Why Men Fight

Jon Harrison Sims, American Renaissance, July 2007

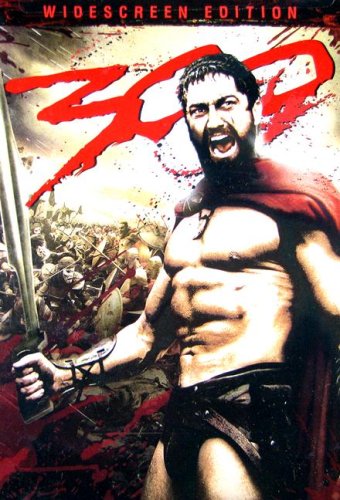

300, directed by Zack Snyder, starring Gerard Butler and Lena Headey, Warner Brothers, 2007.

In 480 BC, King Xerxes of Persia, absolute ruler of the greatest empire in the world, led an army of hundreds of thousands of infantry, tens of thousands of cavalry, and over 1,000 warships, against the independent city-states of southern Greece.

In the East, his empire stretched from the Arabian Sea to the Aral Sea, and from eastern India to the Persian heartland. In the west, it looked like an enormous claw clutching the eastern Mediterranean: Egypt and Libya to the South and Thrace to the North were Persian satrapies. The Greeks of the eastern and northern Aegean had already fallen to Persia. After Xerxes’ army crossed into Europe, the other Greeks began to waver. Thessaly sent tokens of submission; Thebes and Argos followed. Only Sparta and Athens, and their allied cities, remained defiant.

The narrow pass of Thermopylae, bordered by mountains and the sea, guarded the entrance into southern Greece. It was known as “the Gates,” and it was here that the Greek high command chose to make a stand. King Leonidas of Sparta marched to the pass with 300 of his best warriors, along with 2,800 Peloponnesian and 1,100 Boeotian allies.

Xerxes could not believe that this small force dared oppose him. He actually waited four days, expecting them to flee. When they did not, he became enraged, and ordered his Median troops to arrest them and make them answer for their insolence. The Greeks, fighting in close-order phalanx, slaughtered the Medes. The next day, he sent in his elite Persian infantry, “the Immortals.” The Greeks, fighting in shifts to keep up their strength, killed thousands. On the third day, it was the same. An army of 300,000 had been stopped in its tracks by less than 5,000 men.

That night a traitor, Ephialtes the Malian, showed the Persians a goat path through the mountains to the rear of the Greek position, and by morning, the Hellenes were surrounded. Leonidas dismissed his allies, but he and his men, along with 700 Thespians from Boeotia who refused to abandon their Spartan allies, chose to stay and fight to the death. Leonidas held his ground in obedience to Spartan law, which forbade retreat, but also out of piety toward the Pythian oracle at Delphi, who had foretold that either Lacedaemon (the area around Sparta) would be sacked, or a Spartan king would fall. He thought it far better to die in battle than let the Persians ravage his homeland.

There have been only two films made of this battle: Rudolph Mate’s The 300 Spartans in 1961, and now Zack Snyder’s 300. Mr. Snyder’s is not only better, it could be the best film ever made about ancient Greece.

Some might doubt this judgment. Mate filmed on location in Greece, and he added very little to the historical facts as we know them. Mr. Snyder filmed everything in a warehouse in Montreal, designing his landscapes on a computer, and he altered and embellished history in unnecessary ways. He portrays the ephors, an elected Spartan magistracy, as a lecherous and leprous cabal. The Spartan Senate is under the influence of a conniving politician, which would have been inconceivable in Sparta. Mr. Snyder also adds battle elephants, a rhinoceros and a raging giant to Xerxes’ army.

Yet experts say the dialogue is authentic and powerful. Barry Strauss, a classical scholar, whose recent book Salamis is about the Athenian naval victory that followed soon after Thermopylae, says the Spartans in the film speak like Spartans. Many film critics have ridiculed the language, but this tells us more about them than about the excellent screenplay, which is adapted from Frank Miller’s novel, 300.

The film is one of the most beautiful ever made. Every frame is like a painting. The fierce Spartan warriors stand in sartorial splendor. They wear dark red cloaks across their shoulders, bronze Corinthian helmets, bronze-tipped black spears, and bronze shields emblazoned with the Greek L (L) for Lacedaemon, their homeland. Mr. Snyder’s computer-generated mystic landscapes are bathed in brown and gold. The effect is otherworldly, and what is lost in realism is gained by conveying a sense of antiquity; this truly seems to be the ancient world.

The battle scenes are spectacular, and not at all repulsive or gory. The director used computer graphics to portray the brutal reality of ancient combat — essentially hand-to-hand dismemberment — without sickening the audience with carnage. We also see why the Spartans were considered invincible. Their training, athleticism, and tactical prowess, combined with Greek armor, made them the best warriors in the world for centuries.

There are many memorable scenes. In one, as the Spartans march off in their red cloaks, Leonidas lingers to say goodbye to his wife, Queen Gorgo (Lena Headey). She does not weep like a Hollywood heroine; instead, she tells her husband to return either with his shield or on it — that is, either victorious or dead. She bolsters his courage rather than distract him with tears.

Ignorance of History

The establishment media have treated the film with contempt and derision that are neither surprising nor hard to explain. The reviewers are ignorant of history and hostile to Western culture, especially when it is portrayed heroically.

The New York Times’ A.O. Scott described the film as “violent as [Mel Gibson’s] Apocalypto and twice as stupid.” He complained that Xerxes is caricatured as a “self-proclaimed deity who wants, as all good movie villains do, to rule the world.” Mr. Scott is so ill-educated that he does not know that is exactly what Xerxes wanted. According to Herodotus, he had his eye on Italy and hoped eventually to conquer the whole Mediterranean. His Carthaginian allies had launched a simultaneous operation against the Greek cities in eastern Sicily.

The Washington Post’s Stephen Hunter called the film an “overblown visual document with an IQ in the lower 20s.” He complained that Mr. Snyder “doesn’t even bother to mention the strategic context” of the battle or “to follow the story to its end at Salamis.” That’s because the movie is about the Spartans, not the Athenians; and Mr. Synder does follow the story to its end, at Plataea, where a combined Hellenic force, led by the Spartans, crushed the Persian army and ended the war. Mr. Hunter appears to know nothing about Hoplite warfare either. He complained that one scene, when the Spartans break the initial Median charge, shows “war as Ohio State football.” This is actually one of the most realistic battle scenes in the film.

Some reviewers have denounced the film as racially incorrect. The St. Louis Post Dispatch’s Joe Williams sneered that “it is surely no accident that the ‘Asian hordes’ are depicted as dark-skinned degenerates.” Mr. Scott of the New York Times complained that “unlike their mostly black and brown foes, the Spartans . . . are white.” The most bizarre reaction came from two Iranian-American leaders, interviewed on National Public Radio, who called the movie “all lies” and insisted that it was the Persians who were blonde and blue-eyed and the Greeks who were dusky.

Xerxes did have some white troops — Thracians and eastern Greeks — but he did not trust them and none took part in the battle. Most of his troops were brown-skinned Asians, although there were some blacks from Ethiopia. Friezes from the Persian palace at Persepolis clearly show Xerxes with Near Eastern features, while ancient Greek statues leave no doubt that the Greek aristocracy was largely Nordic. Casting a tall Scotsman (Gerard Butler) as Leonidas is exactly right.

Some see the film as military propaganda. David Denby of the New Yorker called it a “porno-military curiosity, a muscle-magazine fantasy crossed with a video game and an Army recruiting film.” Alas, some Americans may see it that way, but the insightful will see in the multicultural Persian empire the prototype of their own, and in the Greeks a symbol of the unity and vigor we have left behind.

1836

In 1836, at a former Spanish mission converted into a makeshift fort, 188 Americans held off a Mexican army of 3,000 for ten days before being slaughtered. There is no doubt that their commander Col. William B. Travis, South Carolina born and classically educated, knew of the example set over 2,300 years earlier by King Leonidas. Like the Greeks, Americans were determined to fight the invader.

Only a hundred years later, Americans had changed. They built a memorial to those who fought in the First World War and wrote on it of a messianic ambition: “they strove that war might cease; for liberty and world peace, they were willing to die.”

The Greeks were never so foolish as to believe that war might cease, or that it was worth dying for such chimeras as world peace or democracy. Nor were they so foolish as to extend citizenship to non-Greeks, to resettle Persian prisoners in their cities (as the Americans did Iraqis after the first Gulf War), or to extol diversity.

If the Greeks had been as multicultural as 21st century America, they would have succumbed to the Persians without a fight, for they would have seen no reason to resist such a benevolent and diverse imperium. The Athenian dramatist Aeschylus, who himself fought in the Persian wars, writes that his countrymen sailed into the epic sea battle off Salamis with the cry: “O Greek sons, advance! Free your father’s land! Now the contest’s drawn: All is at stake!” Those are the sentiments with which real nations march into battle.