Ronald Reagan and the Fight Against Racial Preferences

Robert Detlefsen, American Renaissance, June 1999

The Reagan Presidency and the Politics of Race: In Pursuit of Colorblind Justice and Limited Government, by Nicholas Laham, Praeger Publishers, 1998, 240 pp.

Few public issues have been the subject of as much study and debate as that which for the last thirty years has gone by the name of “affirmative action.” And yet it is indicative of just how futile this exercise has been that today there is still no general agreement as to what the term even means — witness, for example, the tendency of many conservatives to speak forcefully against racial “quotas” and “preferences” while still supporting “affirmative action.” Florida Governor Jeb Bush recently dismissed anti-preference crusader Ward Connerly by insisting that affirmative-action efforts in his state in no way discriminate against whites. When Mr. Connerly offered proof to the contrary, Gov. Bush accused him of trying to “start a war.”

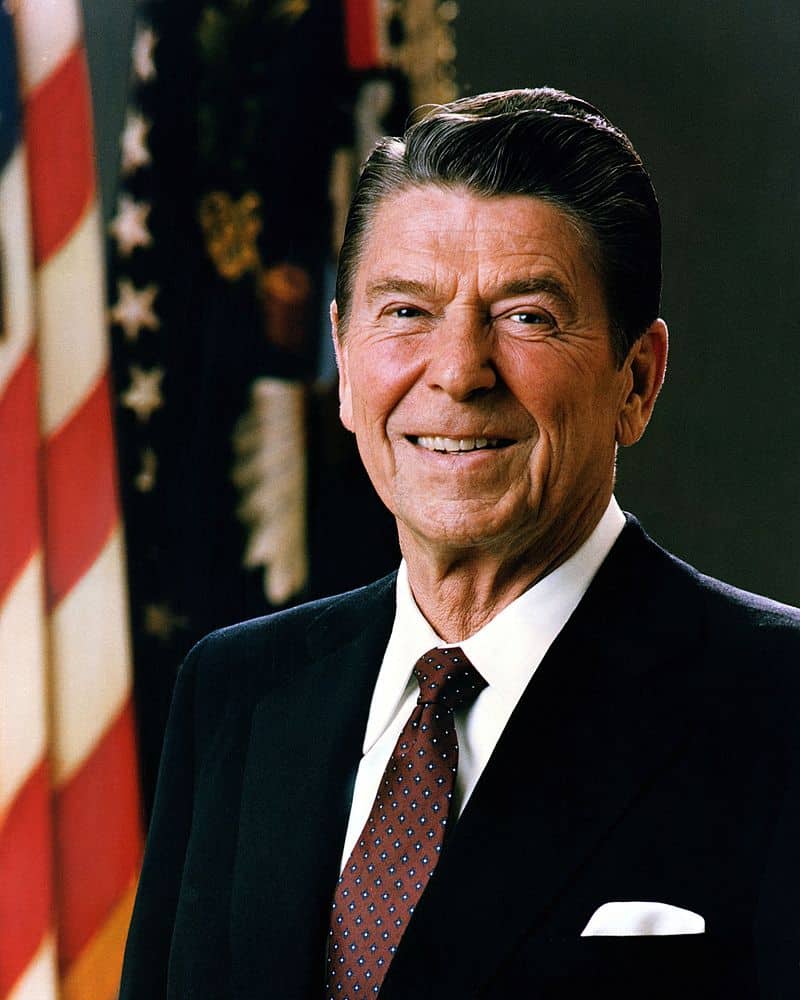

Ronald Reagan

All of which shows that public discussion of affirmative action is no more elevated today than it was in 1981 when Ronald Reagan became the first president to criticize the slide of civil rights policy into mandatory discrimination in favor of government-designated minorities. As Nicholas Laham reminds us in The Reagan Presidency and the Politics of Race, Pres. Reagan was castigated by liberal elites for supposedly practicing “the politics of racial division” in order to attract the votes of working-class whites — the so-called Reagan Democrats — who thought affirmative action was a “threat to their socioeconomic position.” Mr. Laham sets out to absolve Pres. Reagan of this charge, but his strategy for doing so is baffling.

The problem is that, despite acknowledging that the affirmative-action policies that Pres. Reagan inherited frequently entailed direct, intentional discrimination against whites, Mr. Laham does not seem to grasp that because of this, affirmative action was itself at odds with federal civil rights laws — especially the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which forbade racial discrimination. What is more, the civil rights movement had successfully imparted to an entire generation of whites the lesson that racial discrimination is unjust. It is thus churlish to suggest that working-class whites object to affirmative action only because it threatens their socioeconomic status. Presumably they object to racial discrimination for the same reason blacks and other groups do. Instead of making this point, however, Mr. Laham sets out to exonerate Pres. Reagan by distinguishing his motives from those of the venal white working class.

This book’s main arguments can be gleaned from the following representative passages:

There is no question that Pres. Reagan’s efforts to curtail federal enforcement of civil rights laws, especially affirmative action, yielded him enormous political dividends, allowing him to gain the support of millions of working-class whites who had previously voted Democratic in presidential as well as congressional elections.

Political considerations — specifically the need to attract working class whites — may have dictated that Pres. Reagan make reforms in affirmative action; however, other political considerations, especially the need to preserve the unity of the Republican Party, also dictated that he refrain from making any reforms in affirmative action.

Ultimately, Pres. Reagan’s civil rights policy was shaped more by the moderate Republican elites than by the conservative, often racist, perspective of working-class whites.

Laham’s conclusion that Pres. Reagan’s civil rights policy was shaped by moderate Republican elites is only partly correct. In fact, the administration’s approach to civil rights policy was chronically inconsistent. On the one hand, “moderates” like Labor Secretary Bill Brock and Secretary of State George Schultz opposed any effort to curtail racial preferences. On the other hand, the Justice Department under Attorney General Edwin Meese and Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights William Bradford Reynolds mounted an aggressive legal assault on so-called “reverse discrimination” — which meant, in effect, suing to dismantle hundreds of long-standing affirmative action programs.

Mr. Laham largely ignores the latter aspect of the Reagan civil rights record, concentrating instead on the role played by the moderates in obstructing attempts to eliminate some government-mandated racial preferences. The moderates succeeded, we learn, in scuttling efforts to revise an LBJ-era executive order that had led to the establishment of a system of minority set-asides in federal contracting. And they strongly objected to Pres. Reagan’s decision to veto the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1988.

These matters, though important, were not nearly as important a part of the Reagan record on civil rights as were the briefs the administration filed in several landmark federal court cases. One need only peruse contemporaneous press accounts, along with the hysterics of columnists such as Anthony Lewis and Tom Wicker, to appreciate the significance of this civil rights litigation. To the extent that the administration deviated from its predecessors on racial preferences, Mr. Meese and Mr. Reynolds led the way. Often facing stiff resistance from career staff attorneys within their ranks, they tried to restore the civil rights of white and male plaintiffs who had been victims of unlawful discrimination. Liberals were incensed.

In cases such as Williams v. New Orleans (1984), Firefighters v. Stotts (1984), Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education (1986) and Local 93, International Assoc. of Firefighters v. City of Cleveland (1986), the Justice Department under Pres. Reagan did something unprecedented: it invoked federal civil rights statutes to protect all Americans, including whites and men. Since in all of these cases the alleged discrimination was carried out in the name of “affirmative action,” the Reagan administration was rightly seen as attacking it.

Attention to these cases and the issues they raised might have prevented such conceptual blunders as Mr. Laham’s repeated references to “Reagan’s efforts to curtail federal enforcement of civil rights laws, especially affirmative action . . .” As it is, the odd notion that enforcing civil rights laws means defending racial preferences informs the entire book. To be sure, that is the orthodox view among contemporary liberals and “civil rights advocates.” But it is perversely out of place coming from an author whose stated purpose is to debunk “the stereotypical view of Reagan as a cynical and manipulative, though outwardly pleasant and likable, president, who shamelessly played the race card for his own political gain . . .” Rather, according to Mr. Laham, all the documented evidence currently available suggests that Reagan’s civil rights policy was motivated by his sincere and genuine desire to achieve colorblind justice and limited government, which served as the two core principles of his conservative agenda.”

True enough. But to imply, as Mr. Laham does, that the elevation of those objectives led necessarily to a devaluation of civil rights law betrays a lack of familiarity with the laws in question. Far from “curtailing” civil rights enforcement, it would be more accurate to say that the Reagan Justice Department tried to rehabilitate civil rights policy by introducing race- and sex-neutrality to the enforcement process. As for affirmative action “laws,” they did not exist. Instead, what we had in the 1980s — and still have to a considerable extent today — is a patchwork of pro-affirmative action judicial rulings and bureaucratically-administered programs that violate both the letter and spirit of the civil rights statutes. Mr. Laham’s failure even to mention any of the Reagan-era reverse-discrimination cases, much less to examine the jurisprudence behind them, blinds him to the fact that affirmative action as practiced in the United States for at least the last 25 years is unlawful.

Mr. Laham is partly correct in attributing Pres. Reagan’s ultimate failure to reform civil rights policy to divisions within his cabinet and, more generally, within the Republican Party. But he is naïve to characterize the opposing factions as “moderates” on the one hand, and “conservative working-class whites” on the other. His assertion that the latter were “often racist” is a gratuitous slur. Had he acknowledged the untenable legal status of affirmative action, Mr. Laham might have understood that by opposing it, Pres. Reagan was simply doing his constitutional duty to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” If Mr. Laham wished to explore motives, it would have been more appropriate to speculate about the intentions of those who wanted to preserve a policy that was at war with the law. Reading Mr. Laham, one would think that affirmative action supporters were beyond reproach; it is only Pres. Reagan who has something to answer for.

How sad that Mr. Laham’s defense of Pres. Reagan consists mainly in exonerating the former president of the racism and selfishness that he ascribes to working-class whites. Like them, Mr. Laham would have us believe Pres. Reagan regarded “civil rights” as an impediment to the realization of larger goals. But unlike them, his goals were the high-minded ones of limited government and colorblind justice. Thus Mr. Laham is able to conclude:

One can legitimately argue that Reagan’s commitment to colorblind justice and limited government often led him to compromise the cause of civil rights; but such compromises were motivated by his genuine political conservatism, not by any political desire he may have had to play the race card.

This is troubling for two reasons. First, one cannot in fact “legitimately argue” such a thing unless one believes that “civil rights” are nothing more than a grab bag of special privileges and group entitlements. Pres. Reagan, and most especially Mr. Meese and Mr. Reynolds, refused to accept that proposition.

Second, Mr. Laham uncritically accepts (and repeatedly uses) the hackneyed “race card” metaphor. To accuse someone of “playing the race card” has become a potent way to stop any attempt to discuss issues in which race may be a factor, no matter how remote or tangential. Thus, to talk honestly about crime, urban decay, welfare, immigration, or affirmative action is automatically to be accused of playing the race card. No wonder Mr. Laham cannot bring himself to realize that civil rights, properly understood, are antithetical to racial preferences. That would be playing the race card.