In Praise of Arthur Jensen

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, September 2004

Helmuth Nyborg, Editor, The Scientific Study of General Intelligence: Tribute to Arthur R. Jensen, Pergamon, 2003, 642 pp.

Arthur Jensen, professor emeritus of educational psychology at U.C. Berkeley, is one of the great scientists of our time. No one has played a larger role in rescuing the study of intelligence from radical environmentalism. No one has so patiently and carefully studied the most unpopular and maligned subjects in psychology: the biological bases of intelligence and the question of racial differences. And no one else has advanced the field as he has, nor suffered as much for doing so. If Prof. Jensen had made equal contributions to any less controversial field, he would long ago have been honored as one America’s most prominent thinkers.

Arthur Jensen

However, even if the wider society continues to ignore or revile him, Prof. Jensen’s professional colleagues have begun to recognize his remarkable contributions. A special issue of the journal Intelligence, dated November 3, 1998, collected a number of articles under the title “A King Among Men: Arthur Jensen.” Fellow scientists like Philippe Rushton, Linda Gottfredson, Sandra Scarr, and Thomas J. Bouchard wrote sometimes moving tributes to a man who is sure to take his place with men like Francis Galton and Charles Spearmen as a giant in his field.

Some of the same authors have returned for a new volume in honor of Prof. Jensen edited by Helmuth Nyborg of the University of Aarhus in Denmark. This is a massive work of more than 600 pages, which amounts to both a tribute to a great man and a summary of our current knowledge about intelligence.

Many of the 31 contributors start by noting the qualities that make Prof. Jensen such an outstanding scientist. They admire his ability to spot the slightest flaw in research methods, and his overwhelming commitment to data. Preconceptions, preferences, even his own positions mean nothing to him if the data do not support them. As Sandra Scarr has said, “For him, impressions and feelings are not data and have no place in psychology.”

Prof. Nyborg writes that Prof. Jensen will eagerly analyze good data with a completely open mind even if it contradicts his own theories. Integrity of this kind is rare in any field, and has undoubtedly been crucial to his ability to maintain the respect of his profession while he undermined the fundamental convictions of most of its members.

The common scientific point of departure for the authors in this book is g, or the general factor for intelligence. Prof. Jensen’s work on g is probably the most significant of the many areas in which he has made important contributions.

It is now widely recognized in the field of mental testing that there is a human mental capacity known as g that is the basis for essentially everything we describe as intelligence. There are many specialized mental skills but g can be thought of as the common power source that drives them. g can not now be measured directly, but it can be calculated statistically from results of a battery of tests. All valid intelligence tests therefore test some aspect of g, and some come closer to measuring it directly than others. The extent to which a test’s results are close to those calculated from an entire battery of tests is called a test’s g loading.

People have different combinations of mental abilities, but because all of them are powered by g, people who are good at solving one kind of mental problem are usually good at others. With some exceptions and much variation, people who are good at working out word analogies are likely to be good at math, reading comprehension, geometry, spatial relations, and even such things as business or car mechanics. We are only just beginning to understand the brain functions that constitute g and to find the genes needed for them. Prof. Jensen himself describes molecular genetics and brain physiology as the new frontier for intelligence research.

A vast, wide-ranging volume

It would not be practical to critique or even mention all the articles in this vast and wide-ranging volume. They are organized by subject, such as “The Biology of g” or “The Demography of g,” and this review will only touch on a few highlights.

The search for the underlying biology of g has begun, but persistent public ignorance about the nature of intelligence means there is practically no funding for it. Richard Haier of U.C. Irvine points out that research on schizophrenia finally established that the disorder has a strong genetic component. Government and drug company funding promptly shifted to a search for the underlying physiology of schizophrenia in the hope of finding a cure. People who had theorized that “the cold mother” could cause the disease were out of a job.

Prof. Haier notes there has been no such shift in intelligence research. There are still plenty of well-funded proponents of “institutional racism” as the cause of low black IQ, despite the fact that a biological understanding of g has vastly more potential applications than an understanding of schizophrenia. It may some day be possible to cure mental retardation and stop the decline of intelligence in old age, but society will first have to get over the idea that the main influence on IQ is household income.

At this point our knowledge is very crude. We know, for example, that brain size has something to do with intelligence, but a size/IQ correlation of only 0.35 means there are other physiological functions that also explain differences in intelligence. Matching blacks and whites for intelligence produces matching brain sizes, but matching blacks and whites for brain size alone does not produce a match in IQ — the whites are still somewhat smarter. A certain level of brain size is necessary for high intelligence but it is not sufficient.

Since the appearance of this book, Prof. Haier has reported elsewhere that variations in the amount of gray matter — as opposed to white matter — in particular locations of the brain appear to be related to intelligence, but that these locations vary as a person matures. For young adults, a greater accumulation of gray matter in the temporal areas is associated with high intelligence; for middle-aged people, the frontal and parietal regions are more important. Dr. Haier is now looking into sex differences in these patterns.

In any case, size is clearly not all that matters. By age six, a child already has a brain that is 92 percent of its final adult size. The increase in mental ability after age six is therefore not greatly dependent on adding brain mass, but no one understands the changes that are taking place in the brain that make a person smarter as he matures.

Efficiency in the brain’s use of its primary fuel, glucose, appears to be one factor. Smart people’s brains use less glucose than dim people’s brains. Also, people use more glucose when they first try something mentally challenging than after they have had a lot of practice — and the reduction in glucose requirements after practice is greater for smart people. People with mental retardation or Down’s Syndrome seem to consume about 30 percent more glucose than normal people.

What is called “inspection time” is also a direct indicator of intelligence. People cannot make out an image flashed on a screen for just a millisecond or two, but as flashes get longer they begin to see the image. Scientists learned as early as 1976 that bright people see the images sooner than dim people — they need less “inspection time.” The correlation with intelligence is -0.5, and seems to reflect basic efficiency of neural processing that is related to intelligence.

The genes for intelligence have been very hard to find. The causes of single gene disorders are usually easy to find; if someone has (or doesn’t have) a particular expression of a gene, he has the disease. Intelligence seems to depend on accumulations and combination of many genes, each of which contributes only a little. This makes it hard to find stark genetic differences between smart and not-so-smart people.

Some day, the genes will be found and the biology of intelligence will be understood, and that day will bring far more benefits than “social programs” ever did. As Prof. Haier explains:

“[A] prevalent assumption underlying the (artificial) nature versus nurture debate was that something caused mostly by environment could be changed relatively easily, whereas something caused mostly by genes was essentially immutable. As we enter the 21st Century, just the opposite may be true. We are becoming quite expert at changing biology and genes; we still don’t improve environments with much precision of positive outcome. To the extent that low intelligence is genetic/biological, the prospects are increasing that neuroscience-based manipulations over the next decades may promise improvement where environmental-based manipulations have so far proved mostly unsuccessful.”

Although students of intelligence tend to be interested in high IQs, there is much to be learned at the low end, too. For example, there is a normal distribution of intelligence that takes the shape of the standard bell curve. However, at the very lowest levels are people who suffer from genetic diseases or who have had physical brain damage. Their plight is not the result of normal distribution, and this group forms a small hillock at the left-most end of the declining curve. Whites with IQs in the 60 and 70 range tend to suffer from conditions of this kind because the standard distribution of intelligence among whites does not often result in IQs this low. They tend to be obviously abnormal in appearance and behavior. Blacks, on the other hand, are much more likely to have IQs in this range simply because of standard distribution, and therefore do not appear or act obviously defective.

Another interesting finding is that people with low IQs tend to perform consistently on intelligence tests, whereas intelligent people get scores that vary — up and down — over time. This is probably related to the fact that people with high levels of g also tend to have greater variety in specialized mental skills. Low g people do not have this variety — except for the notable exception of savants, who may have striking musical or mathematical abilities despite low general intelligence.

The Demographics of g

Liberals seem better able to accept genetic causes for individual rather than group differences in g. If g were distributed equally across different groups — in particular, if blacks were as smart as whites — genetic explanations would triumph easily. Because of the intense hostility to racial differences, there is reluctance even to admit they exist, much less discuss their origins.

That there are differences, however, cannot be doubted. As Richard Lynn of the University of Ulster explains, different nations have different average levels of IQ that reflect their ethnic makeup. The lowest average IQs are found among the Australian Aborigines, with scores of about 71, and among sub-Saharan Africans, with scores of about 69. The highest average IQs — in the 103 to 106 range — are in northern Europe and especially Asia. Probably because of the effects of Communism, average IQs in Russia and East Europe appear to be in the mid-90s, though the data are bad because the Communists banned intelligence research. In some of the most primitive countries, notably in Africa, IQ studies of school children may be unreliable because many children do not know their ages. Because IQ rises during childhood, correct results require accurate age data.

Prof. Lynn notes that the association between race and IQ is so strong, it is possible to make accurate predictions of average national IQ on the basis of ethnic mix alone. He points out there is no environmental explanation that accounts for such consistent results.

Philippe Rushton of the University of Western Ontario goes further into the evidence for the biological basis of race differences. Prof. Jensen, he points out, was among the first to write about the significance of life history differences between races — that blacks mature more rapidly than whites, and that they have higher rates of non-identical twinning. It was these and other observations about racial differences that gave rise to Prof. Rushton’s own ground-breaking work on r-K theory.

Prof. Rushton also emphasizes the importance of the link between inbreeding depression and black/white differences in test scores. The children of marriages between close relatives tend to have lower-than-normal intelligence; this is a recognized genetic phenomenon known as inbreeding depression. Performance is not, however, depressed equally on all intelligence tests, and as it happens it declines most on those tests for which the black/white gap is greatest. This is hardly to be expected if the black/white gap is caused by environmental effects, but entirely consistent with the view that there is a substantial genetic contribution to racial differences in intelligence. As Prof. Rushton observes, inbreeding depression data from as far away as Japan can be used to predict the tests on which whites outperform blacks by the largest margin — a connection disbelievers in genetics are unable to explain.

Regression towards the mean provides further evidence. The general tendency in sexual reproduction is for parents with extreme characteristics to have children who are beyond the average in those characteristics but not as extreme as the parents. Very tall people are likely to have children who are tall but not as tall as themselves. There is a tendency to regress to the mean or average height.

The same is true with intelligence, except that black children regress to a mean of 85 while whites regress to a mean of 100. This explains why children of successful, high-income blacks do not do nearly as well as their parents. The SAT scores of black children who come from households with incomes of $70,000 or more are lower than the scores of white (and Asian) children from households with incomes of $20,000 or less. The black parents may have high IQs but their children tend to be pulled down by the low racial mean to which they regress.

Matching black and white children with unusually high IQs produces evidence for the same phenomenon. In general, if researchers find a child with a very high IQ, his brothers and sisters will turn out to have lower IQs. Genetic combinations that produce very high IQs are uncommon, and the IQs of other members of the family tend to decline toward the mean. The siblings of very high-IQ blacks, however, have lower average IQs that those of very smart whites. When blacks and whites are matched at IQs of 120, the black siblings have an average score of 100 whereas the white siblings have an average of 110. In both cases, the siblings are above average for their race, but the blacks are pulled back towards a lower average. There is the same tendency at quite low IQ levels. When white and black children are matched for IQs of 75, the whites’ siblings have higher IQs than the blacks’ siblings.

Another argument for a genetic component to the black/white difference is the effect of miscegenation. For people of mixed race, more white genes correlate with larger brains and higher IQs.

In one of the most interesting chapters in the book, Helmuth Nyborg respectfully dissents from one of Prof. Jensen’s important findings in The g Factor: that men and women have the same IQ distributions. Prof. Jensen conceded that the question of sex differences in IQ is “technically the most difficult to answer . . . the least investigated, the least written about, and indeed, even the least often asked,” but concluded there are no sex differences in either average or standard deviation.

Prof. Nyborg points out some of the difficulties in studying the question. First, IQ tests, in particular the popular Wechsler test, are designed deliberately to give sex-neutral results. It is well known that men do better at mathematical/spatial problems and women at verbal problems, so the mix is carefully balanced to give equal results. Also, because girls develop more rapidly in intelligence than boys, data from child testing gives artificially high results for girls and are not valid for the population at large. Prof. Nyborg concludes that there is a male advantage in average IQ of perhaps four to six points, but that it does not appear until puberty. He speculates that the brain may change in important ways at that time, just as the body changes.

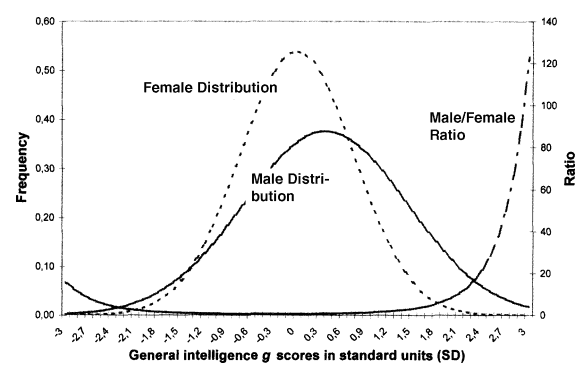

Prof. Nyborg also finds that the standard distributions of intelligence differ by sex, with women clustered nearer the average and men spread out towards both high and low IQs (see graph below). This means there are proportionately more male retardates. However, since the male average is four to six points greater than for women — the entire curve for men is pushed to the right — the real disparity in numbers is among the very intelligent, with men outnumbering women 120 to one at IQs of three standard distributions above the average (IQs of 145).

Proportions of this kind would explain male dominance in almost all fields, especially in mathematics, chess and physics. Likewise, female verbal ability would explain the large number of female writers. Prof. Nyborg is well aware of the resistance to his findings but argues that “the study of sex differences in general ability has long been hampered by ideology run amok.”

Prof. Nyborg also finds that high levels of testosterone boost IQ in women but depress it in men. He suggests that as far as intelligence is concerned, it would be useful to have at least four sex categories, not just two. He concludes that mannish, high-testosterone women and effeminate, low-testosterone men tend have the highest IQs, whereas macho men and effeminate women tend to be less intelligent.

Life as an IQ test

Linda Gottfredson of the University of Delaware is well known for her work on the relationship between IQ and how we live our lives. As she points out, a low IQ is associated with many things we want to avoid: crime, welfare, illegitimacy, and poverty. She writes that even the likelihood of dying in an automobile accident steadily increases three-fold as IQ declines from 115 to 80. Likewise, a certain level of intelligence is required to understand how disease affects the body or to figure out what dose of medicine to take. As Prof. Gottfredson explains, small mistakes add up: “g exerts its major effects on life outcomes largely by consistently tilting the odds of success and failure in the smaller events that eventuate in the more consequential outcomes.”

g is also the best single predictor by far of job performance. The more complicated and demanding the job, the more important it is to be smart; specialized knowledge or experience can be a leg up at first, but long-term success takes brains. The most respected, best-paid jobs are the ones that require the most intelligence, but high g is valuable even for menial jobs. A smart dishwasher works more consistently and responsibly than a stupid one. Conscientiousness is another measurable trait that predicts job performance but not nearly as well as general intelligence.

Specialized job tests — if they have any validity at all — show different pass rates for different groups. Prof. Rushton cites a Dutch “safety aptitude” test used to hire such people as locomotive engineers and bus drivers. Different ethnic groups scored in the same rank order on this test of motor coordination and concentration as they would have on an IQ test. Many people put great faith in specialized evaluations, but experts know that general intelligence is easier to test and usually gives more reliable results.

Lee Ellis of Minot State University in Minot, North Dakota, and Anthony Walsh of Boise State University in Idaho have contributed a very interesting chapter on the connection between IQ and crime. They refine the well-known association of criminality and low IQ by pointing out that criminals have a marked disadvantage in verbal rather than spatial/mathematical IQ, in which they may even be above average. Verbal IQ is what it usually takes to succeed in life by ordinary means — outside of specialized, math-oriented professions — so it is not surprising that the smash-and-grab mentality arises in its absence.

The two authors also refute the view that jails are filled with dummies only because the smart criminals don’t get caught. First, low IQ scores are very often found in aggressive, problem children, and they are the ones most likely to become criminals. Criminals are usually the least intelligent members of their families. Also, when researchers ask people to describe their own law-breaking, the ones with the most to tell fit the jail bird mental profile. Finally, if a researcher gives IQ tests to criminals about to be released, the scores are not a good predictor of recidivism. The smarter ones are just as likely to end up back in jail as the dim ones.

One theory about crime is that it is a battle between brain hemispheres. If someone’s left hemisphere, which handles language and moral reasoning, is unable to control the impulses of his more gratification-oriented right hemisphere he commits crime. An inability to control the right hemisphere seems to be linked to testosterone, which would help explain why men are more likely than women to be criminals. Blacks have higher testosterone levels than whites, and are vastly overrepresented among criminals.

It is now well established that money does not raise IQ. Children reared with all the social advantages show some gains in IQ compared to children without them, but these differences fade by early adulthood, when people choose their own environments, and the genetics of intelligence predominates. This is a well-established truth that liberals refuse to accept. They are happy to agree that people who don’t have “basic skills” will not get ahead, but they deny that illiteracy, for example, is a reflection of low g. For them, it must be caused by “oppression” or “racism.”

The volume ends with testimonials from Prof. Jensen’s former students, who praise his patience and his ability to explain complicated ideas. Helmuth Nyborg also offers a concluding chapter on what he calls the “collective fraud” of an academic establishment that will not face the evidence on intelligence. This is not merely an academic matter for, as he points out, “Policies for a make-believe world are doomed to failure.” Our social programs are like trying to go to the moon without understanding gravity or inertia.

Prof. Nyborg writes that Prof. Jensen’s brushes with mob violence remind him of Voltaire’s observation that “it is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong.” Prof. Nyborg is confident that good sense will eventually prevail but quotes Max Planck: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” Unfortunately, the generation now in school seems no better informed about intelligence than the generation of the 1960s.

This is an excellent and timely tribute to Arthur Jensen. Unfortunately, its staggering price — $125.00 — means practically no one buys it. Pergamon Press, like Praeger, which has published Richard Lynn, Michael Levin, and Prof. Jensen himself, seems to specialize in publishing important books and ensuring they go nowhere. A lower price and better marketing would have been as much a tribute to Prof. Jensen as the book itself.