The Secrets of Getting into Harvard Were Once Closely Guarded. That’s About to Change.

Nicole Hong and Melissa Korn, Wall Street Journal, October 11, 2018

{snip}

A lawsuit accuses Harvard University of illegally discriminating against Asian-American applicants by holding them to a higher standard than students of other races. Harvard denies the accusation, saying race is just one of a complex matrix of factors it considers before handing out its coveted acceptances.

Harvard uses what it calls a holistic approach to admissions, considering not only an applicant’s academic record and test scores but also activities, formative experiences and personal attributes. {snip}

Elite colleges, 60% of which consider race in admissions, say the trial’s outcome could threaten their autonomy to craft undergraduate classes. If forced to exclude race from admissions considerations, many schools say, their student demographics would change significantly.

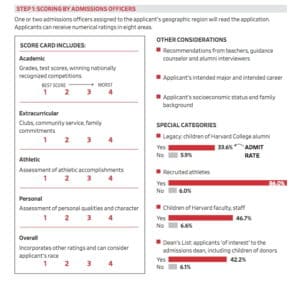

For years, Harvard has fought against the public release of documents showing the inner workings of its admissions office. Court filings in advance of the trial offer tantalizing details about how Harvard rates prospective students and how it considers race. The trial is expected to shed light on the magnitude of admission preferences for athletes, children of alumni and applicants with connections to major donors.

Among the more controversial aspects of the admissions process: Each applicant receives a “personal rating” reflecting, in part, an analysis of personality traits such as humor, courage and kindness.

The plaintiffs claim that Harvard’s own data show Asian-Americans received the highest academic and extracurricular ratings of any racial group, but the lowest personal ratings. In court filings, Harvard has attributed lower Asian-American personal scores to “unobservable factors” that come through in teacher recommendations, applicants’ essays and interviews, which are also factored into the rating.

{snip}

The lawsuit seeks to ban Harvard from considering race in future admissions decisions. It was brought by a nonprofit group, led by a conservative legal strategist, whose members include Asian-Americans rejected by Harvard.

Over the past 40 years, the Supreme Court has ruled repeatedly that universities can consider an applicant’s race to promote the educational benefits that flow from diverse campuses, including better preparing students for the workforce.

The presidents of Yale University, Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, among others, have filed a brief in support of Harvard, arguing that prohibiting colleges from weighing race in admissions would represent an “extraordinary infringement on universities’ academic freedom.”

The Justice Department has weighed in on the other side, filing a “statement of interest” supporting the plaintiffs. It launched its own civil-rights investigation last year into whether Harvard discriminates against Asian-American applicants. {snip}

A senior Justice Department official said the investigations are a priority for its Civil Rights Division. Harvard’s lawyers have called the government’s actions a “thinly veiled attack” on Supreme Court precedent and “so outside ordinary practices.”

{snip}

Harvard said in a court filing that eliminating affirmative action would give the biggest boost to white students, increasing their share in a recent admitted class to 48%, from 40%. The share of Asian-Americans would rise to 27%, from 24%, while African-Americans would drop to 6%, from 14%, and Hispanics to 9%, from 14%.

{snip}

Harvard Score Card

The Harvard trial is expected to last three weeks. U.S. District Judge Allison Burroughs will decide whether the school’s admissions practices, which have considered race since at least the 1970s, violate federal civil-rights law. Her decision is likely to be appealed, possibly to the Supreme Court.

{snip}

In lengthy court filings this summer, both sides previewed their trial evidence. Harvard sought to keep the material under seal, citing concerns about the privacy of applicants. The school said disclosing too much about its process would embolden paid college consultants to advise clients on how to conform to the perceived criteria, to the disadvantage of low-income applicants.

Harvard faces four claims at trial, the most significant of which accuses the school of intentionally discriminating against Asian-American applicants.

A key witness will be William Fitzsimmons, 74, who has been admissions dean since 1986. {snip}

The plaintiffs have accused Mr. Fitzsimmons and other Harvard officials of ignoring internal Harvard studies from 2013 that found being Asian-American decreases an applicant’s chance of admission and concluded Asian-Americans would account for 43% of the admitted class if based on academics alone. The plaintiffs allege in a court filing that Harvard “killed the investigation and buried the reports” instead of probing further.

Harvard said the reports weren’t shared widely because they were based on a preliminary analysis that didn’t take into account nonacademic factors. The reports weighed only 20 factors, Harvard said, compared with 200 factors considered in the school’s data analysis in connection with the lawsuit.

Another focus for the plaintiffs is the role of race in the “personal rating,” one of many scores applicants receive in the admissions process. The personal rating is the only category in which white applicants scored significantly better than Asian-Americans, the plaintiffs say, arguing that it reflects negative racial stereotypes. Harvard says admissions officers don’t consider race in the personal rating.

{snip}

The trial also is likely to delve into Harvard admissions preferences known as “tips.”

According to an economist’s report that analyzed Harvard admissions data on behalf of the plaintiffs, students with at least one parent who attended Harvard had an acceptance rate of 33.6%, compared with 5.9% for nonlegacy students. Nearly half of children of Harvard faculty and staff were admitted, and 86% of recruited athletes were, the report said.

The plaintiffs contended in pretrial filings the preferences overwhelmingly benefit white applicants. {snip}

{snip}

Former Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen, two Nobel laureates and more than a dozen other economists submitted a brief supporting the analysis of Harvard’s hired economist, who found being Asian-American had no negative effect on the likelihood of admission. A different group of economists from the University of Pennsylvania, Johns Hopkins University and other schools supported the plaintiffs’ analysis.

The plaintiffs also accuse Harvard of setting racial quotas, pointing to “one-pagers” that administrators receive throughout the admissions cycle, which compare statistics on the admitted classes from the current and prior year by race, gender and other categories.

Asian-Americans accounted for between 18% and 21% of admitted students for each class that graduated from 2014 through 2017, while Hispanic and African-American students each accounted for 10% to 12% over the same period.

Harvard said in a court filing it uses one-pagers to estimate what share of admitted students will enroll, and that the share of Asian-Americans in the admitted class has risen 29% since 2010.

The plaintiffs allege race plays such a decisive role in the admissions prospects of Hispanic and African-American applicants that removing all racial preferences would increase the number of Asian-American admissions by 40%. {snip}

The plaintiffs also say Harvard hasn’t followed the Supreme Court’s requirement to seriously consider race-neutral alternatives before resorting to affirmative action, arguing the school could achieve racial diversity by expanding financial aid, reducing legacy preferences and giving more weight to socioeconomic status.

Harvard says no combination of race-neutral methods would yield the same level of diversity and academic excellence. To admit the same number of African-Americans without considering race, Harvard says, the school would have to give more weight to socioeconomic status than to academic qualifications.

Eight current and former Harvard students, including Asian-Americans, are expected to testify at trial on behalf of Harvard about how racial diversity improved their college experiences.

{snip}

The plaintiffs don’t intend to call any Asian-American students as witnesses, sparking criticism from some advocacy groups that the lawsuit is using Asian-Americans to press for a policy shift that would benefit white students most.

These advocates argue eliminating affirmative action will exacerbate the effect of some preferences, such as legacy admissions, that primarily help white applicants. “You’re really going after the wrong culprit,” said Nicole Gon Ochi, a lawyer for Asian Americans Advancing Justice, which filed a brief supporting Harvard.

{snip}