“What Happened to Black Lives Matter?”

Darren Sands, BuzzFeed, June 21, 2017

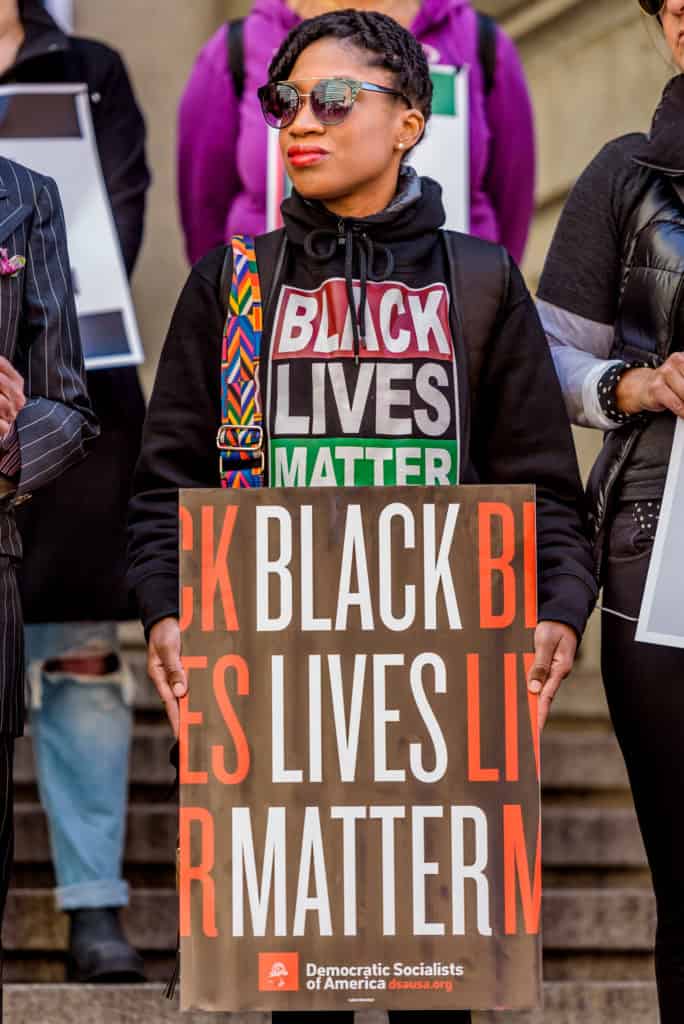

Credit Image: © Erik Mcgregor/Pacific Press via ZUMA Wire

The Highlander Research and Education Center is one of the unsung mileposts of the struggle for civil rights. People like Rosa Parks, John Lewis, and Ralph Abernathy refined their organizing skills at Highlander. It was there, in 1957, that a young Martin Luther King Jr. first heard Pete Seeger sing “We Shall Overcome.” On his way to the airport after the anniversary of what was then known as the Highlander Folk School, King proclaimed, “There’s something about that song that haunts you.” Highlander has since moved farther east, but its mission remains the same.

That’s why shortly after the 2016 election, on November 18, 16 Black Lives Matter leaders selected it as the place to gather.

Top activists in the movement — like Alicia Garza, cofounder of the Black Lives Matter network of organizations (a namesake group), Charlene Carruthers of the Black Youth Project 100, and others — met to privately discuss how to move forward in Trump’s America. (A representative for the Black Lives Matter Global Network disputed that Garza attended the meeting.) Protests had already dominated the news for days. This would be the time for decisive action, undergirded by a clear strategy. Here, in the hills of Tennessee, the activists would come together for a meeting of groups involved in the Movement for Black Lives, an umbrella group of organizations that want the same things, and devise a plan to address the new president, the shock of his election, the law and order he had promised during the campaign, and the devastating blow it all had delivered to generational movements about race and criminal justice policy in the United States. They would devise a plan — like the heroes of the civil rights movement once had decades before.

That good feeling didn’t last long. Few people want to talk about exactly what went wrong — how exactly the meeting devolved. But one problem, according to people who attended or were briefed on the meeting, was pretty simple: The ideas weren’t that good.

{snip}

On top of that — people fumed over this — the meeting had done little to address the structural problems that had dragged down the movement since its meteoric rise from dispersed beginnings to national political influence. Many local activists felt they couldn’t get access to funding, and didn’t know who to take it up with. Organizers felt like they’d been lured in before by the promise of greater collaboration, the sharing of resources, and cultivation of a social community — only to feel left out, especially when it came to the Movement for Black Lives, an umbrella group of organizations that want the same things. Many chafed at the tenet, repeated by the press, that Black Lives Matter was free from hierarchy and instead began to question the existence of tight control exercised by a small group of activists. “The hierarchy was clearer than ever, even though folks are sure there isn’t one on the outside,” said one person briefed on the meeting. For months during the campaign last year, key progressives had watched Black Lives Matter and kept wondering two things many activists on the inside were starting to wonder themselves: What is the movement’s strategy? What is the end goal?

Nobody resolved the structural issues at Highlander. There was no one big plan.

{snip}

Inside the larger movement, many of the movement’s young activists — some of whom had never organized before joining — lack experience in dealing with the realities and challenges of a national effort, and the tricky alliances and factions involved in many political movements. Some have also come up against the hard reality of full-time activism and don’t know what to do.

{snip}

Questions over how unsalaried activists are supposed to lead, oftentimes in a full-time capacity, without a job, has become an unresolved conflict inside the movement.

{snip}

Black Lives Matter is still here. Its groups are still organizing. But Black Lives Matter is on the verge of losing the traction and momentum that sparked a national shift on criminal justice policy.

It’s helpful to describe what “the movement” is in the most basic terms: There’s no way to tell how many people call themselves Black Lives Matter activists in the United States. Activists, largely dispersed across the country but concentrated in some cities or regions more than others, largely communicate online. There is a large coalition of groups called the Movement for Black Lives; some of the activists whose names you might recognize (like Garza) lead that coalition, but others (like Campaign Zero’s DeRay Mckesson, Brittany Packnett, Samuel Sinyangwe, and its army of loyalists) aren’t involved in it. There are no universal meetings. There is no centralized, national organization called Black Lives Matter.

{snip}

In interviews with 36 people inside and allied with the movement — both the optimists and the disillusioned — activists largely agreed that the identity of the movement, its existential purpose and aim, remains unresolved. “If I want to get involved with the NAACP, I feel clear about where they are as an [organization],” said Ashley Yates, a Ferguson, Missouri, protester who has since relocated to the West Coast. “Even if you look at the black Greek letter organizations, they have certain structures so that if something strays too far, there’s something to rein it in. That hasn’t happened with Black Lives Matter or the Movement for Black Lives. It’s not to say it has to happen, but people are unclear about what they are coming to these organizations for.”

{snip}

The broad contours are well known. Black Lives Matter was born sometime after George Zimmerman shot and killed Trayvon Martin in 2012, was charged with murder, and was then acquitted in 2013. Protests started in Florida and in other cities, against how law enforcement handles violence against black people; against mass incarceration, over-criminalization, police militarization; against the way police sometimes commit violence against black people, especially young black men and women. The August 2014 shooting of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old in Missouri, turned those protests into a national cause and obsession.

{snip}

Dozens of organizations sprouted up under the Black Lives Matter banner. Twitter became the staging ground, but these were real protests in real places. In the summer of 2015, the Movement for Black Lives launched a conference on the campus of Cleveland State University.

{snip}

Around then, the debates had begun to intensify about what exactly the movement would do, what it stood for. Different schools sprang up. Some preached a policy-driven approach that would require collaboration with existing power structures, like Mckesson, who started a Washington-style public policy group. Campaign Zero outlined specific policies on a targeted set of criminal justice issues. But unlike the Latino immigration activists who rose to prominence during a similar time period, Black Lives Matter activists faced the challenge of having no particularly obvious target: The US president has immense discretionary power over immigration policy; policing and sentencing laws can vary from state to state, municipality to municipality. Some preached a hyperlocal entry into politics: Activists from the Black Youth Project 100 led the ouster of a state’s attorney in Chicago, Anita Alvarez.

{snip}

Some preached the primacy of demonstration: Only by staying on the outside, only by making people in power uncomfortable through protest, could the movement succeed.

{snip}

As the story goes, three women originated the phrase “black lives matter.”

By her account, Garza wrote a “love letter” to black people in 2013, first coining the phrase Black Lives Matter. Then, Patrisse Cullors put #BlackLivesMatter into a hashtag. Then, Opal Tometi began organizing people online, sensing there was momentum on which the three women could build. Garza has often told this story. (In some corners this narrative has become known, derisively, as the “Founder’s Myth.”) She frames the movement as something that couldn’t be invented.

“It is important to us that we understand that movements are not begun by any one person — that this movement actually was begun in 1619 when black people were brought here in chains and at the bottoms of boats,” she told a Detroit audience last year. “Whether or not you call it Black Lives Matter, whether or not you put a hashtag in front of it, whether or not you call it the Movement for Black Lives, all of that is irrelevant. Because there was resistance before Black Lives Matter, and there will be resistance after Black Lives Matter.” In recent public appearances, she’s said she gave it language — that the movement was a “continuation” of a uniquely American struggle led by black people.

The language and ownership of Black Lives Matter has always been a contentious, fraught subject, and one with significant ramifications. In 2014, Garza grew frustrated as, in the mainstream media, “Black Lives Matter” began to signify the Missouri protests over Michael Brown’s death. A 2016 study — by media scholars Charlton McIlwain, Deen Freelon, and Meredith Clark — examined more than 40 million tweets, finding that #BlackLivesMatter was used only sparingly before August 2014, the same month Brown was killed in Ferguson. This resulted in the media driving the narrative: The Ferguson protests had become synonymous with the phrase Black Lives Matter.

Friends and colleagues say Garza grew fiercely protective of the hashtag — so much so that she moved to make Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives into two separate entities, encouraging others around her to do the same.

{snip}

The Movement for Black Lives is the most prominent group in the larger movement, and many trace its ideology and activism back to Garza. She, more than any other prominent activist, has advocated for staying outside of existing power structures. She, friends say, is not interested in playing ball with Democratic politicians for the sake of a few concessions here and there — or, worse, being used as a photo op prop by politicians. She contends that black organizing has “changed the landscape of what is politically possible” and that people were “no longer content with the same old tactics devoid of a larger strategy that stares transformation directly in the face.”

{snip}

Separatism is hardly a new concept in black political movements — like Marcus Garvey at the start of the 20th century, and even the early Nation of Islam days of Malcolm X, whose activism revolved largely around creating separatist black states, somewhere in the agrarian South. Garza’s growing part of the movement had designs on a society — even if it were a more existential one — free from pain being inflicted on it by police, racist structures, and capitalism.

By intentionally departing from what they viewed as the centralized patriarchal leadership that scuttled other black-led political organizations, Garza and others envisioned a movement in which the most marginalized members of the community took central positions in leadership. This act — of making the most vulnerable the most visible — was part of a broader set of philosophies by which people would govern themselves not only now, but also in preparation for a world in which black people were truly “free.” The world was an abstraction. But it was powered by the idea that three black women (two of whom, Cullors and Garza, identify as queer) had become central to the movement’s image in the public eye.

In response to a critique from outside the movement that the group’s aims were too existential, the Movement for Black Lives in 2015 announced the Policy Table, which produced a policy platform that was wide-ranging and comfortably leftist. They have not abandoned that platform, at least not officially. The Movement for Black Lives has said it’s “focused on a hopeful and inclusive vision of Black joy, safety, and prosperity.”

{snip}

And the group has focused on different policy initiatives: Since the November meeting, the Movement for Black Lives has engaged in an action involving freeing jailed mothers who couldn’t afford bail, and a land-rights campaign. (They’ve also introduced “The Majority,” a coalition of groups that includes United We Dream and progressive grassroots organizations like Color of Change.)

What that all means in practice for the Movement for Black Lives has been a little more complicated. Sometime in 2015, Garza and Opal Tometi — one of the three founders of the Black Lives Matter organization — had a falling out.

An organizer who had come up in the immigration rights movement, Tometi grew up in Phoenix as the daughter of Nigerian immigrants. Friends describe her as an unlikely addition; Cullors and Garza had known each other long before Tometi entered the picture. Today, her group, the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, is carrying out a specific vision: America and the Trump administration, Tometi argued in May, had a “moral obligation” to extend temporary protected status and end deportations to Haiti. The administration has extended the status for 60,000 people for six months.

{snip}

Activists close to the leaders say Tometi has taken a step back from her work with Black Lives Matter. She was not present at the meeting in November in Tennessee.

{snip}

It’s not completely clear why Garza and Tometi split. But according to sources in interviews, as well as what the women themselves have said in public appearances, what is clear is they didn’t agree on the direction of the movement. Garza refused to endorse Hillary Clinton, who once helped promote her husband’s tough-on-crime policies during the 1990s and was unpopular with the economic and progressive left. (Garza’s refusal has attracted the ire of Democrats post-election.) Tometi was having a different experience: Old friends and fellow immigration activists were speaking to her about the black activists showing up for brown people. Friends say Tometi saw a shift toward immigration as a potential pivot for the movement, but one that would take increased discipline. The thought was an extension of Tometi’s feeling that the struggle was a global one; Trump was posing real dangers to undocumented immigrants, and he was wrapping up the nomination.

{snip}

On the outside, though, organizers like Marissa Johnson, a co-founder of the Safety Pin Box who is perhaps best known for interrupting Bernie Sanders before thousands in Seattle, suggested Garza’s protectiveness over the phrase “black lives matter” paid dividends for the group but created challenges for others. In an interview with BuzzFeed News, the former Black Lives Matter Seattle organizer said the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter is what encompasses all the movement’s activity, and therein lies a very particular dilemma. “Part of the problem there is a lot of the resources end up getting directed to just the national [organization] because people on the outside of the movement don’t know any other names besides Black Lives Matter,” Johnson told BuzzFeed News.

{snip}

Activists do have disagreements over where resources should be directed, and how it should be done. Johnson quietly led a campaign during 2016, questioning the allocation of resources. Intra-movement tension spilled over into a meeting that Black Lives Matter leaders held in Charlotte in August of last year. According to one source in attendance, people talked about how well-known, accomplished local leaders had spoken of being homeless, or close to it. “There were at least four people at the national convening talking openly about being [personally] housing insecure,” the source said.

It’s not clear what kind of resources and money truly exist inside the movement. Funding for activism is often difficult; fundraising (even in the age of crowdsourcing) can require intense, dedicated work (meetings, travel, pitches, compromises), tailored to foundations or donors, who operate on their own timetables.

{snip}

After three years in the public eye, Deray Mckesson is still reckoning with what his popularity means (he does not, for instance, think that it offers him a lasting mission for his life).

{snip}

He says his speeches now are part of a larger effort, an attempt to give would-be allies he engages with in live settings “language they can repeat.” It’s not clear how Mckesson sees this as a means to his ultimate goal, which is the creation of a mass movement pushing for changes in criminal justice policy. He does it anyway: He performs, he is an eloquent speaker, and the performative part of it all is a real hit.

His critics inside the movement are numerous, though there are fewer these days. The main complaint about Mckesson has been that it’s always about him. A Bowdoin-educated Teach for America alum, Mckesson came to prominence in the wake of the Ferguson protests. The things that irk some in the movement make him significantly more accessible to those outside it: He is willing to play the politics game. He is good on TV. He is good in a boardroom. He has policy goals. He hosts a podcast (Pod Save The People) on the Crooked Media network and is a darling of the monied, progressive left.

{snip}

Mckesson and Garza are often held up as examples of movement leaders whose differences and disagreement on tactics embody the split within the movement. “DeRay wants to work within political structures and inform the processes,” an activist close to both leaders said. “Alicia has a more transformative framework. There has always been an inside-outside game, but she wants to disrupt all structures as a strategy.”

{snip}

We also live in an era in which an online movement of dispersed activists elevated — and for many Americans, introduced — an entire paradigm for viewing race and policing in the United States.

Black Lives Matter did that. If you think of the conversation, on Twitter or Facebook, on the news, after a shooting, that conversation has changed and intensified in the last decade. Local shootings become national news for a reason now.

The movement’s organizers are still organizing, still trying to figure out what comes next, still trying to keep the momentum alive. Much bigger things could be on the way for Black Lives Matter, or the people who the movement has helped introduce to organizing. But trying to appear united to the outside has put strain on people inside.

Repeatedly, activists interviewed for this story described a culture inside the Black Lives Matter organization that suppresses dissent, or hints of any disagreement that could be considered divisive on the outside. “You do what you’re told,” one activist, who is based in the Mid-Atlantic, told BuzzFeed News. “There’s a tyrannical element.”

{snip}