem unique to nonwhite children, they are particularly vulnerable.

A significant number of nonwhite children who go missing are either homeless or in foster care, said Wilson, and many are at risk for sex trafficking. Data shows black children are overrepresented in foster care and are at a much higher risk for homelessness.

Law enforcement often classify children of color as runaways without having all the details, Wilson said. Because those kids are considered to have voluntarily left home, Amber alerts aren’t sent out about them and they typically aren’t covered in the news.

{snip}

The NCMEC no longer distinguishes between runaways and abductions on their posters of missing children.

{snip}

Sometimes, children of color get classified as runaways when they are truly missing. {snip}

{snip}