Everything You Don’t Know About Mass Incarceration

Rafael A. Mangual, City Journal, Summer 2019

{snip}

{snip} But all the Democrats are striking the same chord. “More people [are] locked up for low-level offenses on marijuana than for all violent crimes in this country,” Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren, another top-tier Biden challenger, declared at last year’s We the People Summit. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator known best for his left-wing economic populism, has described felon disenfranchisement as racist voter suppression. And South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg told Out that incarceration is “clearly worsening some of the patterns of racial inequality in our country.”

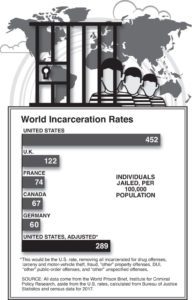

Eight of the declared candidates contributed to a recent compendium published by the Brennan Center for Justice, titled Ending Mass Incarceration. The essays provide a useful summation of Democratic talking points on criminal justice. That the United States over-incarcerates is evidenced, reformers say, by the numbers: though it has about 5 percent of the global population, the U.S. houses about a quarter of the prisoners worldwide. America’s high incarceration rate, goes another assertion, is driven by the unjust enforcement of “low-level” and “nonviolent” offenses, particularly drug crimes. A further charge: the system is racist, given how much more likely blacks are to be behind bars compared with whites. Finally, they say that sentences have gotten way too long.

{snip} But none of the above claims advanced by the presidential hopefuls is correct — and acting on any of them would be disastrous.

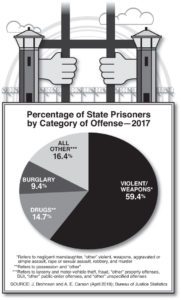

{snip} Those incarcerated primarily for drug offenses constitute less than 15 percent of state prisoners. Four times as many state inmates are behind bars for one of five very serious crimes: murder (14.2 percent), rape or sexual assault (12.8 percent), robbery (13.1 percent), aggravated or simple assault (10.5 percent), and burglary (9.4 percent). The terms served for state prisoners incarcerated primarily on drug charges typically aren’t that long, either. One in five state drug offenders serves less than six months in prison, and nearly half (45 percent) of drug offenders serve less than one year.

That a prisoner is categorized as a drug offender, moreover, does not mean that he is nonviolent or otherwise law-abiding. Most criminal cases are disposed of through plea bargains, and, given that charges often get downgraded or dropped as part of plea negotiations, an inmate’s conviction record will usually understate the crimes he committed. The claim that drug offenders are nonviolent and pose zero threat to the public if they’re put back on the street is also undermined by a striking fact: more than three-quarters of released drug offenders are rearrested for a nondrug crime. It’s worth noting that Baltimore police identified 118 homicide suspects in 2017, and 70 percent had been previously arrested on drug charges.

Not only are most prisoners doing time for serious, often violent, offenses; they’ve usually received (and blown) the second chance that so many reformers say they deserve. Justice Department studies from 2000 through 2009 reveal that only about 40 percent of state felony convictions result in a prison sentence. A Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) study of violent felons convicted over a 12-year period in America’s 75 largest counties shows that 56 percent of the offenders had a prior conviction record.

Even though most state prisoners are serious and serial offenders, nearly 40 percent of inmates serve less than a year in prison, with the median time served about 16 months. {snip} In his book Locked In, John Pfaff — a leader in the decarceration movement — plotted state prison admissions and releases from 1978 through 2014 on a graph. If sentence lengths had increased, the two lines would diverge as admissions outpaced releases; in fact, the lines are almost identical.

{snip} The #cut50 initiative, founded by activist and CNN host Van Jones, aims to halve the prison population. Scholars at the Brennan Center have called for an immediate 40 percent reduction in the number of inmates.

{snip}

{snip} Though the decarceration crowd continues to point to racial disparities in criminal enforcement, the data on criminal victimization suggest that the burden of any crime increase that accompanied large-scale prisoner releases would mostly fall on low-income black communities. Though black men constitute about 7 percent of the population, they accounted for 45 percent of America’s 15,129 homicide victims in 2017, FBI numbers show. A BJS study of homicides committed from 1980 to 2008 found that the victimization rate of blacks was six times that of whites. The black homicide-offending rate was about eight times the white rate. These differences, not racial animus, go a long way toward explaining the oft-lamented fact that black men are six times likelier to be incarcerated than white males.

{snip} A January 2017 University of Chicago Crime Lab study found that, of those arrested for homicides or shootings in Chicago in 2015 and 2016, about “90 percent had at least one prior arrest, approximately 50 percent had a prior arrest for a violent crime specifically, and almost 40 percent had a prior gun arrest.” On average, someone arrested for a homicide or shooting had nearly 12 prior arrests, the study noted — and almost 20 percent had more than 20 priors. You find more of the same in crime-wracked Baltimore. According to the Baltimore Sun, “85 percent of the 118 murder suspects identified by police [in 2017] had prior criminal records,” with nearly 36 percent being “on parole or probation” at the time of the alleged crime.

The serial offender isn’t just a problem in the highest-crime American cities. Data show that such crime has been occurring in urban jurisdictions across the country for years. The BJS study on violent felons convicted in large counties found that offenders on probation, parole, or released pending disposition of a case constituted 37 percent of those convicted during the 12-year period examined. With so many of the nation’s most serious crimes perpetrated by people with an active criminal-justice status — and with 83 percent of released prisoners arrested for a new crime within nine years of getting out — the safety benefits of incapacitation become startlingly clear.

Large-scale decarceration would also undermine the criminal-justice system’s retributive function, one of the four penological justifications for incarceration (with rehabilitation and deterrence joining incapacitation to constitute the other three). {snip}

Small wonder that recent polling shows little support for decarceration. A 2016 Morning Consult /Vox poll found that 65 percent of respondents somewhat or strongly opposed “reducing sentences for crimes in general,” versus just 24 percent supporting such measures. The same poll reported only 32 percent of respondents strongly or somewhat supporting reduced sentences for nonviolent offenders likely to re-offend, and the support was lower still for easing sentences for violent criminals both likely and unlikely to commit further crimes.

America’s incarceration numbers would be even higher if more perpetrators of serious crime were apprehended. Most of the crimes that so many Americans believe — with good reason — should result in time behind bars go unanswered. Either the crimes aren’t reported or police prove unable to close the cases.

The FBI tracks and reports on eight “index crimes” committed in the United States. Half of those offenses are violent, and half concern property: murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny theft, motor-vehicle theft, and arson. Since 2010, the U.S. has averaged about 1.2 million violent index crimes and 8.5 million property index crimes yearly. Keeping in mind that many similar crimes never get reported to the FBI, note that police clear just 46.8 percent and 18.9 percent of violent and property index offenses, respectively. Put differently, since 2010, about 5.1 million violent index crimes and 54.9 million property index crimes have gone unpunished — which works out to more than 7.5 million of these offenses yearly. Even assuming that certain criminals commit a disproportionate number of the crimes, one can say with confidence that, in any given year, a large number of people who should be in prison are not.

The U.S. incarcerates more people than any other nation, but international comparisons ignore important differences between other countries and ours. For instance, as is often pointed out by the same Democrats when discussing gun control, the U.S. has significantly higher murder and violent-crime rates than many other developed nations, and those rates of serious crime drive much of the disparity in incarceration — not low-level and nonviolent drug offenses. Likewise, the racial disparities in our prison population are a function of racial disparities in serious criminal offending, not systemic bias. Contrary to the decarceration narrative, most of those imprisoned in America are highly likely to reoffend; most prisoners have committed just the kinds of serious violations that most Americans agree should put them away; and plenty of criminals already walk our streets today who committed their crimes without detection, were released from prison or jail sooner than they should have been, or received too-light sentences, given the level of their actual infractions.

{snip}