Genetic Intelligence Tests Are Next to Worthless

Karim Kadim, AP, May 29, 2018

I often consult a website called DNA.Land, run by a team of scientists affiliated with the New York Genome Center who use it to collect genetic data from volunteers for scientific research. {snip}

On a recent visit to DNA.Land, I scanned down the list of traits they offered to tell me about. I stopped at intelligence.

I took a breath before I clicked.

Intelligence, after all, is different from the smoothness of your teeth or your risk of skin cancer. {snip}

{snip}

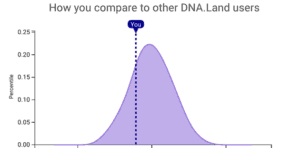

I took a breath and clicked on the link. I was swiftly sent to a new page, entitled “General Intelligence Trait Prediction Report for Carl Zimmer.” And on that page, here’s what I saw:

The bell curve was surrounded by notes, disclaimers, and symbols. But my eye stayed locked on that lavender hill — especially on that personalized marker that located me on the low side of the scale.

What was I to make of this? For some reason, DNA.Land’s prediction felt more profound than if I had taken an actual IQ test. It didn’t depend on whether I could recall some random string of words at a particular moment. Instead, I was looking inside myself, at the immutable genes that shaped me from before birth.

{snip}

I called up Yaniv Erlich, the scientist who wrote the intelligence program, to ask him about his prediction. Erlich, I should point out, majored in computational neuroscience, got a Ph.D. in genetics, became an associate professor at Columbia, and is on leave from teaching to serve as the chief science officer at the DNA-testing company MyHeritage. {snip}

I bring all this up because Erlich burst out laughing when I told him about my report and told me about his own.

“I also get that on the left side,” he said. “Everything is cool. Many smart people end up there.”

Erlich explained that he designed the program to make people cautious about the connection between genes and intelligence. All those disclaimers and notes that surrounded the bell curve were intended to show that these predictions are, in a sense, worse than just wrong. They’re practically meaningless.

The inspiration for the program was a 2017 study pinpointing certain genes with some sort of connection to intelligence. For decades, scientists knew that the genes we inherit play a role in the variation in scores on intelligence tests. Studies on twins and families show that people who share more genes in common tend to get closer scores. The 2017 study, carried out by a team of researchers based at Vrije University Amsterdam, was one of the first to find a statistically strong connection between that variation in scores and specific genes.

{snip} In a study of over 78,000 people, the Amsterdam team found variants in 52 genes that are unusually common in people who score higher (or lower) on intelligence tests.

{snip}

If you discovered that you had one of the variants identified by the Amsterdam team, that would not jack up your IQ by 50 points. Each one is only associated, on average, with a shift of a fraction of one point.

Erlich’s program checks those 52 genes in the DNA of his volunteers. It determines the effect that each variant has on each person, adding up all the slightly positive and negative effects to determine their total impact.

In most cases, they all pretty much cancel each other out. That’s why Erlich ended up with a bell curve, with its peak around a net effect of zero. In my case, the score-lowering variants slightly outweighed the score-raising ones, leaving me — like Erlich — on the left side of the curve. And I do mean slightly. Each of those ticks on the horizontal axis of the bell curve represents five IQ points. Erlich predicted that the effect of my 52 genes added up to less than a point.

But there’s an even deeper illusion to my bell curve: The seeming precision is almost certainly wrong.

When geneticists use the word prediction, they give it a different meaning than the rest of us do. {snip}

{snip} When they try to predict a trait from a set of genes, their prediction may be dead on, or it may be no better than random. Or, as is almost always the case, it is somewhere in between.

Genes that predict the variation in a trait perfectly in a group of people have a predictive power of 100 percent. If they’re no better than what you’d get from blind guesses, their power is zero. The Amsterdam team tested their 52 genes on thousands of people and concluded that the genes have a predictive power of nearly 5 percent. Their predictions are less than random, {snip}.

This weak power is no surprise to scientists who study the heredity of height, blood pressure, and other complex traits. Their variations arise from many genes — sometimes thousands of them — as well as variations in the environment.

That doesn’t mean that scientists won’t get better at predicting intelligence. {snip}

Scientists are now studying even bigger groups of over a million people, and it’s likely their powers of prediction will jump yet again. But in years to come, they won’t keep leaping to 100 percent. When researchers study identical twins, they find that their intelligence test scores tend to be closer than fraternal twins. But they’re not identical. That’s a sign that genes are not the only force that shapes our intelligence. In fact, only roughly half of the variation in intelligence test scores arises from variations in genes.

{snip}

Even if scientists only manage to reach a predictive power of 25 percent, we could learn a lot from their work. Researchers are already finding that genes linked to intelligence tend to do certain things and not others. A lot of them switch on when neurons divide into new neurons, for example. Social scientists could take DNA into account in experiments to determine the best ways to help children learn and stay in school.

But with millions of people flocking to sites like 23andMe and Ancestry.com to get reports on their genes, we have to wonder what will happen if they start handing out intelligence predictions.

After talking with Erlich, I fear it will turn out badly.

{snip}