What Does the Confederate Flag Mean?

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, September 2005

John Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: A History of America’s Most Embattled Emblem, Harvard University Press, 2005, 401 pp.

There is no flag or symbol from American history that stirs such strong partisan emotions as the Confederate battle flag. It would perhaps not be surprising if a symbol of a secession attempt that led to 600,000 deaths still caused strong feelings 140 years later, but the war itself is not what excites passion today. Battlefield sentiment died away quickly, and until the 1950s, both Northerners and Southerners accepted the Confederate flag as a symbol of Southern valor. What makes the flag controversial today is something neither side in the war cared about: the feelings of blacks. John Coski has written a careful and illuminating story of the flag that, in addition to its historical interest, shows how everything in America is interpreted and reinterpreted through the lens of race.

The Early Flags

One of the first acts of the Provisional Congress of the Confederacy was to set up a committee to design a flag for the new nation. At that time, there was still sentimental attachment to the stars and stripes, and the committee produced a red-white-and-blue design modeled on the US flag. It was called the “stars and bars,” and is now known as the first national flag of the Confederacy, but it is not familiar to most Americans.

The better-known flag was proposed to the flag committee by one of its members, William Porcher Miles of South Carolina, but was rejected. One member complained that the diagonal cross looked like a pair of suspenders. Miles had, in fact, at first designed the flag with a vertical, or St. George’s cross, but switched to the diagonal and less Christian-looking St. Andrews cross after complaints from Jews.

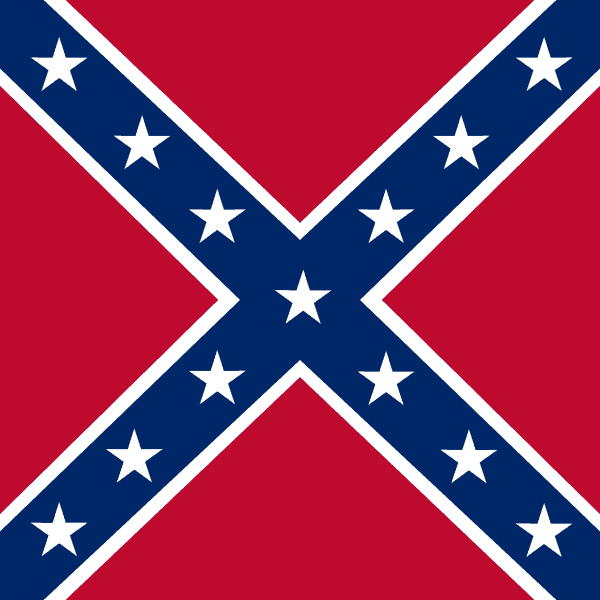

The first national flag was initially very popular with Confederates, but lost some of its appeal at the battle of First Manassas. From a distance, it looked too much like the United States flag, and Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and Joseph Johnston immediately proposed a flag that would not replace the national flag but that would be a distinctive Confederate symbol on the battlefield. They chose the Miles flag for this purpose, and thus was born what is technically known as the Confederate battle flag (many people today mistakenly think this flag is the “stars and bars”). It was adopted officially on November 28, 1861, by the forces that eventually become organized as the Army of Northern Virginia. It became the standard battlefield flag east of the Mississippi, but the Army of Tennessee fought to the end under a variety of distinctive regimental colors. The official battle flag was square, but the Confederate Navy flew a rectangular version known as the naval jack.

The first National Confederate flag.

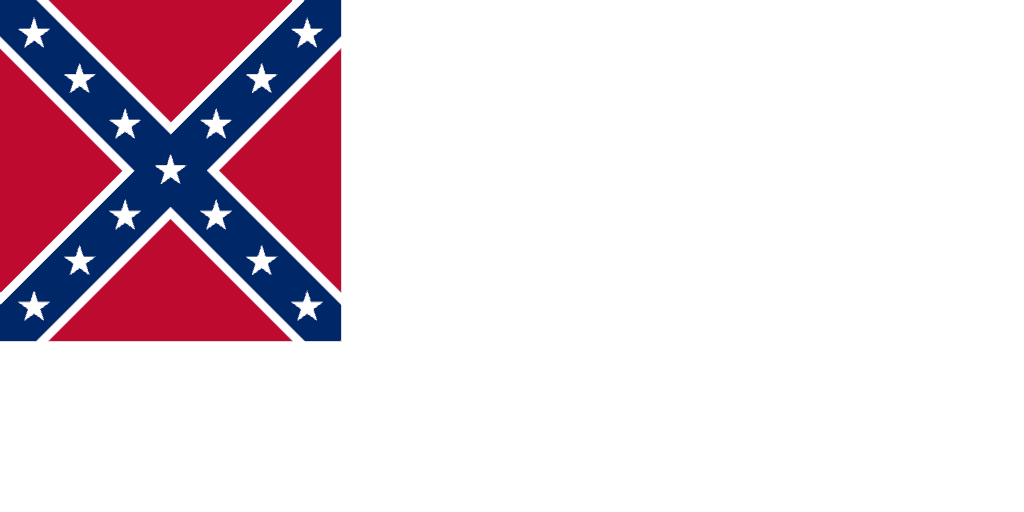

The battle flag was never intended or used as a national flag, and therefore did not fly over buildings. Mr. Coski points out, though, that for a nation that existed for only as long as it could keep armies in the field, the battle flag became its most powerful and best-recognized symbol. Indeed, as time went on and Southerners felt increasingly estranged from the North, the stars and bars fell into disfavor. Commander Matthew Fontaine of the Confederate Navy wrote of his increasing dislike for the national flag. He called it a “servile imitation” of the stars and stripes, to which he was once loyal, but that now stood for “tyranny, cruelty, & oppression.” Sentiments like his prevailed, and on May 1, 1863, the Confederate government adopted a new national flag, known as “the stainless banner,” with a battle flag as the canton on a field of white.

The second National Confederate flag.

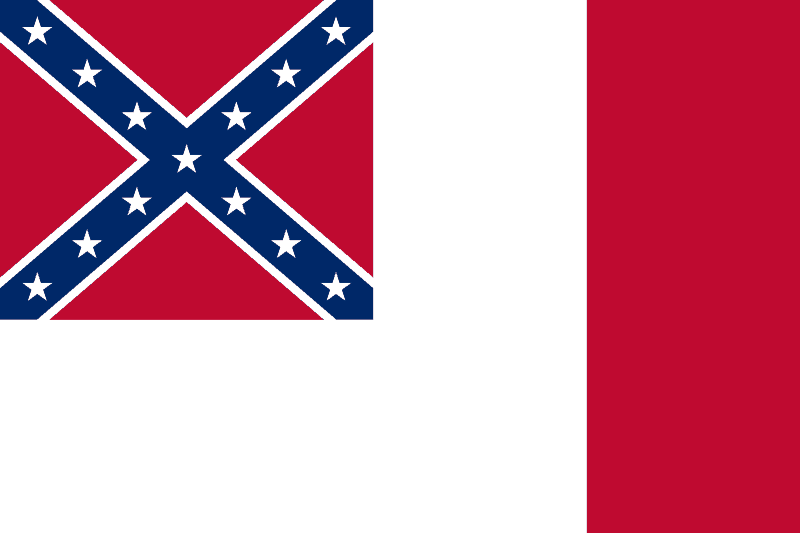

In fact, the flag was all too quickly stained — “very easily soiled from its excessive whiteness,” as one Confederate put it — and when it hung limp on a breezeless day it looked like a flag of truce. Although in the last days of the Confederacy, its leaders might have had better things to do, on March 4, 1865, they adopted a third national flag, which added a bar of red to the “stainless banner.” This was to emphasize an even further departure from “Yankee blue,” and to symbolize the French origins of many Southerners by adopting the red bar of the tricolor. Very few third national flags were ever made or flown.

The third National Confederate flag.

As for the battle flag, it won the devotion of the men who fought under it. Keeping the flag flying, and protecting it from the enemy were paramount goals, and Mr. Coski devotes a chapter to acts of heroism and sacrifice this piece of cloth inspired. It is these tales of heroism that bring tears to the eyes of Southerners who love the flag, and Mr. Coski is right to offer this background for people who think the flag can mean only “racism.”

During Northern occupation, Southerners were under at least implicit orders to keep their flags out of public view, but when Reconstruction ended in 1870 in most states, flags appeared almost immediately at memorial services. Southerners rarely flew or displayed the national flags; the battle flag had already become the Confederate flag.

The flag was very much in evidence at such events as the unveiling of the Jackson and Lee statues on Monument Avenue in Richmond in 1875 and 1890, but US flags reportedly outnumbered Confederate banners. Up until the Second World War, it was common for whatever city that hosted reunions for Confederate veterans — and, later, their descendants — to deck the streets with Confederate and Union flags. Southerners observed the birthdays of Lee and Jeff Davis with much solemnity and celebrated Confederate Memorial Day. It was generally accepted that they could have a kind of dual allegiance that meant no disloyalty to the nation. (Even today, at their meetings, Confederate enthusiasts express this same dual loyalty by both pledging allegiance to the US flag and reciting an oath of devotion to the battle flag.)

In 1898, the North was pleased that Southerners fought courageously in the war against Spain. Joseph Wheeler, who had been a cavalry commander for the South, was in charge of US cavalry in Cuba. There was more amusement than censure when it was reported that he had ordered his men into battle with the words “Boys, give the damn Yankees hell.”

Many Southerners continued to believe and to say openly that the cause of secession was right, and that the Union victory had been a vindication of force, not justice. A few Yankee veterans continued to view the flag as a symbol of treason, but there was much psychological significance in the 1905 vote by Congress to return to the South all the captured battle flags still in federal possession. Most northerners were willing to forgive and even admire Southern loyalties, especially as they did not seem to diminish national loyalty.

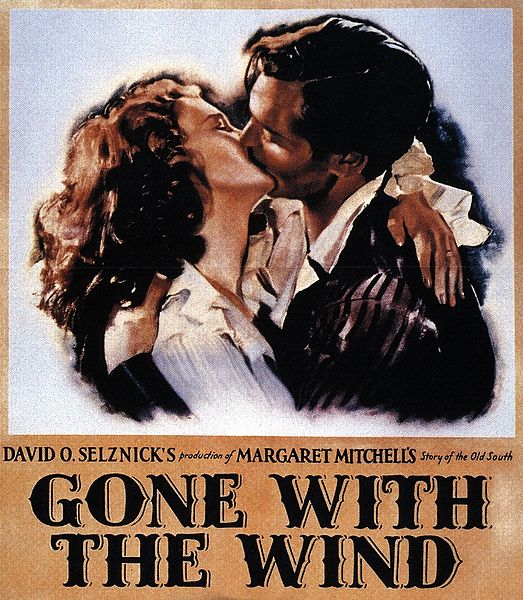

The movie version of Gone With the Wind, released in 1939, was a huge hit, and boosted the South and its symbols. During the Second World War, a considerable number of Southerners carried and displayed small battle flags as talismans, and some even raised them over captured Japanese fortifications. The army was segregated and, if anything, military authorities appreciated the fighting inspiration Southerners drew from the flag.

During this period, the flag was never used as a commercial or political emblem, and had no racial or anti-black connotations. Mr. Coski points out that neither the original KKK of 1866-1871 nor the revived Klan of 1915 used the battle flag. Contrary to later accusations, the flag did not appear at lynchings, nor was it adopted by the more prominent anti-black politicians of the time like “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman.

The Flag Changes its Spots

Mr. Coski is undoubtedly right to argue that the flag lost its innocence, in degrees, after the Second World War. He writes that the battle flag was first put to openly political purposes during Strom Thurmond’s 1948 run for President, as the candidate of the States’ Rights (Dixiecrat) Party. The party stood for limited government and segregation, and although the battle flag was never its official symbol, Thurmond’s supporters waved it enthusiastically, and he never discouraged them. He reportedly marched to the podium to accept the party’s nomination, flanked by both the US and battle flags.

The flag did not immediately take on an exclusively Dixiecrat aroma, however. Mr. Coski reports that that from 1950 to 1952 the entire country went through a battle flag craze that no one seems to have been able to explain. Confederate flags outsold US flags in every part of the country. Shriners on jamborees in New York City waved the flag, and it showed up at the Atlantic City beauty pageant. For the first time it appeared widely on toys, clothes, cups and other items.

The battle flag was also very popular among servicemen in Korea. Americans fought officially under the UN flag, and were happy to rally around an American symbol. Many men who flew the flag and supported its display were not Southern. Southerners teased Northerners that they were finally fighting on the right side: for South Korea.

The 31st Infantry from Fort Jackson, South Carolina, took the flag craze to an extreme. Reactivated for service in Korea, officers wore the battle flag as a shoulder patch and the men put it on their helmets. The band wore Confederate uniforms and had the battle flag on the skin of the bass drum. During this period, a few Navy ships even occasionally flew small battle flags, though the brass discouraged this.

This was the high water mark for the flag, both in the military and the larger society. By 1952 the flag fad had died as mysteriously as it had arisen. After the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education declared segregated schools unconstitutional, the battle flag became increasingly associated with resistance to integration. George Wallace, Lester Maddox, Ross Barnett, and other pro-segregation politicians embraced it. In what has been the source of the flag’s most hard-to-shake association with “racism,” the KKK began to wave it. Although the modern Klan was never large or powerful, it was irresistible to journalists, and hooded cross-burners became, in the public mind, the flag’s biggest supporters.

George Wallace

By the 1960s, Mr. Coski argues, the battle flag had gone full circle and once again symbolized the South’s resistance to Northern attempts to change the racial status quo. As the flag’s anti-black aura increased, the now-integrated military frowned on it. The country was headed towards the large-scale and divisive flag controversies of the latter part of the century.

Because Mr. Coski’s story is about the continuing wars between flag supporters and flag detractors, he is careful to track the historical positions taken by the various sides. He notes that although blacks had little voice in the 1950s, their publications always associated the flag with slavery, not Southern heroism. It is some of the flag’s defenders who have shifted their ground.

The main flag boosters have been the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), the organizations for female and male descendants of Confederate soldiers. The UDC has always been consistent: It opposes any use of the flag other than as a sacred memorial to Southern dead. It was against Mississippi’s decision in 1894 to make the battle flag part of the state flag, and it opposed Georgia’s decision to do the same thing in 1956. It has always denounced commercial use of the flag, whether on clothing or anything else, and officially objected when the Dixiecrat campaign festooned itself with flags.

The SCV took fewer public positions in the period up to the 1960s, but appears to have sided with the UDC in supporting a restrained and dignified role for the flag. In the 1980s and later, it became the most aggressive supporter of the flag, and increasingly took the position that there was no place in the country where the flag did not belong if someone wanted it there (with the possible exception of in the hands of cross-burners), and that any attempt to remove it from view was a “heritage violation.”

Mr. Coski spends many pages on the various battles over the flag. He points out that before the 1970s, playing Yankees and Confederates was as harmless and unpolitical as cowboys and Indians, and many schools, North and South, had teams named “Rebels” and used battle flag symbols. These were invariably all-white schools, and as integration (and its Southern opponents) changed the complexion of the flag, blacks and liberals dethroned the rebels and took away their flags. Given the anti-“racist” zeitgeist, school authorities often felt justified in railroading through changes despite the opposition of a majority of alumni and townspeople. Given the rapidity with which the battle flag has become a symbol of “hate,” it must be a shock for students at northern schools to leaf through a yearbook of 30 years ago and find the football team marching onto the field behind a large Confederate flag.

In many cases, administrators furled the flag even before anyone protested. Mr. Coski notes that Virginia Military Institute, whose traditions had been heavily Confederate ever since the entire student body marched off to fight the Yankees at New Market, started downplaying the flag in 1968, when it first admitted blacks.

More recently, in what have come to be known as “T-shirt cases,” schools have banned displays of the battle flag on clothing, backpacks, or cars. Since the 1980s, these bans have generally been met with lawsuits by heritage groups, many of them successful. However, in some cases courts have found that the battle flag is a “disruptive” symbol, and that schools have the right to ban insignia they think could lead to disorder. Flag supporters are outraged at the assumption that the flag is a provocation, and have sometimes successfully argued that if the Confederate flag is taboo, Malcolm X, clenched fists, and other signs of black power must be banned too.

The campus flag battle that probably attracted the most attention was at the University of Mississippi. For many Southern universities, the battle flag was an all-but-official symbol of athletic teams, especially the football team, but nowhere was it so prominently displayed as at Ole Miss. For games against Northern rivals, the stands would be red with flags, and half-time rituals involved parading a huge battle flag onto the field. The semi-official displays of the flag disappeared under university orders as Ole Miss became sensitized in the 1970s and 1980s like everywhere else, but the fans continued to wave the flag and sing “Dixie.”

In 1997, when the university first started urging people to leave flags at home, the message backfired, and more flags than ever appeared at games. The administration resorted to dishonest tactics, like banning the small flag poles from which the fans waved their flags, on the grounds that the sticks could be used as weapons. With enough pressure and strong-arming, foes of the flag eventually drove it from the stands just as they had from the field.

The flag has now been declared to be so unambiguously offensive on college campuses that there is whooping and bellowing when even a single student displays it. In 1988, a Cornell student hung a flag outside his window. This caused such hysteria the school passed a ban on all flags. In 1991, Bridget Kerrigan hung a battle flag from the window of her dorm room at Harvard. The huge stink resulted in much pressure on Miss Kerrigan but she never backed down. “If they talk about diversity, they’re gonna get it,” she explained. “If they talk about tolerance they better be ready to have it.” Black students hung a swastika from a window in protest, but Jewish groups persuaded them to take it down. Harvard considered banning all flags, but never did. Miss Kerrigan kept her flag to the end.

In 1987, the NAACP concentrated its fire on four specific battle flags: the ones that appeared on the Georgia and Mississippi state flags and those that flew over the South Carolina and Alabama state houses. Mr. Coski gives good summaries of the thrust and parry that eventually led to NAACP victory or at least compromise in three out of four cases, but points out that if the decisions had been put to popular vote, all four flags would have remained untouched. An informal newspaper poll on the Georgia flag — which went through two revisions before finally taking its present form — found that 75 percent of respondents wanted to keep the original battle-flag design, and that the response to the poll was ten times higher than to any question the paper had ever before put to readers before.

This is a typical response, at least in the South, whenever the public is actually consulted about the flag. In Mississippi, the issue was put to put to popular vote and the battle flag carried the day with ease. Black activists were chagrinned that even some majority-black counties voted to keep the old flag.

Mr. Coski notes that every court challenge to these flags failed. Judges sometimes laced their decisions with gratuitous complaints about the symbolism of the flag, but invariably ruled that no one’s rights were unconstitutionally denied just because an official body chose a design or a display that someone doesn’t like.

Still, flag-haters have unquestionably had their way far more often than not. Usually, whites have simply capitulated. The Kappa Alpha Order, a fraternity founded in 1865 at Washington College is a particularly sad example. Founded at a time when Robert E. Lee was president — the school later renamed itself Washington and Lee — Kappa Alpha was essentially a Confederate memorial society, dedicated to emulating the personal qualities of General Lee. Throughout the South, its chapters became known for elaborate Confederate parades, Old South balls, symbolic secession ceremonies, and public devotion to the flag. Over the years, as criticism mounted, one chapter after another ended its public Confederate observances, and in 2001, in what can only be seen as a form of institutional suicide, the order voted officially to end even private display of the flag. On most campuses, there was no university ordinance that required that they turn their back on their raison d’être. The order buckled under pressure.

Mr. Coski recounts many similar stories of battle flags disappearing when its supporters lost their nerve. One of the better known cases was that of NASCAR racing, which had always had southern roots, and a tradition of waving the flag. The sport’s organizers did as organizers almost always do, and banned the flag, in 1993.

As Mr. Coski notes, the battle flag now has an international reputation as a symbol of defiance and resistance to authority. The flag appeared in Solidarity demonstrations in Poland and in marches against Soviet power in the late 1980s. No one had any doubt about what it meant.

What Role for the Flag?

Mr. Coski goes to considerable lengths to claim neutrality in the flag debate. “I do not believe that anyone’s hurt feelings or people’s desire to feel good about themselves should be the basis of how we perceive history or decide public policy,” he writes at one point. And yet, he sets out a logic of flag symbolism that puts him firmly on the side of those who want to see as little of it as possible:

The flag’s effectiveness as an expression of an ideological tradition subverts its legitimacy as a publicly sanctioned or sponsored symbol. If even a minority of vocal flag loyalists regards the flag not merely as a memorial to Confederate dead but as a living testament to the power of anti-federal ideology or the symbol of a still-living Confederacy, it is difficult to defend the flag as a neutral, apolitical symbol that everyone should learn to respect.

He believes the flag should not have the slightest public support unless it is merely a historical relic of a dead past. Some flag defenders implicitly agree with that position by trying to argue that they support it only in that guise, but Mr. Coski is right to suspect disingenuousness. Many of the flag’s strongest defenders unquestionably see a contemporary political meaning in it, and there is more than the “anti-federal ideology” that Mr. Coski suggests.

When Mississipians voted to keep the Confederate symbol as part of the state flag, it undoubtedly reflected reverence for ancestors, but it also reflected years of pent-up anger against blacks and their liberal allies. Whites are tired of watching their leaders give in to every demand by blacks, and almost never have a chance to show how angry they are. A vote on the flag was the equivalent of the vote they never got on racial preferences, the King holiday, and Black History Month. If Yankees didn’t mind the flag, what business did blacks have grousing about it?

At the same time, every group in the country, from blacks to Hispanics to homosexuals, flaunts its identity in the face of the larger society, often with the deliberate intention of giving offense. Only whites are forbidden a group identity, and only for whites are expressions of racial pride treated as moral defects.

Every publicly-articulated assumption about race is a standing insult to whites: They slaughtered Indians, enslaved blacks, interned Asians, stole land from Mexicans. Whites who would never in public dare say they are sick of being bullied and berated are still happy to vote in the privacy of the voting booth or in the anonymity of a newspaper poll to keep a flag flying that they know offends blacks and liberals. That is part of its appeal. It is one of the very few ways to blow a raspberry at the entire liberal-minority enterprise without being thrown immediately into outer darkness.

Whites must hide subversive sentiment behind a still-barely-acceptable attachment to The Lost Cause, because it is too dangerous to attack racial orthodoxy head-on. Most of the people who wave the flag are Southerners, but that is not all they have in common. For one, they certainly do not have the apologetic view of race now required of whites. They probably oppose the entire liberal program, nearly every part of which would be reversed if the people were actually consulted: gun control, mass immigration, welfare, homosexual marriage, and the elimination of public expressions of Christianity. Increasingly, the flag stands for a rejection of an entire world view, and everyone knows it.

That, of course, is why blacks and their allies want to stamp out every trace of the Confederacy. Mr. Coski is right: The flag and the war are potent symbols of an older American racial and political consciousness that has not been quite wiped out, and that shows signs of digging in for another fight. If it were a matter only of tax rates and federal power, the flag might still be the innocent banner it was in the 1950s, but the symbolism of the flag is now unmistakably racial. That is why so many people hate it and why, even if they may feel compelled to hide their reasons, so many people love it.

The fight over the flag symbolizes the larger racial drama being played out in the United States. Just like the students of Ole Miss, and the people of Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama, whites are constantly being betrayed by rulers who would rather sacrifice race and culture than endure liberal censure. The Sons of Confederate Veterans, the Council of Conservative Citizens, and other heritage groups are therefore right to defend flag displays that earlier Confederate loyalists might have found commercial or undignified. These groups are certainly defending their ancestors but they are defending something much larger, something undeceived whites on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line understand and support.