Serena Williams and the Trope of the ‘Angry Black Woman’

Ritu Prasad, BBC News, September 11, 2018

Mammies, jezebels, Sapphires. Black women in America have long been dogged by negative stereotypes, rooted in a history of racism and slavery. In the aftermath of Serena Williams’ controversial US Open loss, it’s the trope of the “angry black woman” that has once again re-emerged.

During the US Open final, Williams received a code violation for coaching, a penalty point for breaking her racquet and a game penalty for calling the umpire a “thief”. And later, a fine of $17,000 (£13,000).

Her reactions to the referee’s calls — which the Women’s Tennis Association has since decried as “sexist” — were no different from how many top players react in the heat of a championship game.

But it was the way she was punished for her anger that has sparked further outrage.

“As it was unfolding I could tell this was not going to turn out well,” says law professor Trina Jones. “I knew it was going to be a trainwreck.”

In addition to being a long-time tennis fan, Prof Jones has studied racial stereotyping and how it plays into the lives of African-American women.

“Black women are not supposed to push back and when they do, they’re deemed to be domineering. Aggressive. Threatening. Loud.”

Similar words have been levelled at Serena Williams more than once, as well as former First Lady Michelle Obama and top Democrat Maxine Waters in recent years.

Williams has been docked before for her behaviour on the court — in 2009, she was fined $82,500 for an angry outburst — though she is far from the only player to face punishment for similar conduct.

Prof Jones says some have compared the referee’s calls to speeding tickets: many people speed and sometimes a few are caught.

But that analogy, she says, misses the point that African Americans are disproportionately pulled aside. In the case of Williams, she was first dinged on a coaching violation that happens often but is rarely called out as the player’s fault.

“Why would a black woman in a championship match therefore be called on it?” Prof Jones says, adding that an attack on one’s integrity is only natural to be angry about.

“[Williams] is outraged because she knows the context.”

The “angry black woman” trope has its roots in 19th Century America, when minstrel shows, which involved comic skits and variety acts, mocking African Americans became popular.

Blair Kelley, associate professor of history at North Carolina State University, says black women were often played by overweight white men who painted their faces black and donned fat suits “to make them look less than human, unfeminine, ugly”.

“Their main way of interacting with the men around them was to scream and fight and come off angry, irrationally so, in response to the circumstances around them,” she says.

The 1930s programme Amos ‘n Andy was one of the first modern media portrayals to cement this stereotype through the character of Mrs Sapphire Stevens.

“The real problem in their everyday life was not the structural things that black people faced, but the mouth of the black woman — her tone, her irrationality and her anger,” Prof Kelley says of Sapphire’s role.

As segregation laws known as Jim Crow laws saw black Americans assaulted, jailed and killed, popular culture pushed ideas of “sassy mammies” and “Sapphires” — an archetype depicting black women with iron-fists, yelling at everyone from children to white men.

This trope of the “angry black woman” has endured, and has been pervasive in modern media even without more overtly racist portrayals, says Brandi Collins, senior campaign director at the racial justice organisation Color of Change.

On screen, it is easy to push sass for laughs. But black women in America see these depictions translate differently in real life.

For Ms Collins, the picture of the “hyperemotional” black woman has become more commonplace as Americans grapple with issues of polarised politics and civility.

Black women, she says, are often faced with people responding to their emotions “from a place of perceived fear”.

“There’s almost a paranoia around it. A feeling that you have to go above and beyond to make people feel comfortable around you.”

In a 2016 interview with Oprah Winfrey, former First Lady Michelle Obama echoed the same sentiment.

“You think, that is so not me! But then you sort of think, well, this isn’t about me,” she said of being labelled as an “angry black woman”.

“This is about the person or the people who write it… We are so afraid of each other, you know?”

Robin Boylorn, an intercultural communications professor at the University of Alabama told the BBC it seems impossible to be a black woman and not be angry, after “generations of oppression, discrimination and erasure”.

“Black women should be celebrated for not being completely consumed by anger,” she says.

“Men are allowed to be angry as a performance of masculinity. White women are allowed to be angry as a clarion call. So black women should be encouraged to express their anger as well, particularly in the face of injustice.”

For Serena Williams, Prof Boylorn says the issue is compounded by the fact that “she cannot separate her blackness from her womanhood, from her class or social status”.

But it’s the double standard with men in particular that has come up in the ongoing debate of Williams’ US Open performance.

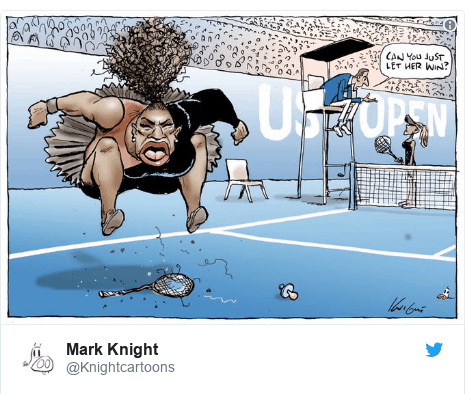

In a cartoon that went viral after the final, Williams is drawn as a petulant, mannish figure while the referee tells her opponent, “Can you just let her win?”

“It’s indicative of the way in which Serena has been, throughout her career, treated both by media and within US tennis as angry, unhinged, really aggressive,” says Ms Collins of Color of Change.

“When you see her be degraded or treated in that way, it really can lead young black girls and girls in general to question whether or not they should be the full range of what it means to be a woman.”

But Ms Collins notes that fixing the problem is not just about eliminating the “angry black woman” trope.

“For every type of white man you can imagine, there’s a movie about his story and his experience and his journey. Black women in media aren’t afforded that diversity of experience,” she says.

Instead, understanding the diversity of a black woman’s experience — and not just her anger — is key.

For Williams, that’s a lesson she hopes her fans will learn from her US Open upset.

“I’m here to fight for women’s rights and women’s equality. The fact that I have to go through this is an example,” she told reporters after the match.

“Maybe it didn’t work out for me, but it’s going to work out for the next person.”

Ritu Prasad